Albion-Little River parcel tax for fire services may be reduced from $600 to $400 after committee listened to residents, discussed and revised

An informal committee of elders from Albion and Little River has now proposed a $400 annual property tax to support the local fire department. This ia a HUGE change from the initial $600 amount proposed. The amount is actually $200 per parcel, but any parcel with a residence gets taxed at $400. The previous tax was $75 and $150, so the increase is still dramatic, from $150 total to $400 for most people.

“Our vote settled us on $200/unit + 2% increase (instead of the proposed $300),” said Committee Chair Tom Wodetzki after the meeting. The next step is to finalize the measure and turn it into the county. The measure wil be turned into the county before the end of the month and then it will be time to gather signatures.

“We think 140 signatures will needed, so we’ll aim for 200. Should be no problem.” Wodetzki said.

Mendocino County’s head of elections, Katrina Bartolomie, said 10 percent of the registered voters, or about 134 signatures are needed. She said the committee has not yet filed a notice of intent or anything else The committee would have up until 88 days before the election to put something on the ballot for Nov 2026

This move to reduce the amount came at a Tuesday night meeting when the organizers had a meeting where ferocious, but polite and friendly headbutting went on among a dozen people. Mendocinocoast.news was there, but we promised not to put anything on the record and we left before the end, so they could argue and iron everything out without the press being there. Their next meeting is Dec. 4 with intent to use that meeting to begin deciding how to go forward. There are no more meetings planned before then so the number is final But since nothing is final until actually filed with the county, we used the word “may” in the headline.

The current proposal closely mirrors 2024’s Measure S, which failed to reach the required two-thirds majority on the November ballot. Measure S proposed a $600 annual tax per residential parcel (land plus home), with a 2% annual increase. Commercial parcels were assessed differently—and notably, some were left out entirely. Organizers say this time, commercial properties will be included.

Measure S received 57% approval—587 yes votes to 437 no—but fell short of the supermajority threshold. Had it passed, it was projected to generate $668,000 annually for the fire district. It’s not yet clear how much revenue the new plan would bring in at the lower rate of $200.

A two-thirds vote requirement for ALL California parcel taxes was established by Proposition 13 in 1978 and applies to taxes imposed by local governments. However, a 2021 appellate court ruling determined that this requirement does not apply to parcel taxes that are placed on the ballot by a citizen initiative, which now only requires a simple majority to pass. THAT is what the committee is going forward with. They will need only the simple majority for it to pass. Bartolomie said she couldn’t say for sure anything about the plan because the county has yet to see any paperwork. She said such questions might require the county counsel to review the paperwork. Because the committee has started so early, it would actually have the time to start over and do it again if there were problems. Recently, an effort to recall the DA failed because of paperwork errors. Bartolomie said she and her staff cannot give legal advice to such efforts, but can only show them the materials needed to do correct filings, which are found on the county website.

Over the course of now five recent meetings, residents dug into the details—how passing an increase in the tax could ease the burden on overworked fire staff, replace aging equipment, and potentially lower fire insurance rates.

Those conversations led to the meeting we attended on Tuesday, November 4—Election Day. There, the committee took a hard, serious look at all the public input.

Every public agency says they listen. Rarely is it true.

But with this group, they treated the words of the public like Gospel.

At the start of the meeting, I asked: Is this a public meeting?

I’d been invited, but it wasn’t clear whether the gathering was open to the public. The committee had been thinking about it, but hadn’t decided. I told them—gently—that openness is always wise when the topic concerns the public. Just my advice, offered to anyone doing civic work.

We told them that MendocinoCoast.news would treat this as not a public meeting. We wouldn’t quote anything said in the room. We noted we might quote something Frank said, but that was it.

So we won’t say what we heard.

But I will say this: it was one of the best examples of public—or non-public—deliberation I’ve ever witnessed. No kidding. The honesty, the diligence, the care—especially on election day—touched me deeply.

these communities risk being divided and isolated. Fire services will be more crucial than ever.

We support future parcel taxes—there, and in our own backyard, if needed.

Everyone was “frank” but me—literally. I was a guest, so I mostly listened.

The debate was vigorous, and no one pulled punches. To witness this kind of democratic process in motion was a thrill.

By my count, there were 14 people in the room, including myself and one other guest—a fireman invited not for his hose work, but for his number-crunching talent.

I can say this much: if you spoke at any of the four previous meetings, your words were taken seriously. If you wrote to the committee, called them, or Zoomed into the Woods meeting, they listened—and they discussed. Every voice was carried into the room.

The result? Shockingly thoughtful. Thorough to the bone. Especially rare in our attention-deficit-plagued 2025.

What we told them—well, what I told them—was this: they should’ve done a survey and had the fireman crunch numbers last summer. As it stands, they’re flying blind.

(And yes, remember I said I’d quote me. Nobody else.)

If a survey had been done, we’d have a clearer picture—what Albion residents can afford, and what the fire department truly needs.

We shared what we’ve heard over years of rambles through the district with the dogs, and 25 years of knowing folks up there. One department-related person hated my idea: that if there are three paid firefighters, they might be assigned to other tasks during off time. But half a dozen residents thought it was a terrific idea.

Sometimes the best data walks on four legs and comes with decades of listening.

We advocated for the $600, as we would pay that on our own property if the stakes were as high as in Albion. And we said add two firefighters, and task them with disaster planing and drills and looking into the water issue. My Albion fire contact doesn’t think that’s what firefighters are for.

This is now moot, under a $200 tax. But we think all departments should be moving to more professional services and a broader role for the more professional firefighters.

We hink it’s time we move beyond old framing. The world needs to invest more—financially and structurally—in professional fire services. That means expanding their role to meet the realities we face now.

And let’s be honest: they do have lots of downtime. Let’s use it wisely.

Take county disaster planning. Wow—could we ever use the help of our firefighters here.

Imagine a cohesive plan for every district. Real drills. Clear evacuation routes. Residents who actually know the risks.

Take county disaster planning. There’s real room for improvement—and our firefighters could play a vital role.

Imagine a cohesive plan for every district. Real drills. Clear evacuation routes. Residents who actually know the risks.

Right now, the county handles it. But let’s just say: it’s not working as well as it could.

For example: the county paid a fortune to a guy named Brentt—yes, with extra T’s—who was billed as a global master of evacuation plans. He’d evacuated parts of the Middle East, or something like that.

He wasn’t much interested in talking to the press about his gold-plated plans. We tried. Supposedly, everyone who needed to know was in the loop.

Sorry, Brenttttt—I’m a person who needs to know.

Brentttttt thought it was no trouble for folks on the Coast to just run over to Ukiah during a disaster. He produced a mountain of PDFs—those may or may not be online at this moment—which few people soldiered through. Then he left for more lucrative pastures.

This is the pattern with Mendocino County.

Hire a guy for a quarter million a year with supposed superpowers.

Then stand back—baffled by his magic.

Then he leaves.

And we start over. Again

How many people feel truly confident about what they’d do if a big fire hit—like the fire that took Paradise, or if the Mendo Complex came roaring back?

I have no earthly idea.

Thanks, Brenttttt. I guess I don’t really need to know.

But if you do—please, enlighten me. So we can tell others.

Okay, enough of the fool’s game of decoding county disaster planning.

Let’s talk about Albion–Little River: its tremendous assets—and its very real challenges

Right now, Albion has a remarkable group of young people volunteering—and that’s a huge asset. One that could easily be lost.

If the district loses this crew, they may never find another like it. There are no jobs, and not enough decent housing to attract new recruits. You might find them in Ukiah or Fort Bragg—but maybe not out here on the Deep End and its scattered environs.

It’s a gift that these folks are here.

But losing them? That’s more frightening in Albion than almost anywhere else.

Locally knowledgeable firefighters are needed here more than in most places.

A bad wildfire could hit Albion–Little River, and there aren’t many ways in or out—especially for folks living on any of the three ridges. In theory, the local volunteer department isn’t the tip of the spear in a massive wildfire response. But that theory falls apart in this magical, tangled place.

Cal Fire can send their best, but they’ll get lost. Good luck with Google Maps—even with a satellite phone. These backroads are weird: bizarre driveways, eccentric residents (whom I love), and terrain that defies navigation. It’s a tough place to drive, and a terrifying place to face fire.

You need local professionals and volunteers. This place is scarier than anywhere else on the Coast—except maybe Brooktrails—because of the dense forests and the access issues. Big challenges, big trees, and big ingress/egress problems. And it’s not a place you can show up to for the first time in the middle of a disaster.

Driving around recently, I popped into places where someone I used to know lived—hoping the new gal who moved in after my old friend passed (without telling me) isn’t afraid of Sasquatch. I ended up down on the Albion Flats, south side of the bridge. Coming back up, the sun was blinding, right over the road. Almost back to the Albikon store, the road turned super steep—nothing but gravel—and I was completely blinded. No more than a foot on either side of my little Honda CRV. It’s got good tires and four-wheel drive, but I was stuck. I had to open the door and look at the ground—under the door—to see if anyone was coming down the grade. I inched forward, tires spinning, skidding sideways twice. I escaped.

But imagine that in a hurried evacuation.

Navarro, Little River, and Albion have a lot of roads like this—narrow, poorly graveled, steep. Yikes. Addresses don’t follow any sequence. Road signs are exotic when they exist—and they usually don’t.

That said, there’s a tendency around here to get a little pedestrian about who “belongs.”

What happens with tax dollars is everybody’s business.

I had people ask if I lived in the district—knowing full well I’m a journalist who’s been around longer than many of them. My address doesn’t factor in when I’m reporting. Tax money affects all of us. Nobody owns public buildings or departments. It’s not a private club.

Everything done by fire personnel is part of a larger American system. The Sheriff’s Department is paid by all of us—and one doesn’t work without the other.

We could use a civics refresher—across the board.

Benjamin Franklin didn’t just found the first volunteer fire department—he helped shape the idea of community-powered public service. The Union Fire Company, established on December 7, 1736, was nicknamed the “Bucket Brigade.” Its members brought their own gear: leather buckets, linen bags, and a shared sense of duty to protect lives and property.

Franklin knew that a free press and a prepared public were essential to a thriving democracy. He was both a newspaperman and a volunteer firefighter. These are grand American ideas—rooted in mutual aid, transparency, and local empowerment.

And the best government only works when it can be examined—critically, openly, and often.

We told the citizens group: once you decide on a tax rate and put it on the ballot, we’re happy to help communicate what’s needed.

We could make a film—showing young firefighters in action, walking folks through the realities on the ground. Someone could demo the equipment, explain what it does. We could show the roads, the challenges, and the reports that highlight Albion’s growing fire risks.

We know Chief Rees has worked on evacuation plans. Let’s show those—and show what still needs to be done to make this a place where people know what to do in a disaster.

The district and fire department were open last time—they held an open house and coffee with the chief. But to succeed today, they’ll need to go further. Full transparency is key. And in this case, the more they show, the more people will support them.

Show the lack of jobs, too. Not everyone knows these young and middle-aged volunteers. Let them speak. Let them share their stories and passions. Show the gear. Let Capt. Schwartz explain—on video—how the new engine helps generate revenue, just like he did in our last story.

Show the engine that flunked inspection at the big fire. Show the stations with no bathrooms, no showers for decontamination after toxic exposure. Show where the money has gone.

As far as I can tell, they have nothing to hide. Maximum disclosure won’t just help pass the bond—it’ll help unify the community and move us forward.

We also advised them to include a checkbox—so people can give more than the tax. Believe it or not, some will. While the folks we see on TV may seem like greedsters with no authentic generosity (looking at you, Jeff Bezos), that’s not the reality here.

We get cynical watching the creeps on the news. But our local wealthy folks? They’re better than that. They know their house could burn too.

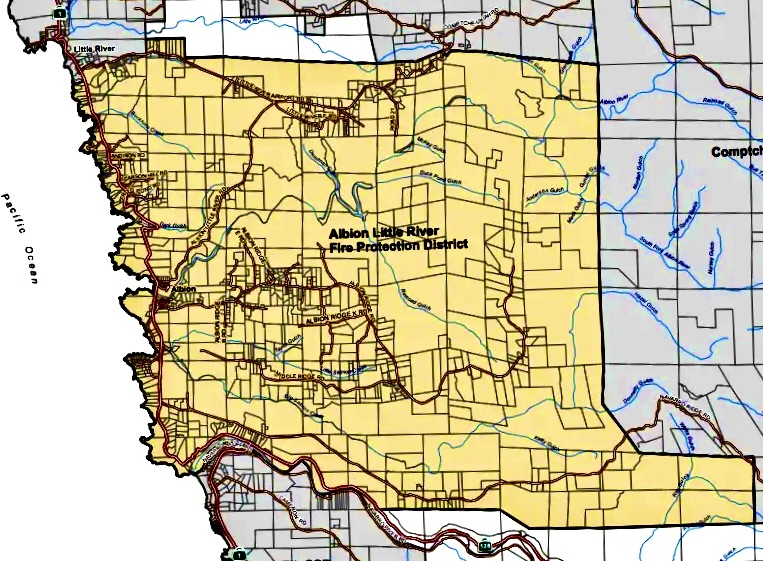

For more, we share our last two stories. We encourage anyone interested to look through the ideas and see if any can help. Although the district includes all of Navarro, all of Albion and about half of Little River, we think of the commnity as Albion. Its easier that way.

If passed, this would be the first fire tax increase since 2014. The Albion–Little River Fire Protection District was formed in 1962, with its board presenting an annual budget for the all-volunteer departments—funded mostly by donations. A $40 tax was approved in 2002 and raised to $75 in 2014, or $150 for those with houses on those parcels.

Albion is still a great community—one that can come together for a vigorous two-hour debate, with coffee in hand and boots still muddy. That kind of civic muscle has been lost in most places I grew up, and seemingly in most places across the country.

But not here.

Here, we still argue like neighbors. We still show up. We still believe that public service is public, and that tax dollars deserve transparency, storytelling, and scrutiny. We still believe that young firefighters deserve to be seen, and that old roads deserve to be mapped with care. We still believe that a good evacuation plan is a form of love.

So value the community. Don’t be afraid to join the argument. It’s not a fight—it’s a fire line. And every voice helps hold it.