Dying giants dance on the Mural – See life size whale from start to finish—a pictorial. But is their hope for either giant?

A slightly-larger-than-life gray whale and a half-sized bull kelp now greet every southbound driver entering Fort Bragg’s heart—boldly splashed across the wall of North Coast Brewing. It’s a visual love letter to our coast: majestic, resilient, and just cheeky enough to make you smile at the stoplight. Add in the redwoods, and we’re practically San Francisco—home of the Giants, minus the traffic and plus the foghorns.

The art carries our hopes the waters off our Coast will once again be full of 40-foot-long gray whales swimming by on their annual migration from Alaska to Baja through towering bull kelp forests. For now, that’s just a wish, a hope. Fewer gray whales than ever are being spotted from the ocean bluffs between Westport and Gualala. The once-reliable migration has thinned, and the underwater forests that fed and sheltered them have withered and disappeared. The mural may show giants dancing, but the real-life choreography is faltering.

Come on a visual journey and story of the science. We start with the first photos of the whale mural, and we’ve chronicled the journey of Fort Bragg’s bigger-than-life gray whale every step of the way. Now, the journey concludes with a coming-out party—where the gender, and perhaps even the name, of our hometown giant may be revealed at Kelp Fest on Oct. 6.

There are two reasons why the whales aren’t showing up like they used to.

1. The kelp. The catastrophic loss of more than 95% of our offshore bull kelp forest beginning in 2014 devastated the entire nearshore ecosystem. Kelp provides shelter and food for everything—from trillions of zooplankton and shoreline bacteria to insects, shorebirds, and lingcod (whose flesh famously turns green from a kelp-rich diet).

When the kelp died, so did the food that once drew gray whales in close for viewing: tiny crustaceans and mollusks that live in the mud beneath the kelp canopy. Gray whales typically dive down, scoop up mouthfuls of mud, and filter out the critters—spitting the mud back out.

No kelp? Then fewer critters in the mud, year after year. The whales had no choice but to go farther offshore in search of alternative food.

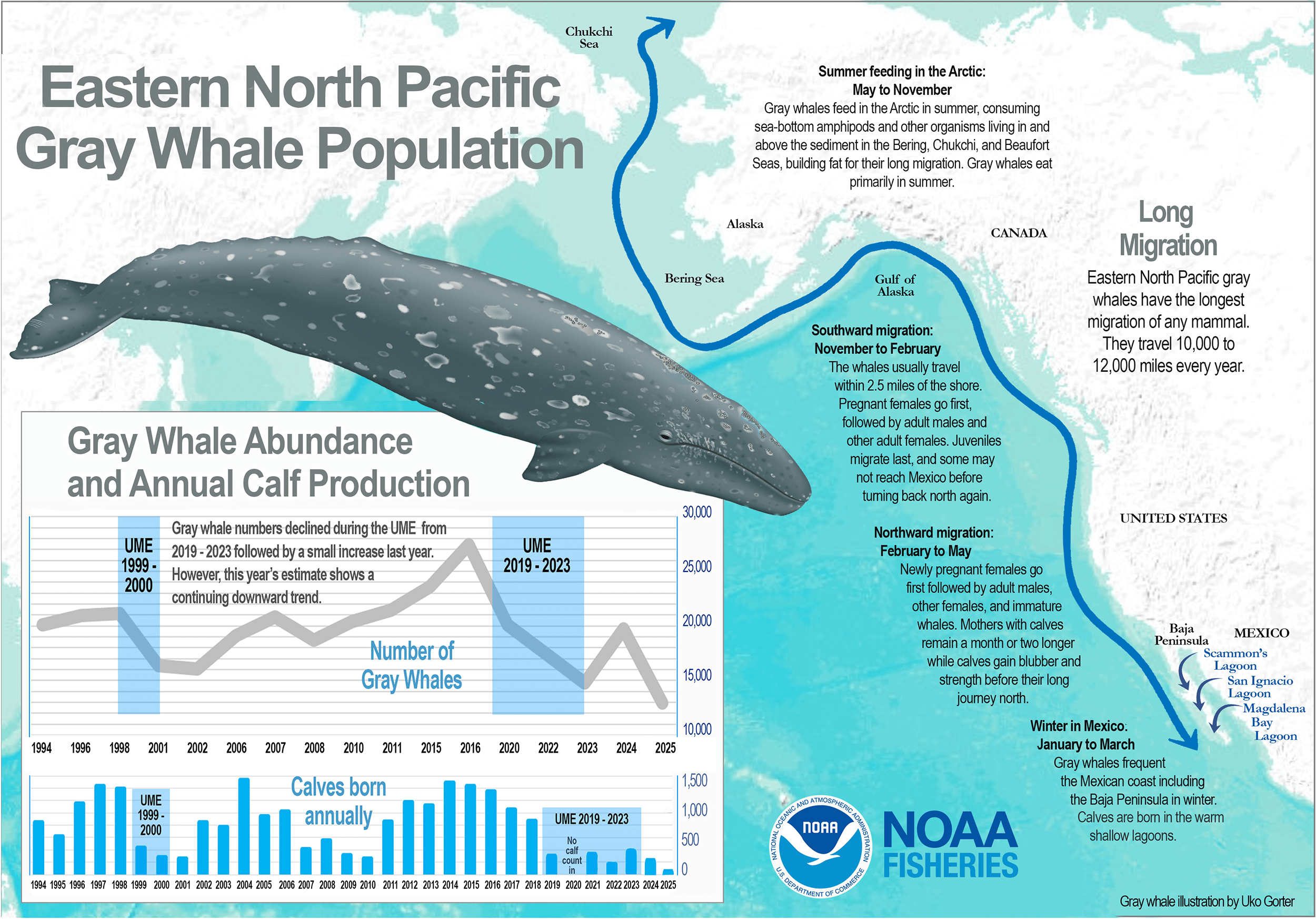

2. There Are Far Fewer Eastern Pacific Gray Whales Today Than Ever Before

The Eastern Pacific gray whale population has been in steep decline since 2019, dropping from 20,500 to just 14,526 by 2023. The 2025 estimate is even more sobering: only 13,000 whales remain—the lowest count since the 1970s, when they were still recovering from commercial whaling. Today, no humans are actively hunting Eastern Pacific grays.

But the whales are struggling. They’re having fewer calves, and many appear underweight or emaciated. Scientists expect an uptick in whales washing ashore dead this year when final numbers are tallied. While whale populations naturally fluctuate, this downward trend is troubling—especially because the causes remain unclear.

One contributing factor is the loss of bull kelp and giant kelp along the coast. These underwater forests are the heart of the nearshore food web. Without kelp, the whales’ feeding grounds collapse. The whales grow thin. They starve. And without enough nourishment, they can’t reproduce.

Warming Arctic waters—where gray whales get most of their food—are also believed to be a major cause of the decline. That food is disappearing. Meanwhile, colder waters in Baja have disrupted breeding and stressed the animals further. Scientists attribute the colder Baja conditions to shifting ocean currents.

Researchers in Mexico reported numerous dead gray whales early in 2025, found in and around coastal lagoons—alongside a strikingly low number of calves. This suggests that many female whales may not be finding enough food in the Arctic to reproduce. The starvation isn’t just thinning their bodies—it’s silencing a generation.

From Cleone’s bluffs to Baja’s birthing grounds, the signs are clear: the giants are struggling. And while our mural shows them dancing, the real choreography is breaking down.

So far in 2025, 47 gray whales have stranded dead along the West Coast—up from 31 in 2024 and 44 in 2023, the final year of the Unusual Mortality Event (UME). While some of the stranded whales appeared skinny or emaciated, others did not. The inconsistency only deepens the mystery. Scientists are still piecing together the causes, but the trend is clear: the giants are in trouble.

There are growing efforts to return the Eastern Pacific gray whale to the endangered species list. It wouldn’t be the first time. Gray whales in the Atlantic were hunted to extinction by men in wooden ships. Across the Pacific in Asia, grays were driven to the edge of extinction. And here—along our own coast—the Eastern Pacific population was on the same path until Mexico, the United States, and Canada stepped in and stopped the killing.

Since 2013, all three of the most commonly seen whales off the Mendocino Coast—humpbacks, blues, and grays—have suffered steep declines. That year, a warm water anomaly known as The Blob hit, unleashing toxicity and triggering widespread species die-offs. It’s now considered the primary culprit behind the collapse of our once-thriving kelp forests.

Gray whales have always been our sentimental favorite. Like clockwork, they arrive every March, en route to Baja to birth their calves. Their migration hugs the coastline in a straight north-south line—predictable, visible, and heartbreakingly vulnerable. That visibility once made them easy targets. Now, it makes their absence impossible to ignore.

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) began enforcing a total ban on commercial gray whale hunting in the late 1940s. Thanks to that protection, Eastern Pacific gray whales rebounded from the edge of extinction to a healthy population. By 1994, they were delisted from the U.S. Endangered Species Act—a rare conservation success story.

But now, that success is slipping. The same gray whales once celebrated as a comeback case are again in crisis. And some researchers are calling for their re-listing, as starvation, low calf counts, and rising strandings threaten the population’s future.

With the steep decline of the Eastern Pacific gray whale population since 2019, some scientists and conservationists are now calling for the species to be relisted as endangered. The numbers are stark: from 20,500 whales in 2019 to just 13,000 estimated in 2025. That’s the lowest count since the 1970s, when commercial whaling had nearly wiped them out.

This time, it’s not harpoons—it’s hunger, habitat loss, and climate disruption. The whales are thinner. They’re having fewer calves. And the food they rely on—from Arctic amphipods to nearshore crustaceans—is vanishing.

Relisting wouldn’t just be symbolic. It could trigger stronger protections, more funding for research, and a renewed international commitment to safeguarding one of the ocean’s most visible giants..

Last Chance for Gray Whales—Help Stop Their Extinction

A traditional gray whale hunt for up to 10 gray whales was approved for a Washington tribe, with hunting beginning in 2025 for 4-5 gray whales.

Tribe Wins Right to Hunt Gray Whales—A Historic Decision on the Washington Coast

…the full kelp forest, the calf, or the dramatic migration arc now visible across the wall.

Larry Foster’s original concept focused on a single gray whale—majestic, solitary, and symbolic. But as the mural grew, so did the story. The kelp came next, then the calf, then the sweeping sense of movement that mirrors the real-life journey from Baja to the Arctic.

What began as one whale became a coastal chronicle. And now, with each brushstroke, the mural reflects not just beauty, but urgency—a visual reminder of what’s at stake for our giants.

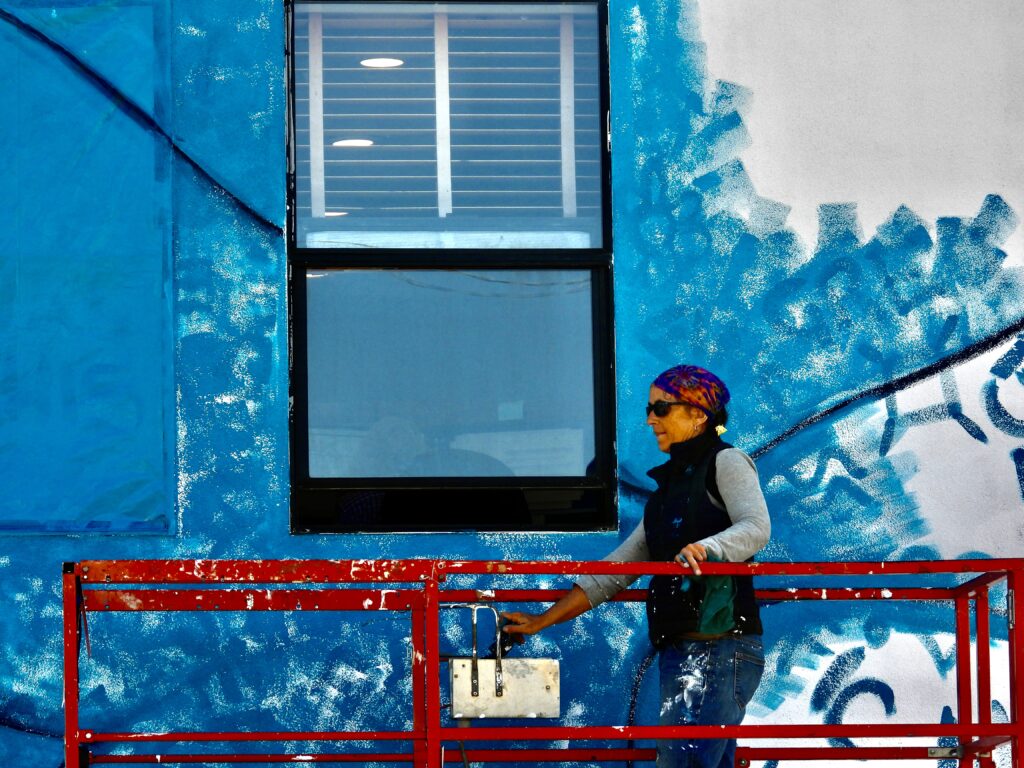

The mural was inspired by a painting from Fort Bragg author and whale artist Larry Foster. But the brushwork belongs to Marta Alonso Canillar of Willits, who became a familiar face to nearly everyone in town as she painted Fort Bragg’s largest mural. The questions, suggestions, and admiration came in waves—so much so that Marta eventually donned headphones just to get the work done.

Foster’s original painting didn’t include kelp. A later mockup added giant kelp, but that species doesn’t actually grow off Mendocino County. Giant kelp have leafy fronds all the way up their stalks, while bull kelp—our local variety—are long tubes with a single tuft at the top. Bull kelp not only reflects the true ecology of our coast, it also makes the mural more visible and dramatic than giant kelp ever could.

Marta Alonso Canillar is determined to give Larry Foster full credit for the art that inspired Fort Bragg’s biggest mural. Foster, a Fort Bragg author and whale artist, is world-renowned for reshaping how whales are portrayed in art. He doesn’t paint blobs or sea monsters—he paints beings with presence, personality, and grace. His love for whales runs deep, and his mission has always been to show them as they truly are: intelligent, expressive, and worthy of reverence.

“I feel like when you mention me in the article maybe it should be slash it as Larry/Marta…or something like that. I am totally respecting his part in all of this and want people to see the art Larry creates…I’m just the executioner…

When Marta Alonso Canillar arrived as the muralist, plans were already in motion to bring Larry Foster’s whale art to life on the wall of North Coast Brewing. A mockup was ready. Then came Lia Morsell—the driving force behind Fort Bragg’s mural revolution—who met with Larry and Marta to refine the vision. It was Lia who suggested swapping out the giant kelp in the design for locally accurate bull kelp, making the mural not only ecologically true to Mendocino County, but a perfect fit for the upcoming Kelp Festival.

Here’s our first story on the mural—one of Mendocinocoast.news’s most popular posts of the summer. It captured the moment the whale first surfaced on the wall, sparked community buzz, and marked the beginning of Fort Bragg’s biggest brushstroke. From Larry Foster’s original vision to Marta Alonso Canillar’s public painting marathon, this was the splash that started it all.

Read the full story and see the mural’s earliest photos:

Thar she blows! What is that sea monster coming out on the walls of North Coast Br\ewing?

Our second story dove deeper—packed with facts, science, and the unfolding crisis behind the mural. From kelp collapse to whale starvation, it traced the real-life struggles of our coastal giants. It also spotlighted the mural’s evolution, the switch from giant to bull kelp, and the community voices shaping Fort Bragg’s biggest brushstroke.

A secret code in suds – Unraveling the hidden message at North Coast Brewery

What’s left to do?

“I’m almost done,” muralist Marta Alonso Canillar said Wednesday morning. “I have to add another kelp ‘tree’ and a couple of enhancements. We’re working on the screens for the windows, and I still have to do a clear coat of varnish… after the unveiling.”

fittings really do?

From Brushstroke to Beacon: The Whale Is Almost Ready

What began as a painting by Fort Bragg’s own Larry Foster—a world-renowned whale artist who refused to paint sea monsters or blobs—has evolved into the largest mural in town. With Marta Alonso Canillar on the wall and Lia Morsell behind the scenes, the whale now swims through a forest of locally accurate bull kelp, its calf close behind, its journey etched in color and care.

This mural is more than art. It’s a living story of ecological truth, community collaboration, and the last chance for a species slipping toward silence. Since 2019, the Eastern Pacific gray whale population has plunged from 20,500 to just 13,000. Calves are scarce. Strandings are rising. The giants are starving.

And yet, here in Fort Bragg, we’ve painted them with reverence—with personality, with movement, with hope.

Marta’s final kelp “tree” is nearly done. The window screens are in progress. The clear coat waits for the unveiling.

So come. Witness the whale. Celebrate the mural. Join the unveiling. Let this be more than a photo op—let it be a promise: that we see them, that we remember them, and that we will fight for their future.

🌀 Unveiling Day is coming. Be there. Bring your questions, your admiration, and your headphones if you must.