Potter Valley Tribe adding, preserving lands in Westport, Caspar

Many California tribes have been buying lots of land – and not for Casinos

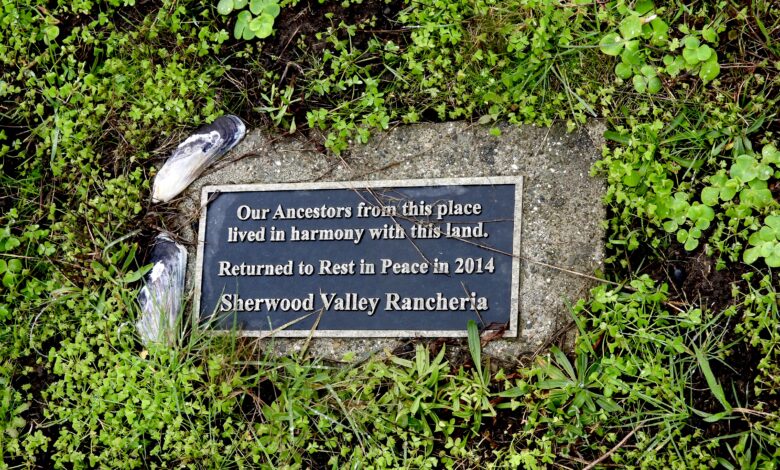

Two markers in the southwest corner of the ocean blufftop Westport Cemetery tell how Native people, once banished in both life and death, recently returned to rest in a favorite spot of their ancestors. “Our ancestors from this place lived in harmony with this land. Returned to rest in peace in 2014 Sherwood Valley Rancheria,” one plaque says. The two markers are tucked together just a few feet from a precipitous drop to the ocean 60 feet below in a cemetery otherwise for setters of a town that ran off all the Natives in favor of a burgeoning lumber town full of saloons and hotels.

Next to that first terse marker is another simple stone plaque, stating that in 2004, unidentified male and female Indigenous persons had been reinternred there. That was a rare Native American display in Westport, which was beloved by many tribes for millennia as a shared foraging spot.

Not anymore.

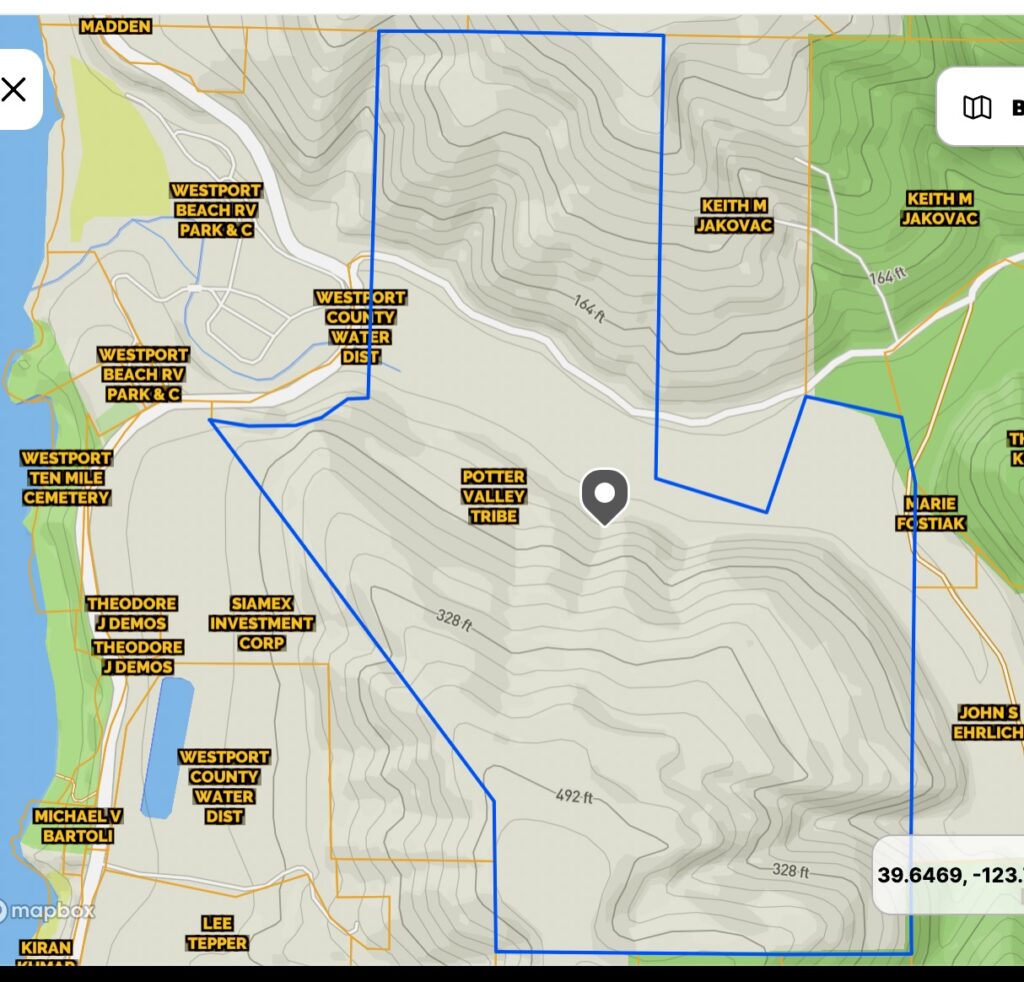

Stand next to those two markers now and look across State Route 1 to 200 acres of newly purchased tribal land. While it is private property, the tribe that bought it plans to use it to expand a successful summer camp program for Native American youth from all tribes and to use it to rekindle traditional practices, as well as for their enjoyment.

The Potter Valley Tribe purchased 200 acres from Lorene Sosa for $800,000, closing the deal on Dec. 16, 2024.

“We’re family people who enjoy camping and outdoor adventure. We have friends that come over to our Pudding Creek property to enjoy all that. We use it for seasonal camping, and the new property in Westport will be just an extension of that and also be another great place for our annual environmental youth camp,” said Potter Valley Tribal Chair Salvador Rosales.

The tribe now has four different significant properties in the works, three on the Coast and one on the Eel River.

A careful reading of land sales shows tribes all over California are buying lots more property, separate from the state and federal governments’ land back movements.

The Potter Valley Tribe’s property near Pudding Creek in Fort Bragg was their first acquisition on the Coast.

Now three more interesting properties have been acquired or are being acquired to enjoy and use in traditional activities like foraging, seaweed gathering, traditional sustainable forestry, and other teachings of ancestral ways.

“We’ve been making use of funding that is out there to purchase ancestral lands. This opportunity is here for now and we don’t know for how long so we are making use of that opportunity,” said Rosales.

The Potter Valley Tribe is one of just 574 recognized tribes in the USA. Many more have tried to become recognized but failed to meet the rigorous criteria. Potter Valley is one of the smaller recognized tribes. The largest is the Navajo Nation, which has 400,000 members.

California has the second largest number of Indigenous people among the 50 states. California natives historically had much fewer people in each tribe and far more tribes than indigenous peoples in the Southwest, Great Plains or on the East Coast.

Some of the larger tribes were recognized by Congress as much as a century ago or established their federal status by having negotiated treaties with the federal government. This became a bigger deal in the 1980s when lots more tribes began building casinos. Then, being in a recognized tribe could be a literal goldmine. Con artists had to be blocked by strict ancestry tests. Even well-known tribes without a recognized burial ground or other required items needed for federal recognition were denied.

The Potter Valley Tribe’s community center is at 2251 S State St in Ukiah. In recent years, the tribe has expanded to include:

• 3.9 acres designated by the Department of Interior in 2016 as the tribe’s lands. (not purchased lands) Later, 5.7 acres on Michael Court in Potter Valley, were added to the tribe’s trust holdings, the property is not continuous to the first property, which is also in the same general area..

• Their first big purchase was the 69 acre Noyo Bida Ranch in Fort Bragg adjacent to Pudding Creek and across from the Beachcomber Motel. They purchased it from a bank in 2018 for $1.65 million. For the previous decade attempts were made to rezone the property and develop it with 255 houses. The city rejected this in the end saying they simply didn’t have water for the project. The city has since greatly increased its water supplies but still has limited supplies. The property had once been home to a Model T Racing track and a destruction derby site. The money came from a fund set up by tribes that have casinos for those who do not have gaming like Potter Valley.

• Next, PG&E donated 879 acres of Eel River Wilderness just north of Potter Valley on the main stem of the Eel River to the tribe., While the property includes old-growth trees, it is also very fragile, having been trashed by more than a century of non-sustainable legacy logging. The tribe was chosen for the donatio partly because of its work on restoration in the area, such as a regular sponsor in the annual Eel River cleanup in the summer.

• Next came the 200-acre ranch above and north of the town of Westport on Wages Creek purchased from the Lorene Sosa at the end of 2024. Youths from a dozen different tribes now use the Potter Valley Tribe’s Pudding Creek property during the annual summer camp and for learning traditional camping, foraging, and other traditional skills. There were 250 participants from 12 different tribes in the summer camp at the peak last year, Rosales said. The newly acquired property in Westport will be used for family camping and to expand the summer campout programs for Indigenous teens. Currently, the summer learners have to go to the Ten Mile River to complete riparian curriculum.

“Now that we have the Wages Creek property they will be able to get into that stream to learn,” Rosales said.

• Finally, the tribe is acquiring a 48-acre parcel just south of Fort Bragg, now in escrow. Rosales said the tribe desires the property for the native plants and mushrooms it comes loaded with, which are beloved by his Potter Valley Tribe family as well as a growing number of us relative newcomers. Rosales said that deal will hopefully close in June.

Westport was a critical place for the Yuki, Pomo and other local Native Americans. The tribes who used Westport also migrated from Coast to inland to feast on summer bounty when the ocean was calm enough to allow it then back to Potter Valley, Sherwood Valley, Coyote Valley and other places. Westport was, and still is a place where the tribes shared the incredible resource of mussels, clams, abalone and seaweed. A kind of festival was held each summer before the Russians and Californians arrived for the making and trading of baskets, including some made of seaweed.

When settlers arrived, they came fast and in violent force against the natives.

In 1881 Westport had two mills on Wages Creek, three hotels, six saloons, two blacksmith shops, three stores, two livery stables, two shoe shops, a barber shop, a butcher shop, a post office and telegraph office, according to newspaper accounts from the day. By 1883 a stagecoach ran between Ukiah and WestporOne account claims Westport had 14 saloons in its heyday. Today the post office survives along with a general store and an upscale restaurant.

But natives continued to return to their beloved foraging grounds, a practice which can still be seen in 2025.

California State Parks found out how valuable Westport beaches still were to Indigenous people when they announced a list of parks facing possible closure to meet budget cuts a decade ago. Although local rangers and park workers knew how heavily used Westport was by indigenous people, the bosses in Sacramento didn’t listen to warnings. They were soon confronted not only by tribal protest but a copy of an agreement State Parks had signed in the 1950s to allow continued indigenous foraging. Parks relented on the closure.

Both indigenous graves at the Westport Cemetery have been decorated recently with mussel and clam shells. The newly acquired Potter Valley Tribe property across the highway is both spectacular and not really suitable for the average hiker. There is a hidden canyon, a hilltop that overlooks the town of Westport and provides 20-mile panoramic views. Wages Creek is currently raging, scouring the heavy underbrush.

The efforts by the federal and state government to return land to tribes is a public process. Millions of acres of land have been returned to tribes, the majority in one deal in Oklahoma. As money has been directed into land back and tribes gain money from casino revenues, many different tribes, not all federally recognized, have been purchasing property all over California in numbers not seen before.

Wholesale murder, cultural genocide and the appropriating of Native lands against California’s Indigenous people began in the 18th century with the Russians engaging in a brutal hunting campaign from the north and the Spanish came from the South creating missions that birthed widespread genocide. But the worst abuses came after gold was found in California and settlers began to squat on tribal hunting grounds. The United States had little patience with the small tribes and force marched them first to the Coast then back to Round Valley and other places, pushing numerous tribes together on places like the Round Valley Indian Reservation. Then to add insult to injury, ranchers weren’t content with their own lands but ran their cattle onto the reservation. They engaged in genocide misnomered as the “Mendocino Indian War.” To the horror of the 19th century California Legislature, Mendocino ranchers told how they had shot Native people on their reservation who took trespassing cows, considering the human beings no different than vermin. The legislature documented that at least 1000 Yuki were murdered in the 1850s during this genocidal campaign, which had support from local law enforcement. In places like Westport, Natives were likely to be raped, captured, enslaved and sold or shot.

The population of Native American California was reduced by 90 percent during the 19th century—from more than 200,000 in the early 19th century to approximately 15,000 at the end of the century, according to Barry Pritzker’s esteemed 2000 reference work, A Native American Encyclopedia. Native Californians who survived were often subjected to forced reeducation, such as sending their children where any native behavior was discouraged and speaking of their languages prohibited.

Rosales wife is a member of the Round Valley Indian Reservation and her great-grandfather was a Coastal Yuki. While there are books and stories from some of the local tribes, others have been lost entirely.

Many natives identify with multiple tribes.

“My kids, that’s where they’ll get their ties. We are reintroducing the idea that their ancestors lived on the coast,” said Rosales.

Rosales said the lands being acquired all over will help indigenous people relearn history hands on.

“Where we’re at today is like, what is the history? We need to get it back. It was more or less taken away from us, our traditions, our language. We get bits and pieces,” he said.

What’s next? Many Native Americans and some tribes officially supported President Trump in the election. Trump has not spoken on the land back movement. Coverage by the native press found both fears and opportunities.

The state is returning 172 acres of Blues Beach and a swath of land to its south to tribes. This one is not a purchase, but won’t be a reservation either. It’s a first creating a tribal non-profit to accept land for all tribe members outside of a reservation or rancheria. All three tribes plan to use the mostly pristine areas south of the beach, loaded with a bounty of mussels, seaweed, fish and aquatic creatures. State Sen Mike McGuire announced the facilitation of that land from Caltrans three years ago. McGwire announces land being returned to tribes Gov. Gavin Newsom signed off on the deal. The land is being given to three tribes working together under the umbrella of the tribal Kai-Poma non-profit but the state has still not completed the deal. There were mistakes in the documents presented by the state, such as the milepost markers cited in the gift not matching the parcels, but nobody has said why the deal has not been completed.

Editor’s note- .after consulting with Native people and others, I decided not to run the photo of the actual gravestone in the Westport Cemetery evocative as the image is. Although it does not name anyone, an unidentified man and woman are buried there. We chose to include the image of the other marker, which is not a grave and seems to have been set up for to announce that Indigenous people were returning to rest in their ancestral home and possibly to keep people away from the older marker. Both photos appear in numerous internet sites without any objection, including the Wikipedia page for the Westport Cemetery. I am hoping to talk to the chair of Sherwood Valley about what led to these two markers and more about the history of Westport.