From Healing to Hosting: The Dingmans Step Into History—Restoring Fort Bragg’s Original Hospital to Shine Once More

Fort Bragg’s Gray Whale Inn Begins a New Chapter

One of Fort Bragg’s iconic historic buildings has found new owners and a fresh future. The Gray Whale Inn, a proud legacy of the Union Lumber Company and a gift to the community, is working toward being able to welcome guests once again.

The new stewards of this beloved structure, where many local residents over the age of 53 were born, are Natalie and Joe Dingman, along with the Dingman family. Their vision: to restore the inn to its former glory, not making any huge changes in honor of the history. Joe, a proud Air Force veteran with both military and civilian service, and Natalie—formerly Natalie Silva, a Fort Bragg High graduate from the early 1990s—are embracing the challenge with enthusiasm.

While the Dingmans won’t be serving breakfast themselves—they’re loyal fans of David’s Deli and other local favorites—they do dream of adding a spa someday. For now, their focus is on the monumental task ahead: restoring a century-old hospital, one beam and brick at a time. It’s hundreds of tons of work, quite literally—and they’re all in.

After closing the deal, the family had a very encouraging meeting with city officials, further fueling their excitement for what’s to come. Fort Bragg’s geometric square treasure, made of irreplaceable old growth redwood and cedar, is soon to shine again.

New Life for the Gray Whale Inn

My wife Linda and I recently stopped by and had the pleasure of meeting Natalie and Joe Dingman, the new owners of the Gray Whale Inn. They’re relocating from Vacaville to take on the restoration of this spectacular and historic property.

Frank Hartzell broke the story earlier this week on KOZT News and Mendocinocoast.news, followed by a great feature from Matt LaFever in SFGATE.

The Dingmans’ enthusiasm is infectious. One of their children is currently attending the Air Force Academy, and the entire family considers this a shared adventure—“We all bought it,” they say proudly on Facebook.

Their plan is to create 10 guest rooms and live on-site. From 1915 to 1971, the building served as Fort Bragg’s hospital, and later transformed into a distinctive inn and community gathering space. Natalie and Joe are captivated by every detail—from the rumored hauntings linked to its hospital days to the exquisite woodwork that gives the building its character and charm.

Natalie and Frank wandered through its spacious halls, the ceilings soaring high above us. We climbed one of the many staircases and followed the steep ramps that once led from the old emergency entrance—either up to the patient rooms or down to surgery. The incline was far too sharp for any modern medical facility, yet somehow, nurses and orderlies had managed to push gurneys and wheelchairs up and down them. It’s always been hard not to envision the nurses in white caps and doctors in their white capes as one walks among the fabulous old wood and wonderfully high ceilings.

“Nurses must’ve had seriously powerful thigh muscles back then,” Natalie remarked with a laugh.

The hospital rose from a community-wide effort, spearheaded by the Union Lumber Company, which provided timber from its nearby mill. They didn’t cut corners—every beam and detail speaks to the craftsmanship and long-gone quality wood of the era. One striking example is the original boiler heater, still standing and slated for restoration by the new owners. It’s a relic of a time when things were built to last.

They don’t make them like that anymore.

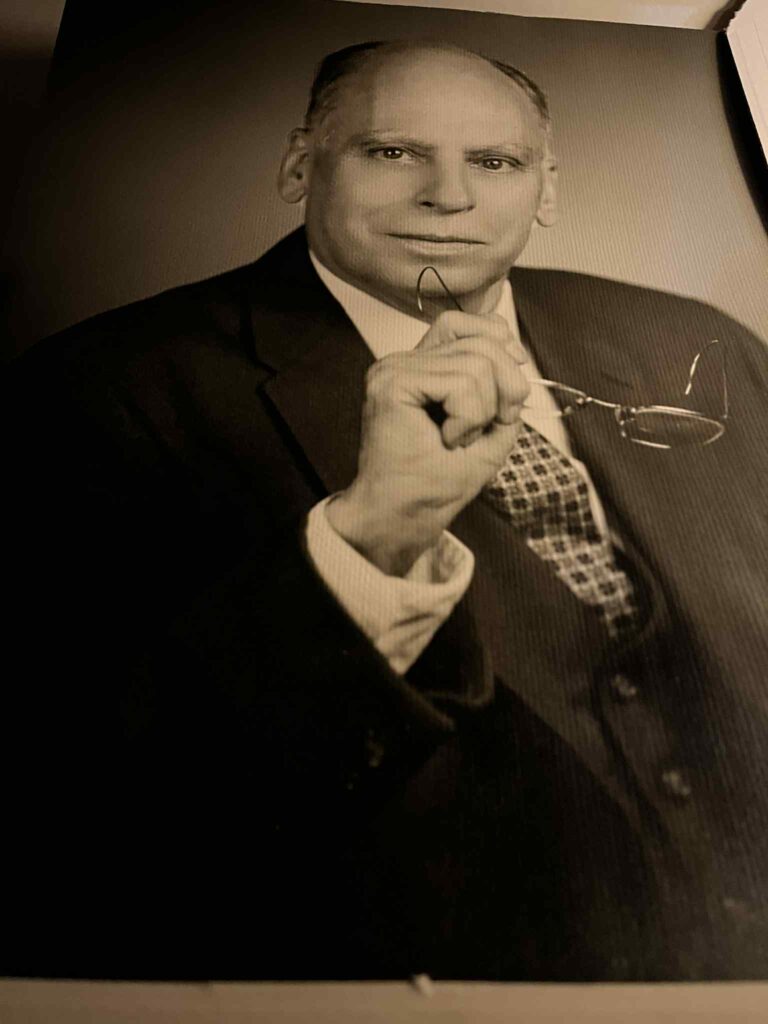

Their daughter Ashley, currently studying at the esteemed Johns Hopkins University, is eager to contribute however she can. Fittingly, that’s the alma mater of the building’s most renowned resident: Dr. Paul Bowman, a towering figure in Fort Bragg’s medical history. He famously declined a lucrative career back East, choosing instead to serve the coastal community he loved. Dr. Bowman remained in Fort Bragg until his passing in 1985, leaving behind a legacy of compassion and dedication.

A Deeper Story Behind the Gray Whale Inn

We wanted to take a moment to share the remarkable story of this building—every bit as grand as the Guest House, yet infused with a deeper sense of purpose. Its walls don’t just echo with history; they hum with the lives once healed within them.

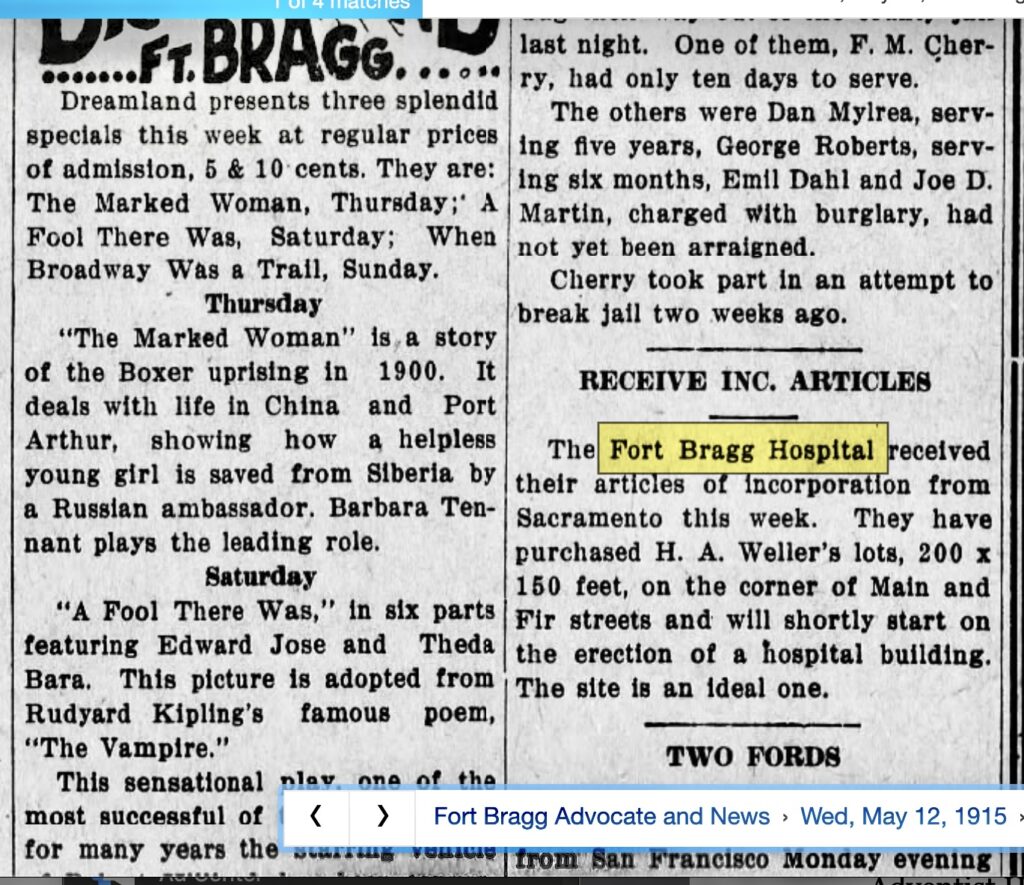

To truly appreciate its legacy, we must journey back to 1915—a time when Fort Bragg faced isolation and urgent need. In response, the community rallied to create the Coast’s first modern hospital. The Union Lumber Company donated the exquisite timber that still shapes the building’s soul, partnering with townspeople to secure the land, raise the walls, and open its doors. It was more than construction—it was a collective act of hope.

This is also the story of the extraordinary Dr. Paul Jay Bowman—a man whose life could easily inspire a Hollywood film. As pivotal to Fort Bragg’s evolution as the founding Johnsons, Dr. Bowman helped transform the town from a remote outpost into a thriving hub for medicine, commerce, and community. He not only led the charge to build the hospital but remained a steadfast presence long after its doors closed, continuing to serve with unwavering dedication.

Before we delve into the story of this magnificent 1915 structure, let’s first visit the quirky, makeshift hospitals that came before it. These humble beginnings set the stage for what would soon become a cornerstone of Fort Bragg’s resilience—a building where care, community, and craftsmanship converged in care and a powerful and involved community.

The earliest hospital we uncovered in Mendocino was the Mendocino Hospital Company, founded in 1887 by Dr. William A. McCornack. It stood at the corner of Ukiah and Howard Streets—still painted hospital white and now home to The Blue Door Inn of Mendocino . This modest facility offered a remarkably forward-thinking model of community care: for just $2 to join and $1 a month, members received treatment, medicine, meals, and nursing during times of illness or injury. It was healthcare built on trust, simplicity, and shared responsibility

The hospital was privately owned by Dr. William McCornack, though early corporate records also list Charles C. Johnson—Fort Bragg’s founder—as a stakeholder, suggesting a broader vision for regional healthcare. That vision quickly took root. The operation expanded north to Fort Bragg, establishing a 33-bed hospital on the site where Mayan Fusion now stands. By 1906, membership had swelled to 700. That same year, following the devastating San Francisco earthquake, McCornack cashed out and relocated to Oakland. He was never seen here again.

History books often portray the oldest hospital as a beacon of progress—a kind of salvation for the Coast. It’s the Chamber of Commerce version: one glowing memory in books after another. But the reality, especially in the years surrounding Dr. McCornack’s departure, was far more complicated and darker. Between 1907 and 1911, real news reporting was going on locally. Read those old papers and a different picture emerges. Articles and hospital advertisements revealed a medical scene that was, at times, more theatrical than trustworthy. Some doctors—including McCornack himself—came across less as healers and more as snake oil salesmen, peddling cures with questionable merit.

It didn’t take long for the cracks in the membership-based care model to show. Fort Bragg Hospital began aggressively promoting patent medicines—many of which were dismissed as “snake oil”—and these fell outside the scope of the membership fee. In some cases, medical care was administered not by trained physicians but by traveling salesmen, blurring the line between healing and commerce. What began as a promise of accessible care often veered into the realm of profit-driven medicine.

By 1913, the community distrust was undeniable. This was the age of science! Advertisements in the Advocate News and Mendocino Beacon pleaded for new members, boldly proclaiming “UNDER NEW MANAGEMENT” in hopes of restoring public trust. But by 1914, the community’s patience had worn thin. The Advocate News reported that many locals were bypassing the hospital entirely, choosing instead to endure the long, arduous journey to San Francisco for reliable medical care. The promise of local healing had faltered—and the town knew it.

This wasn’t merely a shift in geography—it was a quiet rebellion against a system that had betrayed the community’s trust. The pre-1915 hospital may have been born of good intentions, but its legacy is complex: part mutual aid experiment, part marketing ploy, and part cautionary tale about what happens when profit overshadows care

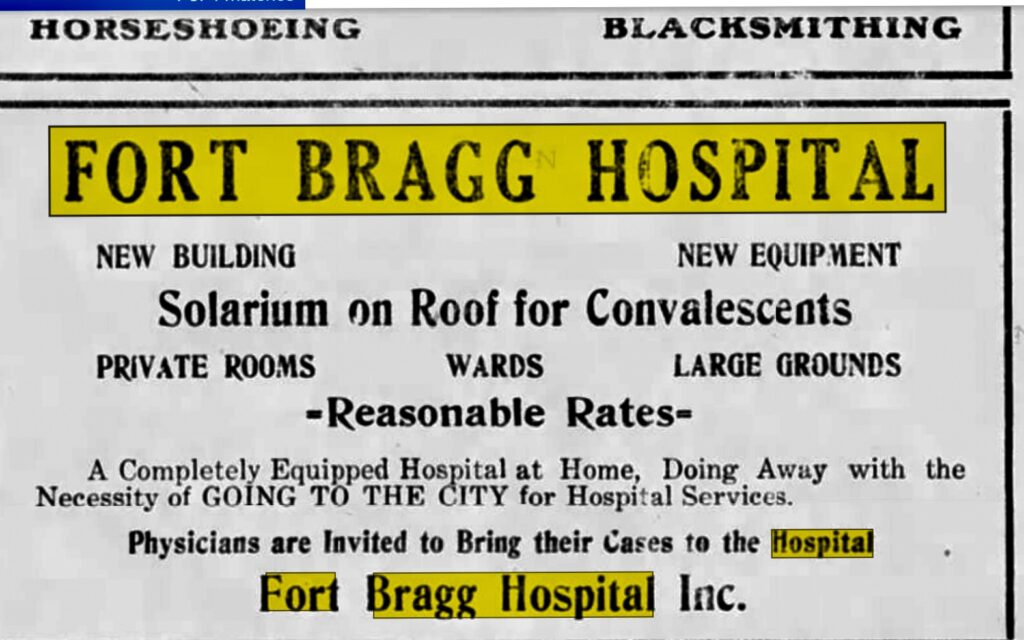

Local business owners and landholders joined forces to recruit physicians to Fort Bragg. Visiting doctors— drawn by the promise of fishing, fresh air, and country living—found common ground with the town’s own medical practitioners. United by frustration over long journeys for proper care and the empty promises of patent medicines, the community rallied to build a true hospital at 615 North Main Street. At last, Fort Bragg had a place where doctors could hang their shingle and serve their neighbors with dignity.

1915: The Dawn of Modern Medicine in Fort Bragg

One could say that modern times in Fort Bragg began in 1915—the year the true hospital opened its doors, staffed by university-trained physicians and outfitted with pristine operating and examination rooms. It marked a dramatic departure from folk remedies and Civil War-era practices, when amputation was often the only answer to infection. This was the dawn of scientific medicine on the Coast—a turning point born of sacrifice, community resolve, and a shared vision for better care. That spirit has sustained Fort Bragg’s hospital for more than 110 years, evolving with each generation while honoring the legacy of those who built it.

Though privately owned, the hospital was undeniably a community endeavor. The Union Lumber Company—guided by a socially minded ethos—supplied the timber and helped raise the structure for the town. The Weller family sold the land at a generous discount, and local business leaders formed a partnership to back Dr. Franklin Campbell. With their support, he launched what swiftly grew into a far larger operation than anyone had imagined. As demand for medical care surged, the hospital became not just a facility, but the beating heart of a town in transition.

Dr. Campbell was doing his best to serve Fort Bragg when fate intervened. A chance encounter in San Francisco introduced him to Dr. Paul Bowman—one of the most influential figures in Fort Bragg’s history and a titan of its medical legacy. A graduate of Johns Hopkins University, then among the most prestigious institutions in the world, Dr. Bowman had been expected to follow his family’s path into elite East Coast medicine. But the Golden West called, and he answered.

In a charming twist of fate, Ashley Dingman—the daughter of the couple who recently purchased the Gray Whale—is currently studying at Johns Hopkins herself. It’s a poetic echo across generations, linking Fort Bragg’s storied past to its promising future.

Drawn by a love of towering trees and the great outdoors, Dr. Paul Bowman longed to work among the redwoods he’d only glimpsed in black-and-white photographs. After graduating, he did his internship in San Francisco, where he crossed paths with Dr. Franklin Campbell at a railroad hospital. Yet despite the city’s opportunities, Bowman hadn’t found his true calling—until Dr. Campbell invited him to temporarily fill in at the Fort Bragg hospital during the Great Flu Epidemic. While Campbell took a much-needed respite, Bowman stepped in—and something clicked, old newspapers show.

An avid forest hiker—unusual for the time—Dr. Bowman quickly fell in love with the region’s rugged beauty as well as a local nurse named Ruby Ingeborg From. When offered a permanent position, he left behind the prestige of East Coast medicine to become Fort Bragg’s family doctor. In 1923, he purchased the hospital from Dr. Campbell and his business partners, renaming it the Redwood Coast Hospital. For Bowman, serving the entire Coast wasn’t just a professional duty—it was a moral calling. He retired the “Fort Bragg” name to reflect a broader mission and to honor one of his favorite plants: the resilient, towering redwood, a symbol of strength and healing rooted in the land he had come to cherish.

Then came a transformative idea. At the time, lumber companies were facing a crisis: few men were willing to work in remote forest camps, where food was unpredictable and medical care nearly nonexistent. Dr. Bowman saw an opportunity—not just to treat illness, but to reshape the region’s relationship with health. He proposed a bold solution: bring medicine to the camps.

What followed was nothing short of revolutionary. Bowman began organizing mobile clinics and dispatching medical teams into the woods, offering care where it was needed most. His efforts didn’t just improve worker health—they boosted morale, stabilized the workforce, and deepened the bond between industry and community. The hospital became more than a building; it became a lifeline stretching deep into the redwoods.

This was the Roaring Twenties—not the Wild West—and the lumber workforce in the woods had nearly vanished. Yet Dr. Paul Bowman found a way to make his newly acquired hospital thrive. He secured a well-paying contract to treat injured workers deep in the forest. Union Lumber would take him to the camp on their speeder, his black medical bag in hand. On the way back, he’d sometimes hike for the thrill of the forest, pausing to admire and study the foliage, merging three passions—forestry, medicine, and hiking—while keeping the community hospital afloat.

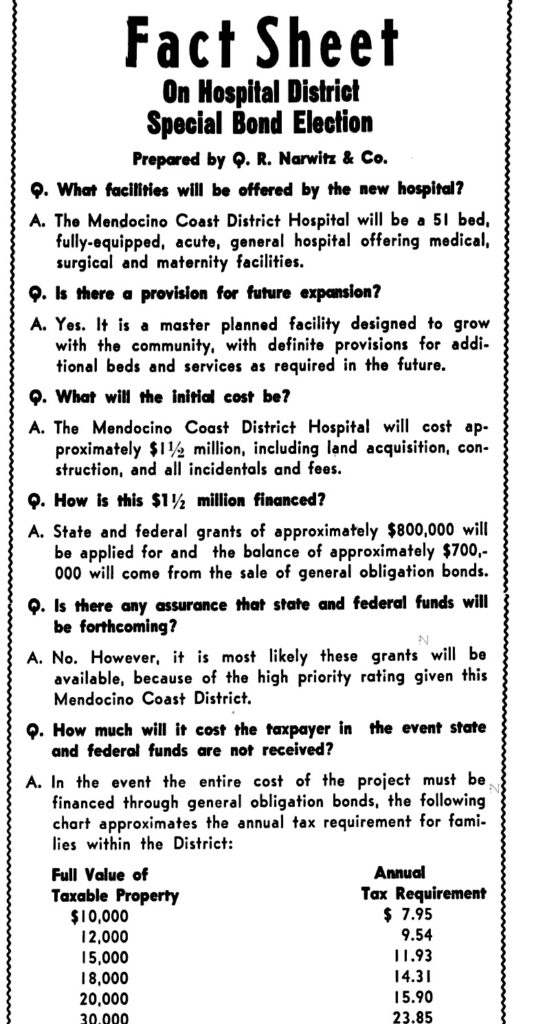

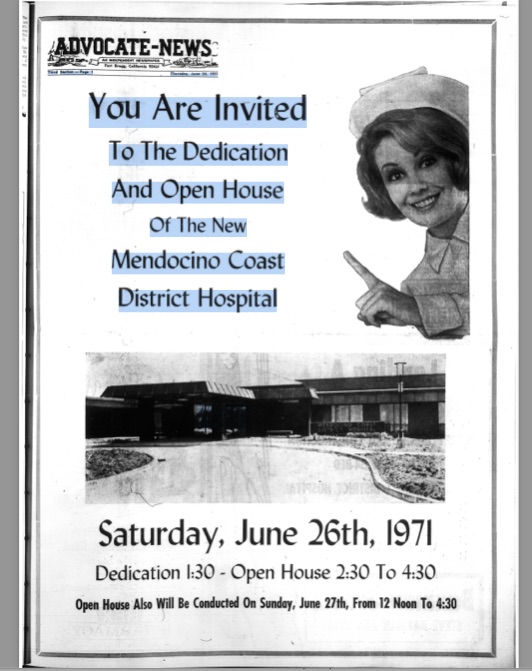

Dr. Bowman ran the hospital from 1923 to 1966, becoming a pillar of Fort Bragg’s medical community. As his retirement loomed, a sense of panic swept through town. What would happen to the hospital without him? Bowman shared that concern—and amplified it. He addressed the newly formed Fort Bragg Rotary Club, urging the town to embrace a truly modern hospital. His old ways, he insisted, couldn’t carry the future any more than those he inherited from Dr. Franklin Campbell.

With characteristic resolve, Bowman helped lead a sweeping campaign to form the Mendocino Coast Hospital District, advocating for a property tax to fund a new facility. The final cost—an astonishing $1.5 million—reflected the scale of the vision. Bowman remained in Fort Bragg as a senior statesman of medicine for decades. After retiring in 1966, he lived on until 1985, passing away at age 91. His well-worn hiking caulk spiked boots now rest at the Guest House Museum.

In a twist the old doctor might have appreciated, he’s remembered as much for his rhododendron breeding as for his medical legacy. He helped spark the local “rhody” phenomenon, adding color and charm to the region he loved. Long before Bowman tired of hiking into the forest, the lumber companies had shuttered the last of their camps—now just memories in places like Camp 20.

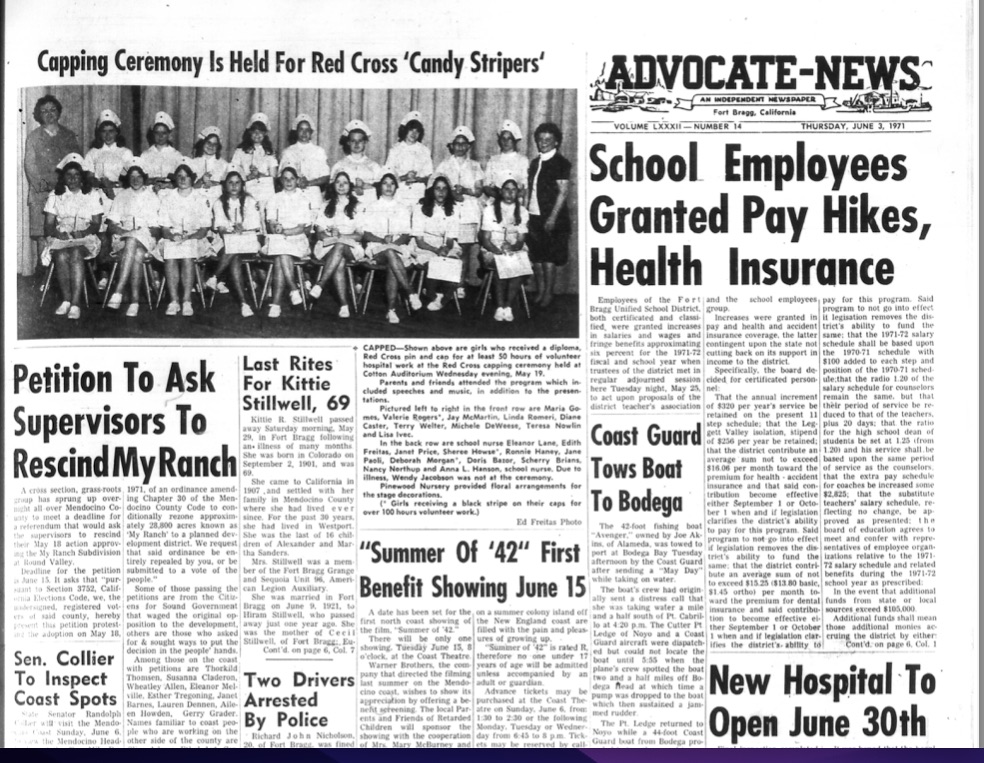

From 1966 to 1971, The Advocate News devoted countless hours to poring over hospital budgets and engaging the community in spirited discussions about long-term needs—looking ahead not just to the next decade, but to distant horizons like 2025. It was a time of deep civic reflection, when journalism served as both watchdog and town hall, helping shape the vision for a hospital that could grow with the community it served.

Public engagement with our hospital has dwindled to a troubling low. When no one showed up—neither in person nor on Zoom—for a meeting the hospital board cryptically labeled an “earthquake retrofit workshop,” it marked a quiet crisis in civic participation. In reality, that meeting involved decisions that will shape our future. The lack of transparency was striking.

Much has been lost over time, most notably The Fort Bragg Advocate News, once a cornerstone of community journalism. It didn’t just report—it led. It publicized, criticized, built consensus, and ultimately celebrated the efforts that mattered. Today, it’s a shadow of its former self, reduced to printing press releases from authorities. The kind of reporting that holds power to account takes hours—days even—to follow, research, and understand. And in 2025, none of our local media outlets (with the notable exception of the Anderson Valley Advertiser) seem wired to do anything but nod along.

Suggesting old-school ideas like advocating against confusion, scams, and sales pitches—or championing worthy community efforts and public records—now feels almost rebellious. Our rivals bristle at the notion. Yet these principles were once central to journalism itself, stretching back to James Franklin, Ben Franklin’s brother, who pioneered the idea that the press should serve the public—not the powerful.

We say: no community news, no community.

No critical voices, no credibility.

When journalism becomes a mouthpiece, democracy loses its pulse.

When meetings go unreported, decisions go unchecked.

And when the public is kept in the dark, the future is written without them.

It’s not nostalgia—it’s necessity. We need watchdogs, not lapdogs.

We need storytellers who ask hard questions, not just echo answers.

We need the kind of journalism that builds bridges, not just headlines.

Because without it, we don’t just lose the news. We lose ourselves.

Reinvention and Resilience: The Hospital’s Evolution

Throughout its history, Fort Bragg’s hospital has continually reinvented itself—driven by the evolving needs and voices of the community it serves. After 1971, the facility entered a new era of modernization, adding a contemporary emergency room, upgraded laboratory spaces, and a welcoming reception area that stretched south and west. Then, in 2011, another milestone was reached with the opening of a state-of-the-art diagnostic center, further solidifying the hospital’s role as a vital hub for coastal healthcare.

The hospital board hoped that the advanced imaging equipment—including cutting-edge X-ray machines, scanners, and nuclear and magnetic diagnostic tools—would generate enough revenue to stabilize cash flow, which had begun slipping into the red. It was a bold investment in the future of local healthcare, driven by the same spirit of innovation and community support that had sustained the hospital for over a century.

But technology alone couldn’t guarantee sustainability. As reimbursements fluctuated and operating costs climbed, the hospital faced new pressures—ones that couldn’t be solved with machines or expansion alone. What had once been a community-driven institution now risked drifting from its roots, unless the public re-engaged with the same urgency and unity that built it in the first place.

It did not. The hospital district declared bankruptcy in 2012, emerging reorganized in 2015.

Then came Adventist in 2020. Voters overwhelmingly approved the transfer—by a 90 percent margin—placing their trust in a new chapter for Fort Bragg’s hospital. The new operators signed on for a 30-year lease, stepping into stewardship with high hopes and broad community support. But fate had other plans. Just as Adventist took the reins, the COVID-19 pandemic swept in, shuttering public life and keeping everyone indoors. The timing couldn’t have been more difficult. What was meant to be a moment of renewal quickly became a test of resilience, transparency, and trust.

A Personal Note from Frank Hartzell

In 2021, I began working for a contractor at the hospital, and the experience has truly changed my world. From the inside, I’ve witnessed Adventist Health make meaningful upgrades to a facility they don’t even own—unlike their site in Ukiah. One standout example: they replaced the aging carpet with modern flooring that our exceptional cleaning crew can keep bacteria-free. That single change helped earn us recognition as one of the cleanest hospitals in California. It’s a testament to what’s possible when care, commitment, and community pride come together—even in a leased building.

While my heart belongs to writing about salmon and pelicans, I want to be absolutely clear: I will never report on any patient, staff member, or internal policy from Adventist Health—or from any other contractor operating at the hospital. I’ve been asked, and I’ve always politely declined. That boundary isn’t just professional—it’s personal. It’s about trust, ethics, and honoring the line between storytelling and confidentiality.

A Call for Transparency and Engagement

As a taxpayer, I’ve often felt frustrated trying to understand where the money is going and who’s making decisions on my behalf. When I ask questions, I’m usually directed to a stack of budget reports—dense, jargon-heavy documents that offer little clarity or accessibility for the average community member. It’s not transparency if no one can understand it. Public oversight shouldn’t require a finance degree. It should be built on plain language, open dialogue, and a shared commitment to accountability.er the clarity or accessibility most community members need.

I’d love to see the hospital hire a public relations firm—just once a year—to host a large public meeting where everything is explained in plain language. No jargon. No buried budget lines. Like the city did with the Skunk Train and millsite issue. Hundreds showed up and that is not important compared to the future of the hospital. We need to work harder at clear communication about what’s happening and why. With so many changes and investments underway, it’s more important than ever for the hospital to communicate like other public agencies do: clearly, consistently, and proactively.

This isn’t about marketing—it’s about respect. Respect for the taxpayers who fund the infrastructure. Respect for the community that built the hospital’s legacy. And respect for the future we’re all trying to shape together.

My wife Linda, one of the driving forces behind Mendocinocoast.news, has taken a deep and thoughtful interest in the future of our hospital. And she’s absolutely right: the direction this institution takes will shape the quality of our lives—and even the value of our properties—more than almost any other factor. Healthcare isn’t just a service; it’s a cornerstone of community stability, economic resilience, and personal well-being. When we invest in transparency, accountability, and long-term planning, we’re not just protecting a building—we’re safeguarding the soul of Fort Bragg.

A Moment of Reckoning at the Hospital Board Workshop

We watched the board make sweeping decisions during what was labeled a “workshop.” I turned to Linda and said I’d never seen a public board operate like that—ten callers from high-priced consultants, a flood of documents released all at once, and then, by the end of the meeting, everything was decided. It felt less like a workshop and more like a done deal.

I walked away at that moment. But Linda stayed. She took it on.

Linda does a lot of the work here that I get credit for, and she’ll be handling this big story from here forward. Her commitment to clarity, accountability, and truth-telling is exactly what this moment demands. I’m proud to stand beside her—and even prouder to step aside when the story calls for her voice.

I’ve turned my focus to history, diving deep into the remarkable legacy of community involvement that shaped our hospital from 1900 to 2020. What I’ve found isn’t just inspiring—it’s instructive. This wasn’t passive support; it was active, persistent, and deeply personal. People showed up. They debated. They built. They held leaders accountable and made sure the hospital reflected the needs of the coast, not just the mandates of distant institutions. We can do this again, we can help both the board and Adventist by getting more involved with the board and them with us.

That level of participation is something we need to bring back—not just for nostalgia’s sake, but because our future depends on it. The hospital has always been a mirror of our civic health. If we want it to serve us well, we have to show up again to the district we pay taxes to and which owns it. Speak up. Ask questions. And remember that this place belongs to all of us.

At the recent board meeting, not a single person showed up—neither in person nor on Zoom—even though the agenda was about charting the entire future of our hospital. It’s hard to place all the blame on the board when the seats are empty. But the emptiness itself is a symptom. People don’t show up partly because the process isn’t intelligible. The language is opaque, the stakes are buried, and there’s little effort to go above and beyond in making it not just viewable but in the faces of the public- like the Skunk issue has been.

This isn’t just a communications failure—it’s a democratic one. When public institutions operate behind a veil of complexity, they don’t just lose participation. They lose trust. And when decisions are made without the public present, even if invited, they risk becoming disconnected from the very people they’re meant to serve.

We understand we’re asking a lot—especially when all the board members are working for free. But the deeper fault lies with the absentee owners of The Advocate News, who have drained it of resources, sold off its property, and left town. They continue to treat it as a cash cow, investing the bare minimum while the community clings to it—making it just profitable enough to bleed dry for another generation.

This isn’t just a business model. It’s a betrayal of public trust. A newspaper that once galvanized civic action now functions as a shell—printing press releases, avoiding scrutiny, and offering no meaningful coverage of the decisions that shape our lives. The loss isn’t just informational. It’s cultural. It’s democratic.eneration.

Reclaiming Our Voice, Reimagining Our Future

To me, outsiders robbed us of our newspaper. What was once a vital thread in the fabric of local life—a place where stories were told, issues debated, and neighbors informed—has been reduced to a bulletin board for press releases. The soul of The Advocate News has been hollowed out, leaving behind a shell that no longer reflects or serves the community it once helped shape.

Without real reporting, it’s hard to bring people together. It’s hard to share what’s truly going on, to hold power accountable, or to build the kind of shared understanding that makes civic life possible. Journalism isn’t just about information—it’s about connection. And when that connection is severed, the consequences ripple far beyond the newsroom.

So what do we do? We’re working on a plan—

We build a new kind of engagement—one rooted in transparency, participation, and shared purpose. We’re working on a plan to help everyone stay informed and get more involved in the decisions shaping our district board and the future of our hospital. Because right now, we worry the board has developed a habit of circling the wagons—hesitant to ask for public input, reluctant to seek community support, and cautious where boldness is needed.

We don’t see the sweeping vision that once came from the Union Lumber Company, which built with generosity and foresight. We don’t hear the moral clarity of Dr. Paul Bowman, who led with purpose for four decades. But that doesn’t mean it’s gone. It means it’s waiting—for us.

Today, I’m proud to introduce the new owners of the building where our hospital was born—a place steeped in history, resilience, and community spirit. Before Adventist Health arrived, this hospital was guided by a vision of local stewardship, built to serve and be shaped by the people of Fort Bragg. For decades, that model thrived, evolving through civic engagement, bold leadership, and a shared commitment to care.

But times changed. Healthcare systems grew more complex, and local resources stretched thin. In 2020, Adventist Health stepped in—and to their credit, they truly saved us. They inherited a facility mid-transition and faced the unprecedented challenge of a global pandemic before they even had a chance to settle in. Their response was swift, steady, and deeply appreciated.

As we reflect on the hospital’s legacy and look ahead to its future, we do so with gratitude for those who built it, those who sustained it, and those who now carry it forward.

This makes the job of the board more challenging than ever. How do they represent all those who pay for the hospital—we, the taxpayers?

It starts with remembering who the hospital belongs to. Not to Adventist Health. Not to consultants. But to the people of this district, who fund its infrastructure, rely on its services, and deserve a voice in its future.

Representation isn’t just about showing up to meetings—it’s about making sure those meetings are accessible, understandable, and responsive. It’s about translating complex decisions into plain language, inviting questions, and listening with humility. It’s about treating public input not as a formality, but as a foundation.

If the board wants to lead, it must first reflect and work harder to engage. Even if it means spending some of our tax money on that.. Reflect the diversity of its community. Reflect the concerns of its constituents. Reflect the legacy of civic engagement that built this hospital in the first place.

Yes, we elect them. Legally, that’s sufficient. But democracy isn’t just about legality—it’s about legitimacy. We also elect mayors and supervisors, and most of them understand that their job includes explaining what they’re doing to the people who pay their salaries. They engage. They communicate. They show up.

Our hospital board, by contrast, is made up of volunteers, supported by a single paid executive director, Kathy Wylie. They oversee a budget that rivals a small city’s—yet they operate with the staffing and transparency of a private landlord. One person prepares the budget. Decisions are made quietly. The board has withdrawn into a role that feels more like cashing rent checks than stewarding a public institution.

This isn’t a criticism of individuals—it’s a call to rethink the structure. If the board is going to shape the future of our hospital, it must also shape a new relationship with the public. One built on clarity, collaboration, and trust.

I would ask anyone curious about our hospital’s roots to read the old newspapers. The Fort Bragg Rotary Club, The Advocate News, the lumber mill, and local businesses all played active roles. I’ve read hundreds of those papers, and the hospital was often front-page news throughout the 20th century. The depth of community involvement was astonishing—sometimes even startling by today’s standards.

Back then, The Advocate reported every admission and discharge. “Uncle Bob checked into the hospital today with a bad cough—he seems to be doing better.” Or, “Mary was discharged after she fell and broke her wrist. Dr. Smith fixed her up!” The paper would even confirm if someone missed work due to injury, quoting the hospital directly: “Yes, they were truly injured and will likely miss work for three weeks.”

It was a different time. Privacy norms were looser, and the community’s connection to the hospital was deeply personal. The hospital wasn’t just a place of care—it was a shared civic endeavor, woven into the daily life of Fort Bragg.

All of this would be a criminal matter today under HIPAA. Anyone who released such personal health information would face prosecution. Society has changed—and not just in its laws. We’ve traded neighborhood familiarity for digital noise. We’re more acquainted with fake people, fake news, and robots on our phones than with the folks three houses down.

It’s not just that we lost the old intimacy. It’s that we stopped building new forms of connection to replace it. The hospital used to be a shared story. Now it’s a distant system. The newspaper used to be a mirror. Now it’s a bulletin board. And civic life used to be a conversation. Now it’s a calendar of meetings no one attends.

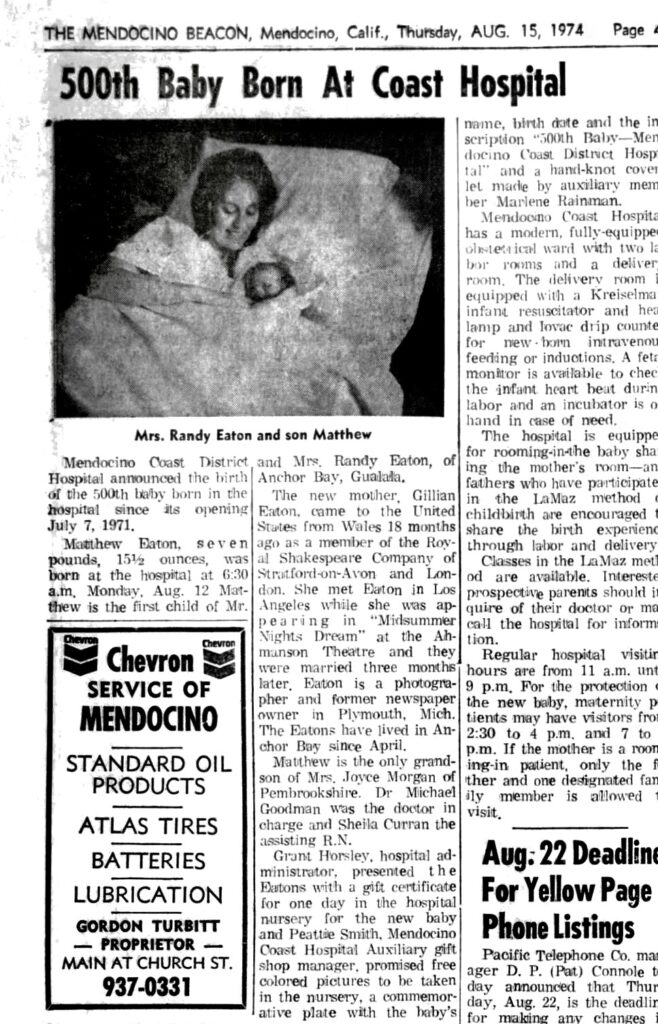

We don’t want to return to the days of invading people’s privacy. But I do miss the celebration of babies—the joy that once graced the front page with every first baby of the year, the 100th baby, the 500th. It was a civic milestone, a moment of shared pride. And although many in our community are still angry about the end of deliveries here, the reality is clear: Fort Bragg simply doesn’t have the birth volume to support a dedicated labor and delivery doctor right now.

Still, that doesn’t mean we should stop dreaming. Labor and delivery should remain in our quiver—a goal for the future, if and when the numbers make it viable again. Because times do change. And communities that plan for change are the ones that thrive.

Right now, our leadership seems stuck in a “now is forever” mindset—unwilling even to ask voters for a bond to fund the kind of hospital that could serve us for generations. That’s not vision. That’s stagnation. And it’s time we asked for more.

The town has aged. At one recent board meeting, we learned that the average hospital admission age is now 70—a stark indicator of how Fort Bragg’s population has changed over time. And as the town has grown older, so too has its institutional memory. Fortunately, I’ve kept a full record of The Advocate News going back more than a century. It’s a living archive of civic life, medical milestones, and community voices.

Back then, The Advocate and The Beacon were separate newspapers. The Beacon was better written—more polished and readable—but it didn’t dive into the granular details of Fort Bragg the way The Advocate did. To truly understand the hospital’s role in our town, you have to read both. Together, they offer a layered portrait of a community that once treated its hospital not just as a service, but as a shared endeavor.

I’ve unearthed some gems from our past—photos, cutlines, and stories that show just how deeply this community once cared. The hospital wasn’t just a building. It was a shared endeavor, a front-page priority, a source of pride. We can’t afford to drop the ball now.

Get involved. Attend board meetings. Ask questions. Being a local citizen means more than nodding along when someone in authority hands down a decision. This is still America. You are the authorities.

And take a moment to appreciate what the Dingmans are doing with the original hospital building. The craftsmanship, the vision—it’s a living tribute to the power of this community 110 years ago. They’ve lateraled that legacy to the district, which now carries the ball alongside Adventist. But we need to bring back the boldness, the imagination, the civic spirit that built it in the first place.

For Fort Bragg to thrive again, we need to pull our heads out of the sewer of national politics and start cheering on great local businesses. Love our hospital like the old timers did. Turn off the cable news. Tune in to your friends, your neighbors, your local economy—and your future.

Linda has submitted several Public Records Act requests to the district. When those documents come in, we’ll publish a second story—one that dives deeper into the decisions, communications, and financial details shaping our hospital’s future. Transparency isn’t just a principle; it’s a tool. And we intend to use it.