Skunk Train Wins federal recognition as a “Real Railroad” but what now?

In the great sci-fi book series “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the AI Supercomputer Deep Thought announces that it has done all the calculations and finally found the meaning of life.

The answer?

42.

This oddly prophetic moment—arriving amid the broader buzz about AI—feels like the long-awaited resolution to the question that’s kept Fort Bragg and the Skunk Train locked in a five-year standoff.

Is Mendocino Railway a whimsical tourist ride—or a gritty, nuts-and-bolts railroad?

The federal Surface Transportation Board spoke on Friday:

“It’s a real railroad.”

But then the computer shut down. The seemingly endless Deep Thought—and legal wrangling—is far from over.

The courts previously struck down the Skunk’s claim it is a public utility, a designation central to the ongoing debate, alongside its newly recognized common carrier status. The full meaning of Friday’s federal decision clarifying that the Skunk is in fact a real Class III railroad over the objections of the Coastal Commission will take time to unfold.

Let’s hope the Fort Bragg City Council doesn’t retreat into a closed session to sort out what it means and tell us all if it changes anything. This moment calls for public clarity, not backroom strategy.

Legally, they probably could—and may need to—seek advice behind closed doors. But they must also emerge from those sessions and hold a public meeting to explain what they believe this decision means. Ideally, the Skunk Train team would show up too, so the community can hear directly how this ruling might reshape our future.

To its credit, the City has been superb not just at holding open meetings, but at genuinely engaging the public. The hospital board—and others—should take note.

Hats off to Elise Cox and her Substack site Mendo Local for breaking this big story—complete with quotes from the Skunk Train’s booming-voiced, ever-friendly spokesman Chris Hart, who weighed in midday Saturday after the decision dropped late Friday..

Elise delivered a clear, even-handed breakdown of the decision in her Mendo Local article—cutting through the legal fog without editorial spin.

And we have provided a PDF of the decision as well

Just before Elise Cox’s report, the site trainorders.com broke the story—highlighting several intriguing details pulled directly from the federal decision.

“This ruling clarifying that Mendocino Railway is still a federally regulated common carrier is a significant win for the company. However, it does set up some interesting potential future legal fights, as the decision notes in one of the key passages, “ Trainorders.com reports, quoting the following from the decision:

“Regarding the Skunk’s request seeking clarification that it is entitled to any applicable protections of federal preemption, the Board agrees that (the Skunk) is entitled to whatever preemption would otherwise be applicable to a rail carrier however, the Board makes no finding with regard to the preemptive effects of (this finding) on any particular federal or state law or regulation.”

“Also, the footnote to the decision states “The Skunk has made clear that it is not seeking “any determinations with regard to the preemptive effects of any particular federal law or regulation,” and asserts that the “law on preemption is fairly well developed.””. “We now have a case where the railroad is still a common carrier at the Federal level but has not been locally recognized as such. Nor has the Skunk been recognized as a public utility at the state level, which puts the company in an interesting legal situation. Also hanging over all of this in the background is the adverse abandonment case against Mendocino Railway (not just the Skunk here) that the Great Redwood Trail Authority initiated a couple years ago, the last real activity on that case was a series of briefs filed by the parties in late 2024, it appears they are now waiting for some decision from the STB.” the Trainorders.com coverage states.

Once the question of public utility versus federal common carrier status is resolved, the city will still need to be sure that residents get what we need in the process, which will require a firm city hand in a process that has been slippery so far. The decision appears to affirm that the Skunk Train can continue upgrading its Fort Bragg railyards and railroad-dedicated property under regulations that apply to railroads—but not to local applicants who don’t own one.

Even in the most favorable outcome for the Skunk, this does not grant special rights to develop the broader millsite for housing or other non-railroad uses. Their current plans for a major train station and railroad center at the end of Redwood Avenue do include a hotel and conference center encircled by tracks, so that portion may qualify.

The Skunk hasn’t sought special treatment for its proposed housing north of the planned railroad center. But if the track is extended to Glass Beach Station as envisioned, how might its Common Carrier status affect development adjacent to those tracks? This is a question we need the city to go to bat for us on.

With so much still in flux and open to interpretation, we’ve opted—like our two respected rivals above—to simply report the decision. Let’s all follow along and see what actually unfolds next.

Ironically, the two main combatants in the legal battle—the California Coastal Commission and the Skunk Train—joined about 80 members of the public and city officials for a site tour. Chris Hart narrated the walk-through for the Commission, explaining that all proposed developments were still in the planning stages.

Hart noted that the historic north-south layout of the current Skunk Station has long blocked public access to the headlands. In contrast, the evolving plans for a new station at the end of Redwood Avenue would feature an east-west orientation, allowing pedestrians to walk from downtown, past the trains, and into a newly designed 3.65-acre park area inside the railroad center.

From there, visitors could access the Coastal Trail to the west (not part of Skunk property) or explore a proposed 40-acre nature center near the old mill pond. That area remains polluted from mill-era remnants, so any public access beyond viewing may be a long way off.

What does the Surface Transportation Board’s decision actually mean? Historically, the City and the California Coastal Commission might have hoped for a successful appeal—and they still may file one within the 90-day window. But the regulatory winds have shifted.

The Surface Transportation Board (STB has two people appointed by President Trump and one by President Biden. The STB has increasingly backed decisions that expand the definition of what a railroad is—and what it can do. Recent rulings reflect a new era of railroading, with the STB pushing the envelope on federal carrier rights. While federal appeals courts have struck down some of these decisions, the current U.S. Supreme Court has reversed those rulings, reinforcing the STB’s authority.

One key clarification from the Board: a Class III carrier doesn’t lose its railroad status simply by ceasing to carry freight. To relinquish that designation, the railroad would have to formally walk away from its federal status—and the STB would have to explicitly revoke it.

There’s still widespread confusion about what it means to be a federally recognized carrier around the nation, the STB has stated, which is one reason the apparently unanimous decision was made. This decision doesn’t resolve all the questions—but it does set the stage for a very different conversation about land use, local control, and the future of Fort Bragg’s rail corridor.

As an example of the current regulatory climate—favoring fossil fuel infrastructure and rolling back environmental oversight—the U.S. Supreme Court recently upheld a decision allowing an oil train project in Utah. Local governments and environmental groups had successfully challenged the project in federal court, with the D.C. Circuit vacating the Surface Transportation Board’s approval. But the Supreme Court reversed that ruling, siding with the STB and reinforcing its authority.

This anti-environmental national legal climate matters in Fort Bragg. It signals that even if local agencies or environmental advocates challenge the Skunk Train’s federal status or land use plans, they may face an uphill battle in court. The STB’s decisions are being backed at the highest level, and the definition of what qualifies as “railroad use” is expanding.

In this new era of rail-friendly rulings, Fort Bragg’s future may hinge less on local zoning and more on how federal regulators interpret the reach of a Class III carrier. That’s why public engagement—and clarity from the City Council—is more critical than ever.

The Surface Transportation Board celebrated the decision in language that echoes the partisan tone of Trump-era agencies—a style that, not long ago, would have been startling coming from a federal body. But Trump has ushered in a new regulatory reality, where the force of his ideas often overrides long-standing protocols. And for now, it’s working.

“The Surface Transportation Board (on May 29) announced that the Supreme Court of the United States has issued a favorable and unanimous decision concerning the Board’s 2021 decision approving the construction and operation of a new rail line in Utah’s Uinta Basin for the primary purpose of transporting oil. Today’s decision reins in the scope of environmental reviews that are unnecessarily hindering and potentially preventing infrastructure construction throughout the country.” (this is about the oil train and has nothing to do with the Skunk issue)

Rolling back environmental review processes has been a central goal of the Trump Administration—and one it’s accomplishing with unmistakable gusto.

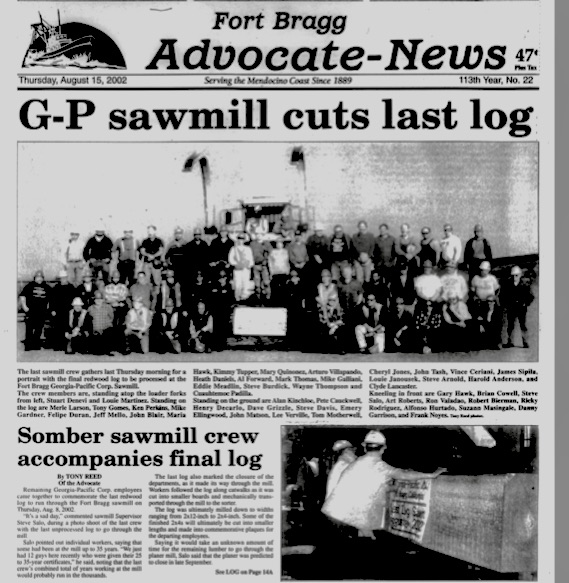

This national story really doesn’t tell what is happening here. Fort Bragg is still recovering from the biggest trauma of its existence, the closure of its anchoring lumber mill by Georgia Pacific in 2002. Generations of locals had good jobs there and in the Louisiana Pacific mill down the road. Suddenly, they were all gone. Mendocino County loggers whacked trees at a staggering and unsustainable rate for the century prior to 2002. With the big redwoods mostly gone by the 1970s, there was no longer a reason to have a mill here. Shortly thereafter, the California Western Railroad went bankrupt and the Hart family and Sierra Railroad were treated as saviors. The town wrangled what to do with the abandoned and polluted millsite for almost 20 years before the Skunk got the property through purchases and a friendly eminent domain proceeding with Georgia Pacific, with GP/Koch Brothers long eager to get out of town.

The low price the railroad paid and some ham-handed negotiating by both sides in the public and private spheres led to the ownership being treated as a local pariah more than a savior. They maintained that the railroad had always gone with the lumber mill, which was true. But neither the city nor the Skunk expressed a public interest in the property for more than a decade before the ugly public battle over the transaction. And they both changed their positions over time on a wide range of issues, such as the Dry Sheds, in my opinion.

The Hart family controls a network of Northern California railroads and affiliated companies—some of which are bona fide freight carriers, though not all share identical ownership structures. The Skunk operation in Willits also falls under Mendocino Railway and its connected entities. Willits Skunk/Mendocino Railyway has to be a real railroad by any standard It has certainly played a role in building real railroads, but its efforts to reconnect Northern California’s economic infrastructure have been repeatedly blocked—most notably by the Great Redwood Trail initiative and other regulatory hurdles.

Robert Pinoli, president of Mendocino Railway—better known locally as the Skunk Train—and affectionately dubbed “Chief Skunk,” also took part in the tour.

For this article, we’re sticking with “The Skunk”—a name that keeps the spotlight on the entity that owns the 400 acres forming Fort Bragg’s western frontier, at least up to the Coastal Trail.

Locally, the environmental implications of the decision relate primarily to future permitting. There’s no indication it will affect the most pressing issue: cleanup of the old Millsite.

The main remediation area is a 40-acre stretch just north of the city’s sewer treatment facility, right on the oceanfront and squarely in the heart of the former millsite. The Skunk—and any past or future owners of the property—remain liable for addressing the contamination there. This mess isn’t going anywhere for a long time, if ever. It may be better to leave and contain? Science will change with time. Also, the long desired burying or daylighting of creeks is still possible The entire city buried those same creeks beneath it when Fort Bragg was built.

The Skunk has been called as an “excursion” or tourist ride because it goes only 3.5 miles east of Fort Bragg. A leaky old tunne built in 1893 collapsed—first in 2013, then fully in 2015—about 3.5 miles east of Fort Bragg, severing access to the remaining 36 miles of track to Willits. But the city and Skunk worked together until the battle over the land deal and local anger over work being done without permits. At first, some of the work looked dicey, but as time went on the railroad did first rate repairs to buildings that appeared dangerous to this reporter. The Skunk did an eminent domain action to take land from a property owner near Willits. This stirred considerable outrage.

In response to the tunnel collapse, the Skunk pivoted. It launched its now-popular (and increasingly pricey) railbikes and transformed the tunnel’s edge into a weekend venue for music, weddings, and events—recasting the line as a destination experience rather than a through-route. Then the city and Skunk ended up in court with arguments over storm water pollution, eminent domain powers and

Tunnel Repair Status A fix of Tunnel #1, the collapsed section that severed the Skunk Train’s connection to Willits, is still in the works. Mendocino Railway recently secured a $31.4 million federal Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) loan—shared with Sierra Northern Railway—to restore infrastructure, including Tunnel #1. Engineering firm LACO Associates has been contracted to oversee geotechnical evaluations, structural reinforcements, and construction-phase serviceslacoassociates.com. The Coastal Commission delayed the tunnel shutdown with an environmental challenge in 2024 but the railroad has been telling railroad magazines that is over after a review by the Federal Railroad Administration. If the decision has any immediate impact it would likely be on the tunnel project.

$31.4 million federal Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing

Skunk Train Tunnel Repair LACO

A series of legal battles over the Skunk’s plans eroded public support in Fort Bragg, reaching a peak around 2022. But more recent public forums and election results suggest a shift: many residents are weary of the prolonged conflict and eager to see real progress on the millsite.

The decision wasn’t a full victory for the Skunk, and the City must stay firmly in control of the process. That means requiring performance bonds, locking in a detailed site plan, and negotiating binding developer agreements that define exactly what goes where. Only then can the Skunk move forward with long-term development—without depending on who happens to sit on the Council.

As longtime observers of this process, we hope the City continues its strong leadership in fostering public involvement and open dialogue. Another well-attended Town Hall may be in order. It’s unfortunate that other local entities don’t work as hard to engage the public—though we recognize they lack the budget the City has skillfully built through nimble grant acquisitions.

In its most recent election, the Fort Bragg Unified School Board broke from tradition—choosing not to fully explain its proposed tax bond or engage the public as it had in the past. The result? A razor-thin win for school funding. And let’s be clear: winning by a hair isn’t winning when it comes to our kids.

We must engage. Democratic institutions—especially those rooted in public health, education, and safety—depend on active participation. If we tune out, we risk compromising the very systems that hold our community together. This is still America. Let’s act like it.

In our view, the Mendocino Coast Hospital District has also fallen short in engaging the public around dramatic plans now underway for the hospital’s future. To be clear, both the school board and hospital board are made up of some of the finest people in town—dedicated volunteers who give generously of their time. But even with the best intentions, public engagement can’t be optional. And while we understand these are rushed and complex times, that’s all the more reason to bring the community in, not shut it out.

But more public engagement is urgently needed. We’ve also documented how our state and local court systems have become increasingly inaccessible—making it difficult for the public to meaningfully access records or track decisions that affect their lives.

These entities need to consult with the City, engage the public, and hold open meetings about the future. Set up discussion stations. Knock on doors if needed. Beg people to get involved. Because without public participation, even the best plans risk falling flat.

Not a single member of the public—or even a Zoom attendee—showed up to a recent hospital board planning session. And that’s a future being shaped for the entire coast, from Westport to the South Coast.

The deeper problem lies with the hedge fund operators who now control nearly every newspaper in California. They’ve refused to sell, drained every last penny, and left our communities with nothing in return. This extractive, Wall Street-style ethic—once unthinkable in American journalism—now touches every town in the country.

The colonizers have come for us again. This time, they’re not laying rail or cutting timber—they’re gutting our civic infrastructure and selling off the soul of local media..

That’s why we’re lucky the Harts own the railroad. For all the ups, downs, and a few wacky chapters before Chris Hart stepped in as spokesman and spinmaster, this remains a family-owned company—not some dreadful, vampiric hedge fund bleeding communities dry.re hedge fund.

They want to rebuild a key piece of our infrastructure—and we can work with that. But make no mistake: they’ll push the envelope and try to get everything they can. The City must be ready to meet them head-on, negotiate smart, and hold the line where it matters.

To us, this means negotiating updated developer agreements that allow the Skunk to build rail across the entire site—while holding firm on cleanup obligations and refusing blanket approvals for any development, especially railroad stations or a hotel-conference center.

There’s room for bold collaboration here. The Skunk, the City, and the tribe south of the millsite could explore an elevated vacuum rail system running through Noyo Harbor and even across to the south side. The technology exists. We’d also like to see industrial development return to the southern end of the site—reviving jobs and purpose.

And why not dream big? A monorail across town. A federal common carrier that moves both freight and people. Land trades with tribal partners. Forest mitigation is done collectively. The pieces are here. It’s time to connect them.

We’d love to see the Great Redwood Trail reimagined into something far more visionary than its current form—which, as it stands, feels like a boondoggle for out-of-town consultants, a party for places like Ukiah, and a nightmare for rural landowners along the route. What’s being pitched now is a hiking-only trail that cuts through properties that once agreed to host a railroad, not campers sleeping in barns.

It could be so much more. Imagine an electric elevated train route, with opportunities for farmworker housing and regenerative agriculture along the corridor. But the process has been, frankly, corrupt and closed. My nephew Joel became the first person to through-hike the trail—321 miles – starting with the train in Marin and finishing on foot in Manila, Humboldt County. We tried to offer ideas, tried to engage. But the trail’s leadership has been as closed to collaboration as the Eel River Canyon is to any future rail.

A railroad might seem outdated—but not as outdated as trying to copy the Appalachian Trail, which was innovative in 1921 and has since evolved. We don’t know if the Skunk is even interested in electric trains or monorails, but these are the kinds of ideas we should be exploring.

Let’s work together to get the tunnel fixed and reopen this economic artery. Times are changing fast. Let’s stop spinning in circles, sort out this confusing mess, and move forward with vision.

Times are changing fast. The world ahead won’t look like the one we know now—and that’s exactly why we need to act with clarity and courage. We need a railroad here. We need that tunnel fixed. Not just for nostalgia, or tourism, or freight—but for resilience, for connection, for a future that honors our past while daring to imagine something better.

Let’s stop letting hedge funds and consultants define our destiny. Let’s build it ourselves—with rail, with vision, with community at the center. The millsite, the canyon, the harbor, the town—they’re all part of the same story. And it’s ours to write.

So let’s get to it.

Frank Hartzell, working with the Mendocino Voice, broke several stories that neither the city or the Skunk wanted to talk about at the time, in my opinion. (To stave off the usual attacks to make points). The following suit remains active and we plan an update on that.

Skunk Train sues city of Fort Bragg over stormwater runoff into its property

This property transfer remains a bit of a mystery to me.

Skunk Train sells property in internal transfer

Frank with KZYX, reported on the big meeting that herald a new era in Skunk-City relations.Newscast: Visioning Workshop Is First Step in Developing Fort Bragg Mill Site

We’d all love the Skunk to stand up and stop playing the angles and for every advantage and take leadership. They could stop trying to win battles and win the war for our future. We’d love to see a rail network connecting Noyo Harbor, the Boatyard through the Millsite and out to the schools and hospital. But they would have to discard some of the game playing that has gone on, in my opinion.

Friend on Facebook Chris Cisper said it very well after this story came out. LOTS of people feel like this in town.

‘If they make a train that can be used to move goods and people (locals doing business) at a reasonable rate, well I might be okay with it but right now I feel like Charle Brown.”