The 1970s brought a peculiar terror: that California, land of sunshine and seismic fault lines, would one day slide into the Pacific Ocean.

Don’t laugh too hard—our collective imagination still runs wild, and we believe far sillier myths today.

The hysteria may have faded, but the reality is stark: beyond Pacific Star Winery, the Mendocino Coast is crumbling into the sea. Caltrans concedes Highway 1 would have disappeared years ago without emergency fixes at Blues Beach and Juan Creek.

What began as a decade-long battle with Mother Nature turned into erasing a beach and plumbing a mountain this summer at Blues Beach. The crisis, decades in the making, deepened after another punishing winter and the earthquake that rattled the coast in late 2024.

Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency at Chadbourne Gulch–Blues Beach, sweeping aside most environmental laws and sacrificing nearly half a mile of the beach’s north end with a total transformation of a beach into a rockpile, something rarely, if ever seen in California history. The crisis is no less dire at Juan Creek, north of Westport, where the town would have been cut off by mudslides in both directions without Caltrans—the state’s road‑building lifeline.

Geologic challenges lurk everywhere along the Coast, and some very scary threats to State Route 1. Some are simply on the coming projects list and several of the worst are not on the list

North to South

- Fort Bragg- culverts failed under Hwy 1 by Paul Bunyan Thrift Shop

- A major slide is pushing Hwy 1 to the west above the SOUTH end of Blues Beach. Nothing is currently being done about this looming problem, but its on the list

- A state of emergency was declared last summer in the decades-long fight to save Hwy 1 above the north end of Blues Beach

- Just Westport, a mostly invisible problem is happening to Hwy 1 at the Westport Campground. A culvert has failed there and is a very difficult corner to work on. This is in the plans but has not begun. A vexing problem but nothing on the scale of the others

- Juan Creek- the highway came the closest failing here last winter- inches left were filled by a concrete patch- then a summer of taking more land to the east and a massive project to slice the entire hill back so the highway can be moved east

- A second slide above the South end of Blues Beach. There are two major slides happening above the South End of Blue Beach, shown in the photos that include my big foot at the end. Below both, the ocean has intruded and caused major slumping of the hillsides right up to the road. Neither are on the list, but are much worse long term than the two smaller ones listed above.

The question now is how long humans can keep defying Mother Nature—and whether our solutions will hold. Throwing steel, stone, and ingenuity at Mother Nature before she takes it all back?

“The worst case on the wall is down there, Wright says, pointing south. It has moved seven feet out and four feet down from where it was built,”

GEOFFREY WRIGHT OF CALTRANS ABOVE BLUES BEACH

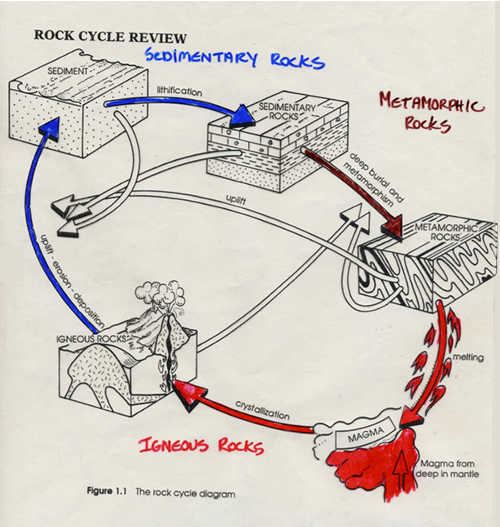

Let’s examine how the crumbly Franciscan Complex threatens the future of Highway 1 north of Pacific Star Winery.

We found a dozen highway spots so worrisome that anywhere else each would merit its own headline. State Route 1 is cracked, shifted, and flanked by canyons dropping 50 to 100 feet toward the beach. Touring the area with Caltrans’ Geoffrey Wright, we saw firsthand the risks the agency has cataloged and ranked. Two of the worst sites already require traffic lights. A third, just east of Westport Campground on the downhill stretch, could trigger even greater delays next summer if no solution is found short of closing the highway. For now, the danger is invisible to passersby—hard to see, even when walking the road.

Even setting aside Juan Creek and Blues Beach for a moment, Caltrans’ response to these looming disasters is nothing short of astonishing.

Blues Beach’s fix comes down to two things—boulders and plumbing. Yet the scale of both is unprecedented.

At Juan Creek, the fix is what engineers call ‘slicing the pie.’ Here, the road came perilously close to failing, as the photos show. Last winter, the width of the area between the ocean and the highway shrunk from 18 feet to 3 feet!! And as you can see in the photos, it went even further than that in one place. Caltrans’ answer is to shift Highway 1 eastward, carving back the hillside as if it were a gigantic ham, sliced by a butcher into sandwich cuts. Hundreds of truckload of fill have been trucked down to fill in old quarries along the 10 mile River, at the Parker Ranch, where along with the Smith Ranch, one of the most massive river and watershed restorations in modern California history is underway.

The problem is the work cuts deep into private property, leaving at least one home perched above a canyon that has been created where their backyard used to be. People were paid by the state, but they lost their private dream home to now being very close to the precipice.

Moving Highway 1 east won’t work above Blues Beach—the hill to the east is little more than super massive sliding pile of mud, pushing the road toward the precipice. The solution: a massive plumbing system drilled into the hillside. Engineers believe it can hold, and the plans are impressive. Yet everyone we spoke with, from construction crews to locals, asks the same haunting question: how long can you fight Mother Nature and Father Time?

Blues Beach, as we knew it, is gone for good. It will remain closed for another year before reopening under new ownership and strict new rules. The California Coastal Commission ensured this by transferring the property to Kai Pomo, a tribal non‑profit collective. The handoff begins just north of Pacific Star Winery and stretches across a mile of bluffs and tide‑washed rocks thick with mussels and ocean life. The Commission also ordered the three Mendocino Coast Tribal entities to end the overnight revelry that once defined Blues Beach. From now on, the beach must close at dusk and reopen at dawn—or risk being reclaimed by the state.

Caltrans originally presented plans for a 46-foot-high seawall (an incredible height halfway up the existing hill) This was based on the maximum projection of an angry ocean with climate change forecasts figured in. The Coastal Commission reduced that to 38 feet because the foot of the 46-foot-tall seawall would have been so wide that safe access to any part of the north end of the beach at anything but low tide would have been eliminated. So the Coastal Commission saved a sliver of beach below and got ten feet shorter rock mountain. The entire wall was secured by burying boulders beneath the section of North Blues Beach that has been obliterated by the project. There is a sci fi worthy reality warping at the construction site above Blues Beach. People have been driving through traffic signals there for decades and think nothing has really changed. But actually the entire road and everything else has already gone out to sea,

“The worst case on the wall is down there, Wright says, pointing south. It has moved seven feet out and four feet down from where it was built,”

The wall is a massive concrete and steel girder that was installed just west of the highway a decade ago.

”If we had not put the retaining wall in, the highway would have been gone by now”

The wall is deep and long enough to hold the entire highway and its foundation together even it is pushed west by the sheer creeping mass of a continuous, slow-moving landslide.

Everything had to be done with no concrete or any modern construction grouts, glues or other manmade matmerials. Its all boulders all the time.

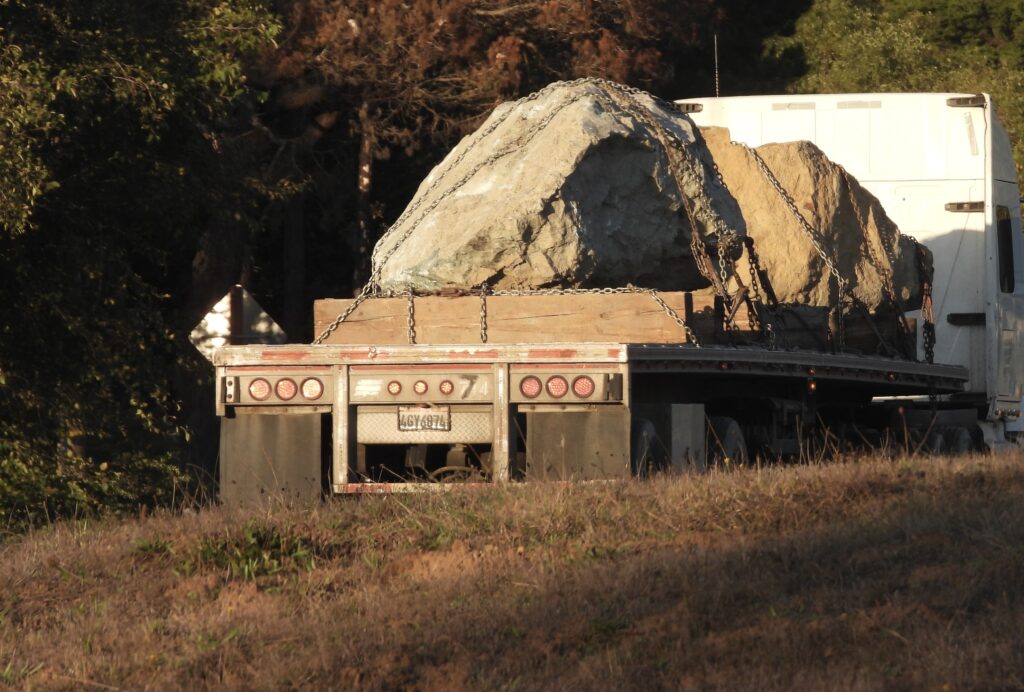

The boulders cost Caltrans $165 to $195 per ton delivered, making the use of boulders much cheaper than any solutions. And the use of these “revestments” has worked all over the state and is becoming the new way to stop erosion by oceans, big lakes and rivers. With no artificial substances allowed, boulders have to be engineered as if they were some ancient temple built of rock only, before the invention of mortars and Roman concrete. Use of oils in the machines working on the beach (and what used to be the beach) is also tightly controlled in the project. Myers is placing the boulders and fill at the rate of 800-1500 tons per day since the project started, Caltrans officials heard in October when all the top brass from HQ in Sacramento northward visited both sites, and all the other major projects across the state.

Among all the shocking aspects of all this is the fact that the state can give land to the indigenous people then take it back. This brings to mind so many stories of broken treaties. Government givers?

It can happen because this is not a reservation, but a new form of collective tribal stewardship, which apparently is revokable. The state is keeping the north end of what used to be Blues Beach for continued highway repair. But possibly worse is the south end of the beach, promised to the tribes and title all ready to transfer. But another potential failure looms there that might require Caltrans to intervene on that end as well,

Will driving ever return to Blues Beach? Someday that decision will be made, but it’s highly unlikely—and if it does, it won’t resemble the free‑for‑all of the past. For now, Blues Beach is closed except for a pedestrian walkway to the South end. The entire half‑mile north end has been buried beneath a massive construction pad. We’ve never seen a beach of this scale permanently entombed under rock, yet that is exactly what’s happening. Since July, more than 12,000 giant boulders have been hauled in from quarries across the region, rolling down local roads seven days a week. We’ve counted anywhere from 12 to 30 trucks in a single hour. And the rock wall is only half the project. Inside the slumping 250‑foot hill that presses Highway 1 toward the Pacific, engineers are installing a vast plumbing system. Failure was described as imminent before this emergency work began in July.

The tribes will not gain the north end of Blues Beach. They will, however, have access through the site, and at the far north end they are being granted another spectacular bluff property from the Mendocino Land Trust.ust.

In Westport, the Village Society has spent the past 20 years creating a spectacular park, opening beach access, and managing property with the promise of future expansion. But just north of town lies another small spot with outsized consequences: pipes have failed in a tiny creeklet beneath Highway 1, east of the Westport Campground. On the other side of the campground, a massive restoration project has begun. The remnants of Old Highway 1 have been removed, and the first steps of a walking and biking trail are underway. This summer, sterile grass seed was sprayed—a literally groundbreaking technology that binds seed to inert material so it won’t wash away. The seeds are sterile to prevent the non‑native cover crop from becoming invasive.

All around, invasive pampas grass continues its double role: polluting the ecosystem by crowding out endemic species, while still performing its original job of holding the hillside. To counter this, Caltrans is funding a native plant operation—species that can stabilize slopes, feed birds, and coexist with the underground web of mushrooms and microbes, building a sustainable ecosystem. The restoration is required mitigation for the destruction of Blues Beach’s north end.

Continuing north, Juan Creek hosts another colossal project. A 150‑foot crane, fully extended, was used to drape huge steel nets across an entire hillside. The nets were installed by specialized crews—half construction experts, half acrobats, likened to the Flying Wallendas as they worked suspended on cables, performing a repair-circus as watchable as one under the Big Top.. Highway 1 is in peril here too. But unlike Blues Beach, where there is no room to shift east, engineers have been slicing the hill back regularly—like a butcher carving slices from a mountain‑sized ham. That strategy has meant taking more property to the east by eminent domain. This time, Caltrans increased compensation after property owners argued they had been underpaid, even as they accepted the highway creeping ever closer to their large and valuable homes.

Below, the boulders and loaded, trucked 1/3 mile to the end of Blues Beach, unloaded, the rocks piled high, and the truck returns for more, stopping only for a matter of a few minutes

At MendocinoCoast.news, we’ll keep bringing you these stories—along with the photos that reveal the reality on the ground.

The coast is crumbling everywhere. It sits atop the Franciscan Complex—a geologic jumble born, melted, and shattered over millions of years. It was collapsing long before humans arrived 15,000 years ago, and long before the highway‑builders showed up just 175 years back.

Fort Bragg was built atop all this—including creeks. Building a city partly on water is hardly a recipe for easy public works. For 20 years, George Rinehardt has championed ‘daylighting’ the creeks that flow onto the millsite. Once dismissed as environmentally extreme, the idea now proves to be economically sound as well. Underground, creeks tend to misbehave. Freed, they restore nature faster.

Every road fixer and engineer we spoke with gave the same warning: this problem will only grow worse with time. Should we pour more than $200 million into just two of these projects in 2025–2026? What choice do we have? The coast is crumbling, the clock is ticking.

Stay tuned. More info after the photos.

The Crisis at Blues Beach (from Frank’s story in Real Estate Magazine)

- The Westport landslide complex (on and above what locals know as Blues Beach) sits along a steep stretch of California’s Mendocino coast, where State Route 1 hugs the cliffs about 250 feet above the Pacific.

- Years of coastal erosion, worsened by severe winter storms, have triggered a series of nested, overlapping landslides. These are now threatening the structural integrity of the highway.

- Governor Gavin Newsom declared it a critical emergency due to the “imminent failure” of the road—a rare and serious designation that unlocks rapid-response funding and resources.

The Drastic Response

- Caltrans jumped to launch a $110 million emergency repair project to stabilize the area.

- Crews are installing soldier pile ground anchor walls (steel piers that are hydraulically driven into the ground until they reach competent soils or bedrock), coastal rock revetments, (a facing of impact-resistant material, such as stone, concrete, sandbags, or wooden piles, applied to a bank or wall in order to absorb and diffuse the energy of incoming water and protect it from erosion—in this case it’s massive boulders), and drainage systems (which eliminate the danger of water turning the substrate to mud) to slow the slide and protect the road.

- Access to Blues Beach is now restricted, with 24/7 one-way traffic control in place and delays inevitable while the immense project moves forward.

Why It Matters

State Route 1 isn’t just scenic—it’s vital. It connects isolated communities, supports tourism, and serves as a lifeline during emergencies. Losing it would be more than inconvenient—it would be economically and socially disruptive.

First, Caltrans and its contractor, Myers & Sons Construction, buried the entrance to Blues Beach beneath a fortress of interlocked boulders—creating a launching pad for what came next. From that foundation, they effectively erased the north end of Blues Beach, erecting a double-tiered seawall and a massive roadway that now towers two to eight feet above what was once a third of a mile of untouched shoreline. Not since the logging era over a century ago has anything of this scale been built on a Mendocino County beach. And Caltrans did it in just a matter of weeks.

Why?

A 250-foot oceanfront mountain is tilting westward, its slow-motion descent threatening to shove the slender ribbon of highway straight into oblivion. Far below this geological unrest, the deep blue sea continues its relentless feast—devouring the land that once held the road firm.

With a $110 million budget and a target completion date of September 2026, Caltrans enlisted Myers and Sons Construction—a firm that has built a reputation for tackling challenges deemed impossible by others. Caltrans and Myers are tackling the most significant Mendocino Coast road emergency in a century with an ambitious, two-phase strategy.

The Strategy

1. Transporting over 13,000 massive boulders, totaling at least 180 million pounds. Caltrans is purchasing the largest rocks available anywhere in the state, while Myers and its subcontractors have been scrambling to secure enough trucks and drivers to maintain a steady flow of boulders from multiple directions. It’s no exaggeration to say that boulder-hauling trucks now rival the number of logging trucks on Mendocino Coast roads.

Individual boulders range in weight from one ton to over fourteen tons, with most averaging between six and eight tons. Some truckers have reported hauling boulders as heavy as twenty-two tons.

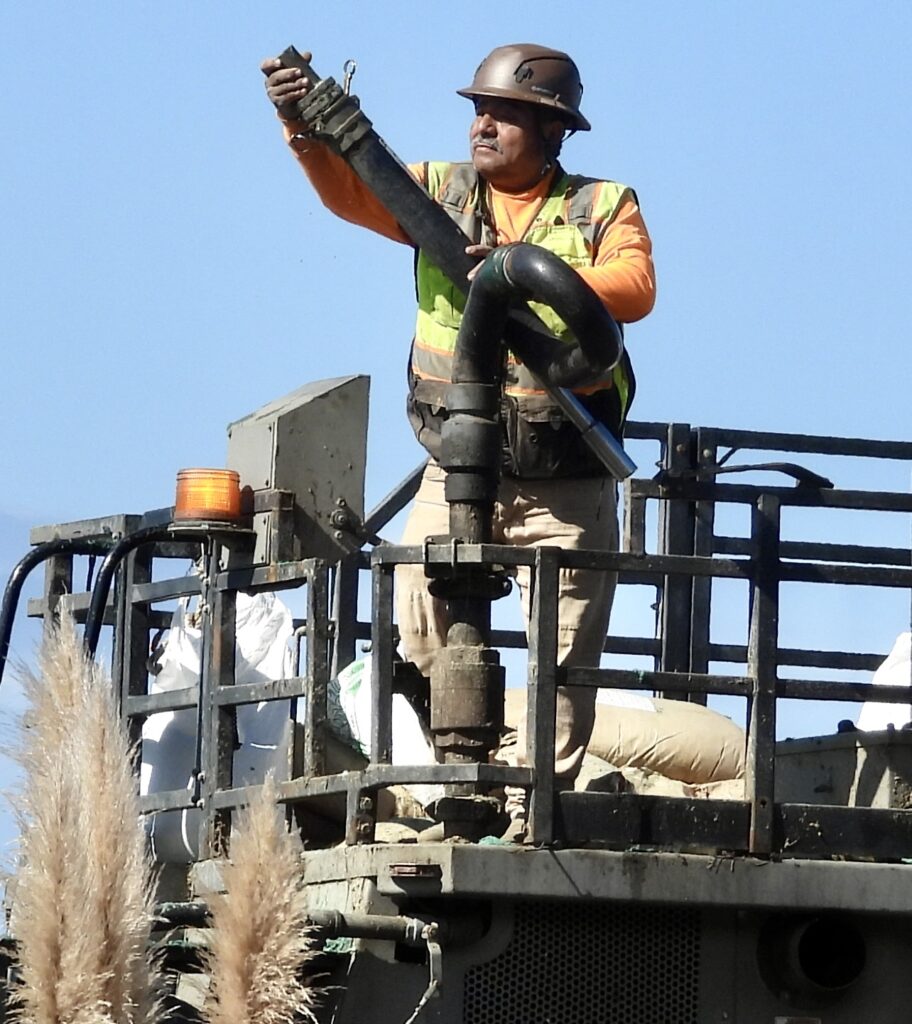

“For the Westport Landslide, rock is being sourced from more than ten separate quarries, with 1,200 to 1,500 tons being delivered to the site daily. That’s roughly 170 individual boulders each day,” said Manny Machado, spokesman for Caltrans District 1.

2. Even more critical to saving the highway is a bold, innovative strategy to remove water from a massive hill—bordering on a small mountain—that has remained geologically saturated for millions of years. Most of the water management, the core challenge of the entire project, is now under control, except for a slow-moving landslide spanning 1,400 feet. Installation of the newly engineered dewater drainage system begins in October and is considered most crucial. A wet winter could accelerate the slide’s movement, but it will also serve as a real-world test of the contractor’s dewatering solution.

According to project documents, a December earthquake that struck the Mendocino Coast last year worsened conditions. Also, to mitigate future risks, a state-of-the-art monitoring system will be installed and remain in place long after construction ends. This will enable real- time problems that could arise with either the dewatering system to the east or the gigantic rock structures to the west to be reacted to more quickly.

“The Westport Landslide is massive, but it’s now possible to track movement at this scale by installing subsurface drainage systems,” said Machado.

Part one is boulders, part two is bringing in the plumbers, not the first construction trade one might think of for taming the wilderness and being the star of a massive construction site where four huge excavators worked simultaneously. We watched these plumbing crews pushing pipes into the base of the giant pile of boulders. They really get to be the stars up top this winter.

“We’ll put that drill rig in the closed northbound lane, and we’ll try to put horizontal drains all the way along here at roadway level to try to get water out of the hillside and hopefully relieve some of that water weight that’s in the dirt and hopefully slow the rate of failure,” Wright said.

Due to the urgent threat of losing the highway entirely, the California Coastal Commission—along with all other environmental and land use regulators—has temporarily suspended oversight of the project. Regulatory review will resume only once it’s clear that Highway 1 can be preserved.

“Ensuring a reliable and resilient Highway 1 at the site known as the ‘Westport Landslide’ is a top priority for Caltrans District 1,” continued Machado. “The location presents uniquely complex challenges, compounded by the absence of any viable alternate route.”

In just four months, the high-speed Mendocino slide project has erected an enormous seawall that runs along the unstable mountainside and climbs high up the towering coastal cliffs.

Myers, which only began work on June 27, has already scored an early victory against Mother Nature in Westport. Initially, crews had to wait for low tide to haul boulders down the beach. Now, with the lower tier completed, the road sits roughly eight feet above the original beach level—high enough that even summer tides are held back, despite the fortifications still underway. While a winter storm could pose a serious setback, each day of rapid progress makes that scenario increasingly unlikely.

There are many ways to tell this multifaceted story but one really has to go there and see it with one’s own eyes. A group of people has been doing just that this summer. Reporter Frank Hartzell has made 100 trips to the site this spring and summer. There are at a roadside pulloff that appears as if it was made to observe this awe-inspiring scene of mankind confronting a relentless Mother Nature in her most truly divine of settings, some people have been watching a true reality show that dwarfs those contrived for television.mmm

Myers and Sons Construction’s massive excavators, dump trucks and tractor trailers all managed near perpetual motion. It is a baton race that seems to have defied physics and achieved perpetual motion.

One grasps for the correct metaphor to match what we have been seeing.

The pad works like a giant clock with hands that never stop turning. One big semi comes in and never stops rolling. It goes to the furthest of two unloading points, turning and backing up to a crane on the edge of the pad, which takes the boulders and moves them into big dump trucks, which then drive ¼ mile north on a massive temporary road built on the beach. While that truck is unloading, another pulls into the closest spot. That trucker doesn’t have to back up. Another crane unloads his flatbed of the giant boulders, which range from 3 to 8 on a 40-foot flatbed. That crane swings those over to a dump truck in a different location. On the far end of the beach, my Nikon P1000 reveals clouds of dust, people in orange outfits doing a beach version of air traffic controllers, one truck dumping, another leaving with two big cranes placing the boulders in the towering seawall according to a predetermined map and grid.

The choreography is accomplished using lots of planning but ultimately relies on highly paid operators of the 6 cranes on site, these grown-up 8th-grade boys who have won the competition. Yes! They get to play with THE coolest toys. Engineering, logistics and planning all work together to give that operator the right choice of stones but the operator has to eyeball it and actually fit these puzzle pieces together.mmmmmmmm

When Frank was in college at Humboldt State his geology professor, the late John Longshore, was hired as a consultant on a proposed road project and he told them it was impossible. They didn’t ever hire him again but were, as he predicted still entangled in a multimillion-dollar effort to save that road that had quadrupled the intiial budget, more than a decade later. He said the builders had won what they were trying to win— by spending lots of money, not finding a realistic, long term solution.

He said hundreds of millions would be wasted because of the “we sent a man to the moon,” mentality. He predicted during our class that eventually, a few weak points on State Routes 1, 101 and 299 would see the total defeat of state engineers.

He said millions would be wasted because Americans simply cannot accept the notion that some things are impossible,even when they are, especially when they seem much more mundane than moon landings.

20 years after graduation I called to congratulate him when his prediction came true on Highway 101 at Confusion Hill.

He said there would be more road failures as time went on and billions, not millions, would likely be wasted trying to win unwinnable engineering challenges.

Is that true here? We likely won’t find out till the money gets spent.

Photos above taken at the peak of king tides on Dec. 4.

The project brought some companies famous in the trade for their hutzpah to the Coast. Access Limited is a subcontractor on Juan Creek, construction worker- acrobats who can do work on a cliff face that most of us would have a hard time doing on the flat. Granite Construction, one of the biggest contractors in the state is the Prime Contractor at the Juan Creek Project and a local firm, Wylatti Resource Management of Covelo is the Contractor at the puzzling small project at Wages Creek.

Blues Beach is being done by Myers and Sons, which took on a challenge nobody else wanted- as usual.

Myers and Sons motto is “We Deliver on the Impossible” They have taken on and completed a dozen other emergency projects but according to workers, none as remote, scenic or as daunting as this challenge. So far the company and its famous/infamous predecessor company has met all the impossible challenges, even when newspapers and rivals publicly predicted the hubris of Myers would fail.

They are descended from a man known both as the king of get ‘er done construction men and the cowboy of the trade.

Famously, the late founder C.C Myers underbid rivals by millions and faced likely bankruptcy from his low bid if he did not fix the crucial Interstate 580 overpass in Oakland that burned to the ground when a tanker truck flipped over in the mid 2010s, leaving the Bay Area in a critical traffic panic. Myers banked on completing the project ahead of schedule and earning a $5 million bonus for doing that. The entire scheme was called reckless and ridiculous by rivals and some in the construction media but Myers completed the project much faster than Caltrans or anyone else had deemed possible. Myers did a similar city save after the Northridge earthquake. The C.C Myers company eventually went bankrupt, C.C Myers died and that entity no longer exists. But Myers and Sons calls C.C Myers their founder and has the motto “We do the impossible” The company has completed more emergency projects and on time than any other in the state. They no longer underbid and are not cheap or gambling on huge bonuses.