No Public Portal: Flock System Lacks Promised Access by Fort Bragg Police

Surveillance Sparks Social Media Storm Ahead of Tonight’s Council Meeting

People are freaking out about Flock in Fort Bragg— and that freak out Echoes Far Beyond the Coast.

“Has anyone else seen the flyers on bulletin boards in downtown Fort Bragg about the Flock surveillance cameras? They caught my eye and I started looking into it and holy smokes. These cameras are sinister and are gathering SO MUCH info on us,” wrote someone identifying herself as “Amy” on the MCN listservs.

Police and Flock Safety say the cameras only collect license plate data—and have flagged car theft suspects passing through Fort Bragg at least twice.

Honda stolen in Ukiah recovered

This article raises urgent questions about local surveillance—questions we hope will get answers and we will have a follow up article .

Nationwide, scrutiny of police surveillance has intensified, especially as law enforcement budgets and technologies have expanded under President Trump.

Oddly, there’s been no local outcry over Fort Bragg’s cruiser-mounted Axon cameras—designed to record faces—despite public concern over Flock’s license plate readers, which don’t.

Flock’s visibility in the news may be backfiring. The brand’s prominence has made it a lightning rod for public anxiety, while quieter systems escape notice.

Across the country, Flock cameras are generating a growing list of unanswered questions—about data access, misuse, and public understanding. Investigations by the few journalists still working these beats have uncovered troubling patterns: misrepresented data, intentional misuse by departments, or widespread confusion about what surveillance actually entails.

But here in Fort Bragg, one question stands out:

Where is the promised Flock transparency portal?

When the City of Fort Bragg purchased seven Flock cameras in 2023, then–Police Chief Neil Cervenka promised a public transparency portal on the city’s website—one that would show residents exactly how the cameras were being used. He assured the public that Flock data couldn’t be accessed without cause, and that every use would generate an audit trail available for public review.

That portal was never installed—neither on the FBPD website nor its Facebook page—despite other departments across the country successfully launching similar portals with Flock. If we missed it, please tell us but we had four other people look with no luck and its not on the lists of all the other cities with portals.

“There’s a transparency portal that Flock has developed that we can link on our website,” Cervenka told the Public Safety Committee in 2022. “We can put all of the data out for the public, and they can see how many times we accessed it, and clearance rates.”

He added: “Since we are doing this as public and open as possible, we are going to have a portal on our website… We’re gonna let the public know that we have these license plate reader cameras to hopefully deter crime from coming into this community, committing crimes in our town, and then leaving. The footage is never sold by Flock. We own it, and again, it’s deleted after 30 days. It takes a human bias out. It’s stored in the Amazon server, in the government cloud, which is the highest encryption value.”

Now, controversy has deepened after Flock and Amazon’s Ring agreed to share information about Ring users—though users can supposedly opt out. The promise of transparency feels increasingly fragile.

Amazon, Flock team up to share user data with law enforceement

In cities where public portals were installed, some are now revealing troubling patterns of Flock data misuse.

Flock’s transparency tools have landed law enforcement agencies in hot water—most recently in Humboldt County, where the Lost Coast Observer compared the Humboldt County Sheriff’s actual use of Flock data with the promises made when the cameras were purchased.

Lost Coast Observer story plus late response from the sheirff now included

Earlier in the year, the Eureka City Council voted to ban Flock license plate readers that had already been ordered.

Eureka, Calif., Votes No on License Plate Reader Cameras

Ukiah is among the cities that delivered what Fort Bragg promised—and never implemented.

With 14 Flock cameras in operation, Ukiah maintains a public “transparency page” where residents can view usage statistics and departmental guidelines: Info about the Ukiah portal

The controversy exploded like a bomb, as happens with seemingly every issue in 2025. Like so many issues this year, the backlash was swift and facts were often confused, misrepresented and incomplete.

No public objections were raised when Chief Neil Cervenka outlined plans for Flock cameras at a December 2022 Public Safety Committee meeting, nor at the 2023 City Council meeting where the purchase was quietly approved as part of the consent agenda.

Anyone watching that 2022 meeting might have expected the city to engage the public more proactively. Failing to do so, Safety Committee Chair Councilmember Lindy Peters warned at the time, could trigger a “retroactive social media backlash.”.

The backlash has arrived—late, but loud. Now the city faces a long list of questions it must answer to restore public trust and move forward.

Critics raise valid concerns, but it’s also true that this data has proven useful in solving crimes and protecting communities. A compromise is overdue.

It starts with opening the promised transparency portal—and making a far greater effort to explain how personal information is not being shared, sold, or misused.

The city erred by not scheduling a public comment period before purchasing the Flock cameras. While it’s legally allowed to approve equipment this way, it shouldn’t have. A public discussion should have been held—and the item should have been listed as a discussion item, not buried in the consent agenda.

We found only two relevant meetings: the 2022 Public Safety Committee meeting, where Chief Cervenka presented the plan (with public comment being given but no public objections), and the 2023 City Council meeting, where the purchase was approved unanimously as part of the consent calendar.

The city still has an opportunity to course-correct—by placing this issue on the agenda and dedicating a full meeting to its approach to surveillance. That includes not just Flock cameras, but the full spectrum of technologies now available, from gunshot detectors to cell phone trackers. Are they used here? Will they be?

It’s time for transparency. That starts with finally launching the promised public portal.be? The city must also belatedly put up that promised portal.

Fort Bragg remains the only local public entity that still understands what public engagement means—and often does it well, even if it missed the mark on this issue.

Other agencies once prioritized public dialogue too, but without a local newspaper playing watchdog and connector, that culture has eroded. The biggest challenge now? Communication bandwidth is flooded—by AI-driven news sites and outlets that simply echo official narratives. The result is a media landscape so dull and deferential that readers tune out entirely.

Then, when governments do need to communicate something important—or need someone who actually does the research—they’re drowned out by press-release journalism and platforms more interested in currying favor than informing the public.

Back in 2022, Chief Cervenka outlined the city’s plan for Flock cameras. In 2023, Fort Bragg agreed to spend $48,000 on the system, with payment and installation scheduled over a two-year period.

It ended up taking a bit longer than that.

Cervenka’s presentation (a Flock representative also helped)

In his 2022 presentation—joined by a Flock representative—Chief Cervenka emphasized that the system was not facial recognition technology.

“There are other camera systems that do facial recognition,” he said. “This is not it. This is not Big Brother. It’s not tied to any personally identifiable information. It doesn’t check your name, it doesn’t verify whether the registered owner is a licensed driver. It doesn’t do any of that.”

He added that the cameras aren’t used for traffic enforcement, can’t detect DUIs, and that all data is automatically deleted after 30 days: “We’re not keeping data on people indefinitely.”

Chief Cervenka said multiple times that two Flock cameras would be installed in partnership with PG&E at their substation near Grove and Walnut. We’ll be checking to see if those are in place.

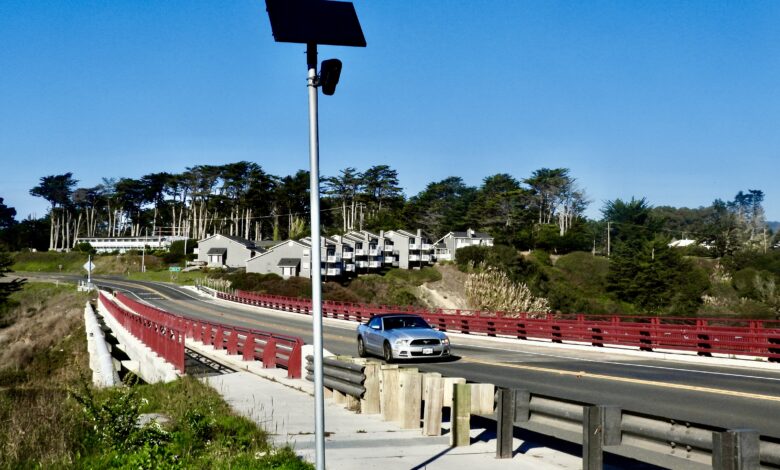

The other cameras are located at South Harbor Drive and Highway 20, two on the Noyo Bridge (it’s too wide for just one), and one positioned southward toward the Noyo River Bridge.

But what about the Axon cameras—and all the other surveillance tech quietly in play? Why is public outrage focused solely on Flock?

It’s a fair question. Axon’s cruiser-mounted cameras are designed to record faces. Other tools, from cell phone trackers to predictive policing software, are already reshaping how law enforcement operates.

Flock may be the lightning rod, but it’s far from the only system raising questions. It’s time the conversation widened.

In January, the Fort Bragg City Council approved spending nearly three times as much on Axon cameras—mounted on police cruisers—as it did on Flock’s fixed license plate readers.

Unlike Flock, Axon cameras aren’t stationary. They record everyone they see—faces included—as officers drive through town. Chief Cervenka described the system as capable of scanning every license plate in a parking lot and performing facial recognition on individuals. Flock cameras are not designed to do that.

FBPD chose Axon in part because the department already uses Axon body cameras, which similarly capture full visual records of everyone officers encounter.

How is this data being used? That question remains unanswered.

So where’s the boundary that protects bystanders from being profiled—whether by a body camera, a cruiser-mounted Axon system, or a fixed Flock camera?

Fixed cameras record every license plate of every vehicle coming and going. That means countless people, not suspected of anything, have their movements logged. The data is held for 30 days, then deleted—but the privacy intrusion, however small, is real.

What safeguards exist to prevent profiling? What oversight ensures these tools aren’t quietly expanding their reach beyond their stated purpose? How is the information secured? What. is the training for officers who might not be used to this approach?

These are the questions the public deserves answers to—before surveillance becomes the default setting.

Why is the Fort Bragg Police Department keeping information on people who haven’t been accused of any crime?

That’s the core question—and one the public deserves a clear answer to. If surveillance tools are capturing data on everyone by default, what safeguards exist to prevent misuse, profiling, or mission creep?

Transparency isn’t optional. It’s overdue.

In some cities, Flock data has been integrated into predictive policing programs—where everyone’s movements are tracked and analyzed, often in partnership with private surveillance firms. We don’t want that here.

It’s a fair concern. One question we hope to ask Police Chief Eric Swift is this: How can we be sure the Flock system won’t evolve into something far more intrusive than what Chief Cervenka described to the Council back in 2022?

The public deserves clear boundaries—and real oversight—before surveillance quietly expands beyond its original promise.

Or am I wrong—is it really no big deal to track people who haven’t been accused of a crime? Are we all fair game to be entered into the system?

That’s the uncomfortable question at the heart of predictive policing. And it deserves more than silence or spin.

Let’s move on to the bumper-mounted Axon cameras. Unlike fixed Flock cameras, they don’t capture everyone entering town—they record only what the officer sees while patrolling.

So let’s play devil’s advocate: Fort Bragg residents hire police to keep the community safe. Our officers know this town. Many can recognize hundreds of local residents, recall past encounters, and make informed assessments—often faster and more accurately than any AI system.

The question isn’t whether officers should observe. It’s how technology changes the nature of that observation—and what boundaries we’re willing to draw.

So are bumper-mounted cameras just cops with supercharged eyes—and a brain trained on hundreds of millions of faces, not just a few hundred locals?

Are they simply feeding that data to seasoned officers, who then make the real decisions about who to pursue?

Or are we outsourcing judgment to machines, one scan at a time?

The problem is, police officers are human. Their brains may hold fewer gigabytes than a computer—but unlike a hard drive, they can’t be accessed by another machine. At least, not yet.

More importantly, human officers store their brains on their pillows. But where does all the data gathered by our AI-enhanced cops get stored? Who has access? How is it secured?

These aren’t just technical questions—they’re civic ones. And they deserve real answers.

There are currently no publicly documented protocols in Fort Bragg that explicitly prevent vendors from reselling AI surveillance data. This lack of clarity raises serious questions about data ownership, vendor accountability, and long-term privacy protections.

While Fort Bragg has invested in surveillance technologies like Flock and Axon, there’s no evidence of formal, local policies that govern how vendors handle or protect the data they collect. According to the Atlas of Surveillance, Fort Bragg has used Axon body-worn cameras since 2016, and more recently adopted cloud-based surveillance systems with AI capabilities. These systems often rely on third-party vendors who store data on remote servers—sometimes in government-grade clouds, as Chief Cervenka noted—but the terms of data use, resale, or integration with other systems are rarely made public.

This matters because AI surveillance systems can potentially be trained on data collected from everyday residents, even those not suspected of any crime. Without strong local oversight, vendors could theoretically repurpose or monetize that data, especially if contracts don’t explicitly prohibit it.

Nationally, agencies like CISA have published best practices for securing AI data, emphasizing the need for transparency, encryption, and strict access controls. But those are guidelines—not enforceable local laws or vendor contracts.

So yes, police officers don’t sell their brains. But when AI systems record, store, and analyze what those officers see, we need to ask: who owns that digital memory? And who’s profiting from it?

If Fort Bragg wants to lead on transparency, it should:

Ensure vendors are contractually barred from reselling or repurposing local data

Publish its vendor contracts and data-sharing policies

Launch the promised Flock transparency portal

Hold a public forum on surveillance tech and data ethics

Another question worth asking: Are we training skilled, dedicated police officers—something I can personally vouch for—only to sideline their judgment in favor of machines?

If human experience and intuition are being replaced by automated scans and algorithmic flags, what are we really gaining—and what are we losing?

Let’s say I have a warrant because I forgot to pay a fine. Do I want to be flagged and arrested by a computer—one that has no judgment, no context, and no sense of proportionality? A human officer might just tell me to smarten up and pay the stupid fine. No database entry. No escalation.

But when machines make the call, nuance disappears.

And if the government has computers smart enough to track my every move, can I still criticize that government without fear? That’s not a hypothetical—it’s a civic alarm.

President Trump is openly using state power to target Democrats, universities, entertainers, and businesses that challenge his anti-DEI stance. When surveillance expands and dissent is punished, what happens to the line between public safety and political control?

These aren’t just tech questions. They’re democracy questions.

Joshua Daniels was among those urging residents to speak up and make the Flock camera issue visible—especially on social media and the MCN listserve.

“Considering the local interest and concern over Flock cameras, I would definitely write your Fort Bragg council member and perhaps attend the next council meeting to comment,” Daniels said. “Regardless of what happens with Flock, there will always be another worrisome project down the road. That’s why a standing commission to monitor this stuff is so critical.”

Back in 2022, Chief Cervenka offered reassurances about how Flock camera data would be accessed and audited. If Interim Police Chief Swift can publicly reaffirm this policy, it could go a long way toward rebuilding trust.

“There’s a search reason required, and it creates an audit trail when we do that search, and in our policy, it’s going to require supervisor approval to do that search. So officers can’t just be out at three o’clock in the morning and checking plates to see where they hit they have they have to have a reason. It’s going to have to be tied to some incident number for them to use it, and we’ll be able to see everybody that accesses the system, and that’s part of the audit that we’ll do for transparency.”

Another big question: Do the same safeguards Cervenka described for Flock cameras apply to Axon systems?

Specifically—what about bystanders and people in parking lots whose license plates and faces are recorded by Axon’s cruiser-mounted cameras? Can any officer access that footage? How is it stored, and who else can see it?

Unlike Flock, which requires a search reason, supervisor approval, and an audit trail, Axon’s access protocols are less transparent at the local level. According to Axon’s own policy templates, it’s up to each agency to define its own rules for data access, retention, and sharing. That means Fort Bragg PD sets the terms—but those terms haven’t been made public.

Axon’s systems can be configured to livestream, geolocate officers, and share footage across agencies. They also allow for centralized evidence management, meaning data from body and vehicle cameras can be uploaded to cloud platforms like Axon Evidence. But without clear local policy, it’s unclear who can access that data, how long it’s retained, or whether it can be shared with other jurisdictions or federal agencies.

If Flock requires an incident number and supervisor sign-off, shouldn’t Axon be held to the same—or stricter—standards, given its broader scope and facial recognition capabilities?

These are the kinds of questions that demand public answers. Because when surveillance tools are this powerful, silence isn’t just a policy gap—it’s a civic risk.

Swift may find himself swiftly put on the spot in his new role. By midweek, he’d already heard the buzz—and addressed it at Wednesday’s meeting of the Fort Bragg City Council’s Public Safety Subcommittee.

“Someone in the public asked a question over the (previous) weekend, and I just wanted to put it out there. They asked a question about AI flock cameras, and I just wanted to be very clear that we don’t have the AI flock cameras. We do have Flock cameras, but what they focus on is the license plate or the description of the vehicle that’s tied to a crime. That’s what we focus on. We don’t collect any facial or pictures of people. We don’t. We keep the data for 30 days, and then it automatically deletes.”

Many departments have opted for shorter retention periods when it comes to data on people not suspected of any crime.

It’s a recognition that just because technology can store everything doesn’t mean it should.

We at MendocinoCoast.news have an interview scheduled with Interim Police Chief Eric Swift later this week, where he’ll have the opportunity to respond to all our questions—including the full list at the end of this article.

The issue has snowballed on social media—especially the MCN Listserve—where more than 20 voices have joined the chorus, calling for answers now. In several cases, residents are demanding that Fort Bragg remove the cameras altogether.

We’ll bring those concerns, along with questions raised at tonight’s council meeting and throughout this article, to our scheduled interview with Interim Chief Swift. A follow-up story will share what we learn.

We plan to speak with Flock once the current rush settles. The company has faced a wave of allegations we intend to ask about—directly and in detail.

An investigation by one of California’s few remaining neutral news outlets uncovered serious issues that Fort Bragg Police Department should be willing to address.

Specifically:California police are illegally sharing license plate data with ICE and Border Patrol

If Fort Bragg is using similar systems, residents deserve to know exactly how that data is handled—and whether any federal agencies are in the loop. Transparency isn’t just a best practice. It’s a public trust

This technology also offers real benefits—ones that shouldn’t be dismissed by a crowd that, so far, hasn’t shown much interest in facts or research.

And the rest of us? We have every right to push back when critics pontificate without engaging the evidence or acknowledging how these tools might actually serve the public good.

Debate is healthy. But it has to be honest.

Back in 2022, Chief Cervenka offered another rationale for installing Flock’s fixed cameras—adding to the case for their use.

It wasn’t just about crime prevention. It was about creating a searchable, auditable system that could be tied to specific incidents, with oversight baked in.

“We get a lot of calls from people outside the area saying my grandpa wanted to take a drive up the coast, and I haven’t heard from them in two weeks. So we’ll be able to check that license plate in the in the database to see if it went past our cameras. If it didn’t go past the cameras, we know they didn’t come through Fort. Bragg, if we see the car come in on, you know, southbound across the Noyo bridge, and then we see them exit town northbound on the footing Creek Bridge and never come back into town, we know that the search can start north of Fort. Bragg, it greatly reduces the search for those missing vulnerable people, and can greatly aid law enforcement in finding those folks, and it importantly, adheres to all state laws.”

This is not just a tech story. It’s a community story.

From audit trails to access protocols, from bystander privacy to federal data sharing, the questions surrounding Flock and Axon surveillance systems are not abstract—they’re local. They touch every parking lot, every license plate, every moment of public life in Fort Bragg.

And while some voices call for removal, others urge reform. What unites them is the demand for transparency, oversight, and accountability.

Tonight’s Fort Bragg City Council meeting is not just another agenda item. It’s a chance to show up, speak out, and ask the hard questions. Whether you’re concerned about civil liberties, public safety, or the future of AI in small-town governance—your voice matters.

We’ll be there. We’ll bring your questions to Interim Chief Swift. And we’ll follow up with what we learn.

Because surveillance isn’t just about what’s being watched. It’s about who’s watching the watchers—and whether we, as a community, are ready to lead that conversation.

Stay tuned. Stay engaged. And stay loud.

While the law generally says there’s no reasonable expectation of privacy for stuff you do out in public, courts are waking up to the fact that continuous, connected surveillance—tracking your every move across multiple cameras over time—feels like stalking and is a serious invasion of privacy. The Supreme Court’s Carpenter ruling even said long-term location tracking needs a warrant because it digs way too deep into your life. Flock’s whole deal? Law enforcement can punch in your license plate and instantly get a nationwide, timestamped history of everywhere your car’s been—mass warrant-less surveillance of everyone, all the time. And who else besides cops gets the data? AI? Anyone with deep pockets? Palantir? We do not really know. Sure, local data deletes after 30 days, but what about nightly backups and partnership copies? Given that selling targeted ads is a prime game of the largest search engine in the world, it seems way too juicy for these captures not to be secretly retained or sold on the sly. Privacy—it’s a key human right that keeps us all relatively safe. We’re absolutely not ready for the Star Trek future where you just ask the computer “Where’s Jim?” and it tells you. While Flock can help police find missing people or stolen cars, I think the privacy of the many outweighs that, especially since a “Be on the lookout!” over the radio still works. I’d vote to yank all Flock cameras down immediately, interesting idea on paper, bad idea for what’s left of a free country in practice.

This is high tech data brokerage. The cameras are secondary to flocks business model. They sell data that stalks our every move. The cops are treating this like social media for stalking, the departments they share their data with are their friends list. Apparently the public is not on their friends list. Detailed descriptions of everybodys travel habits. Imagine what you could do with this kind of power if you had political opponents you needed to make disappear. Or if you just wanted to find hot blondes in your neighborhood. This spy network showed up overnight under the Biden administration. Now the keys to all of our wear abouts are in Trump led ICE’s hands. Communities are standing up against this all across the u.s. We have to act before it is too late and we all die at the hands of Orange Pinochet. https://youtu.be/95zqRm8vrKk