Makela Bros to be Reborn: Urchin Farm planned, Ice House has new incarnation, Handmade Meets Tech-we need both!

John Henry Leaves Noyo Harbor, But His Legacy Stays Anchored

John Henry is finally leaving Noyo Harbor. What he built there—what he stood for—won’t be forgotten. So much of it is still standing, still working, still fishing.

Makela Brothers and Howard Makela were among Fort Bragg’s own John Henrys: hands-on builders of legacy, labor, and local pride. The business they shaped became one of the coast’s most beloved icons—revered by the art world, respected by the working world. They were legends, and they are mostly all gone, but some sons and daughters remember and carry on.

“John Henry” isn’t just folklore. He’s the mythic everyman who swung harder than the machines, who stood tall against cheap imports and corporate erasure. But in today’s tide of globalism and AI, that kind of grit is harder to find—and easier to forget.

Not here. Not yet.

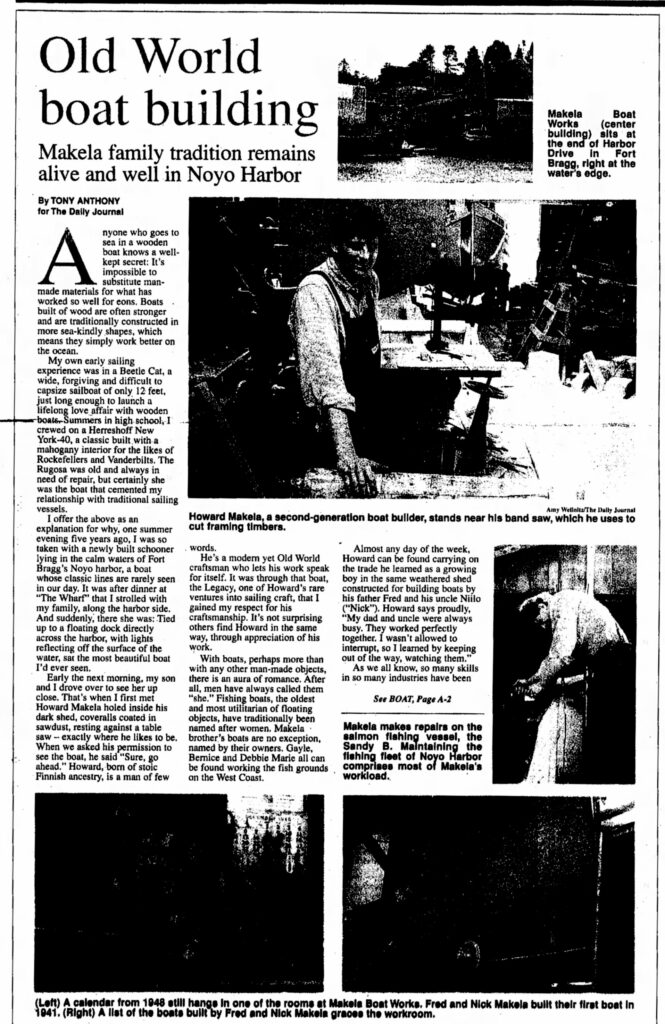

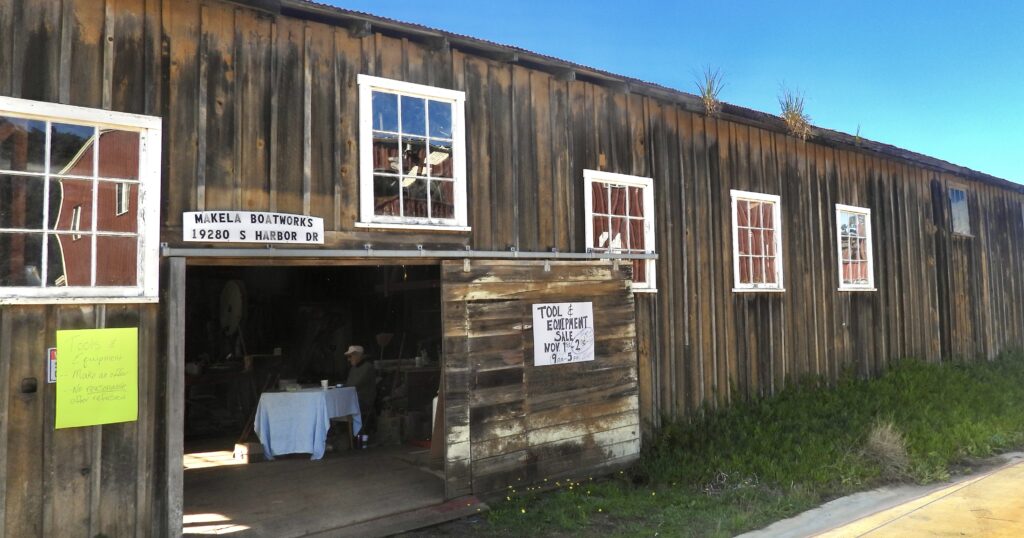

On Saturday, Makela Boat Works Held a Yard Sale—And a Living Tribute

Two Makela women ran the show, descendants of the family whose parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents built a Noyo Harbor icon—starting with a shop that literally opened out onto the water. The sale wasn’t just about tools and treasures. It was a quiet celebration of a legacy still standing, still working, still woven into the harbor’s bones.

The Makelas weren’t luddities—plenty of power tools were in the mix..

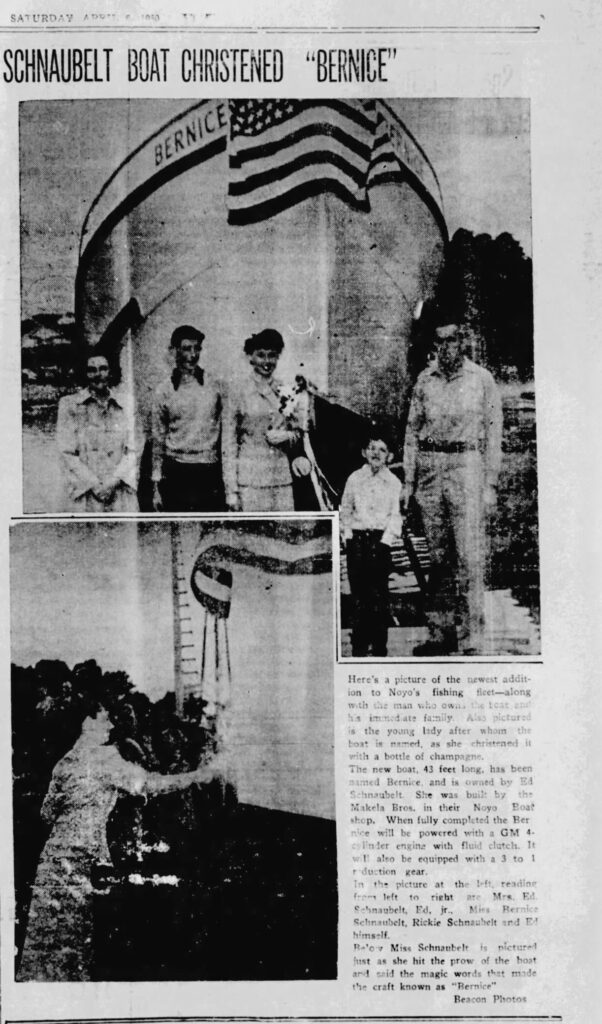

The family is willing to continue the sale by appointment. Fred and Nick Makela founded the boat shop after World War II,

building it by hand and by heart.

After WWII, the Makela Brothers Picked Up Where They Left Off

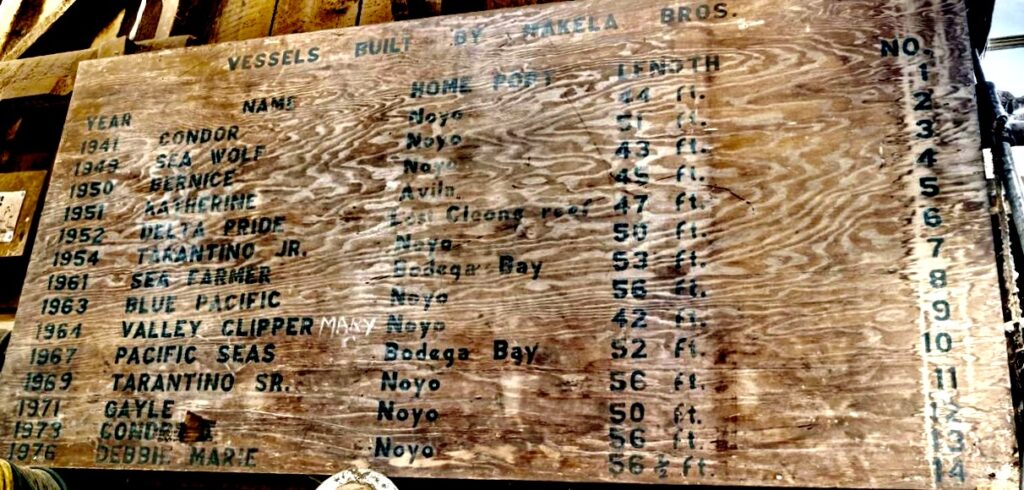

Fresh from the war, the Makela Brothers returned to a dream they’d barely begun in 1940. Straight out of high school, they built their first boat—the 44-foot Condor—completing it in 1941, just before bombs fell on Pearl Harbor. The war interrupted their plans, but not their purpose. When they came home, they got back to work, shaping a legacy that still floats in Fort Bragg’s memory.

In 1947, the Makela Brothers Launched a Legacy in Wood and Salt Air

Makela Boat Works began in 1947-8, built by the brothers, their children, grandchildren, and a crew of local apprentices and employees. They crafted fishing boats by hand—never rushing for profit, never cutting corners. Every plank, every weld, every curve was shaped with care, no matter how long it took.

With their own hands, they joined thousands of small-town craftsmen in building an American economy rooted in labor, not leverage—an economy strong enough to help rebuild a war-shattered Europe and Asia, still tangled in the grip of inherited wealth and concentrated power.

A Legacy Built Slowly, Lasting Strong

The Makelas built just 14 boats in their entire history—a number that would make a modern profit-chaser wince, but which delighted their buyers. Each vessel was made right, built to last. Over the years, they also repaired countless others, keeping the harbor’s fleet afloat with skill and care.

Howard Makela took the helm and ran the business until 2024. On March 29, he tragically died at age 68 after an accident while working on the Gayle (also known as Moriah Lee), a Makela Bros.–built boat, in Noyo Harbor.

With Howard gone, the family made the difficult decision to sell the building. But the legacy—hand-built boats, generational craftsmanship, and a harbor shaped by care—remains.

Makela Boat Works is in escrow, pending sale to a company planning to turn the riverfront boat shop into a sea urchin farm. The listing shows a price north of $600,000, though the final amount remains undisclosed. (And yes, escrows sometimes fall apart—this one’s still in motion.)

But the real story isn’t just real estate. It’s about the Makelas, the legacy they built, and the evolving face of Noyo Harbor. The next chapter will dive deeper into the new buyer, the vision ahead, and how old bones might support new tides.

Stay tuned.

19280 S Harbor Dr, Fort Bragg, CA 95437 | Compass

it’s the echo of a Mendocino craftsman’s hand

Blue Economy Rising: From Boatworks to Icehouse, Noyo Harbor Evolves

We’ll report more soon on the history of Makela Boat Works and the new buyer behind its next chapter. But this isn’t a sad goodbye. The building is being repurposed into a “Blue Economy” hub—a vision for local jobs and ocean-minded innovation, as tuned to the tides as any Makela-built boat.

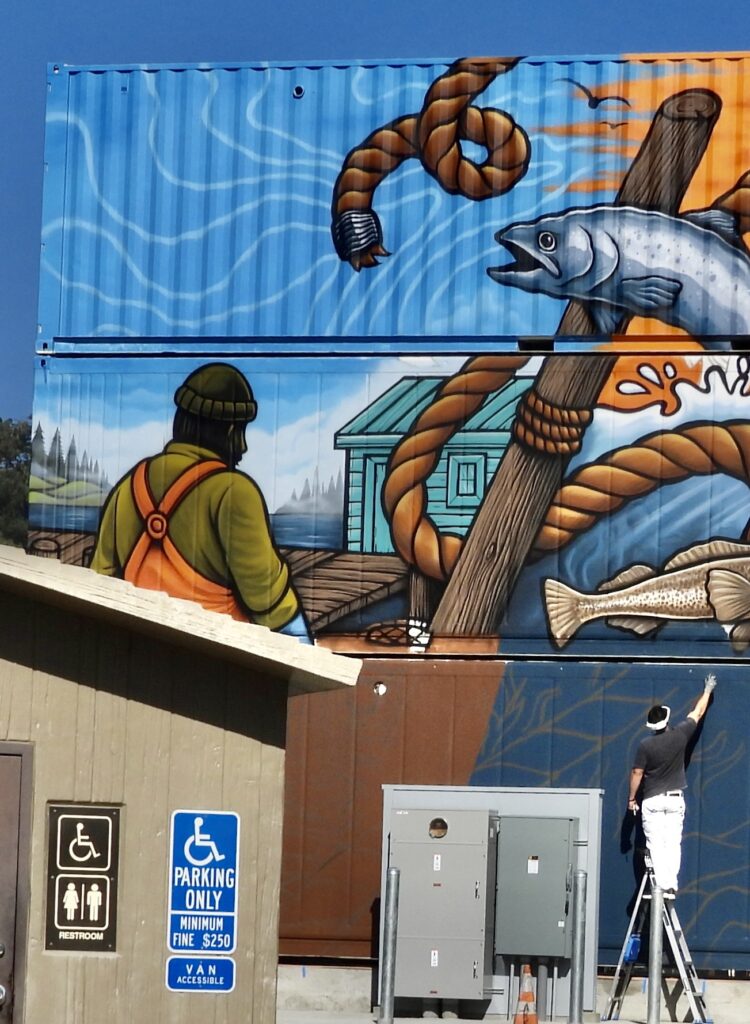

Just a throw from shallow left to home plate away, another Blue Economy effort is already taking shape. Muralist Vinnie Schraner was spotted finishing a vibrant piece on the new Fort Bragg icehouse, right next to the Noyo Harbor District office. The icehouse itself is a feat of creative reuse: three massive shipping containers—likely once stuffed with cheap global goods—now reimagined to produce 20 tons of ice for local fishing boats.

Jeff, owner of Fort Bragg’s Akeff Construction, admired the work as crews secured the precarious-looking tower of metal. It’s a structure born from global detritus, rebuilt for local resilience.

“This is never going anywhere with the weight up there and the job we did anchoring it down.” While some of us were having nostalgic Luddite moments after seeing Makela’s yard sale, not artist Vinnie.

Vinnie provides a full video journey that is definitely worth watching.

Breathtaking Noyo Harbor Ice House Mural Takes Shape

Virtual Vision, Real Ice, and the Return of Local Power

Muralist Vinnie Schraner showed off the headset he used to paint the new icehouse mural. “Virtual reality” isn’t quite the right term—it’s more like augmented clarity. The headset lets him see the world as it is, while overlaying a stored image of the mural mockup onto the shipping container canvas.

Noyo Harbormaster Anna Neumann, the driving force behind the Blue Economy push radiating from Noyo Harbor up and down the coast, demonstrated how water and electric hookups transformed those containers into a working icehouse. It’s designed to replace the aging icehouse across the harbor—still operating, but under threat of closure for more than a decade.

Like Makela Boat Works, the old icehouse helped power Noyo Harbor’s glory days of fishing. The Blue Economy arrives with press releases and panels; those earlier efforts thrived on word of mouth, with the occasional amazed reporter stumbling in to write a story. Frank Hartzell once watched Howard Makela repairing a boat back in 2005, but that story seems to have vanished. Frank also used the old icehouse for his commercial chicken operation—a tale we meant to tell in the Advocate, but never got around to.

These efforts were windows into a different world—one we believe we desperately need to remember, and maybe even return to. Globalism is faltering. But with initiatives like the Blue Economy, we have a chance to rebuild a small-town economy rooted in local bounty and generational stewardship. If we don’t overdo it—and if we learn to be better environmental caretakers this time—we might just get it right.

We’d do well to follow the example of our Native American neighbors, who lived comfortably off the ocean and forest for 10,000 years without destroying them. Settlers managed to unravel that balance in about 50.

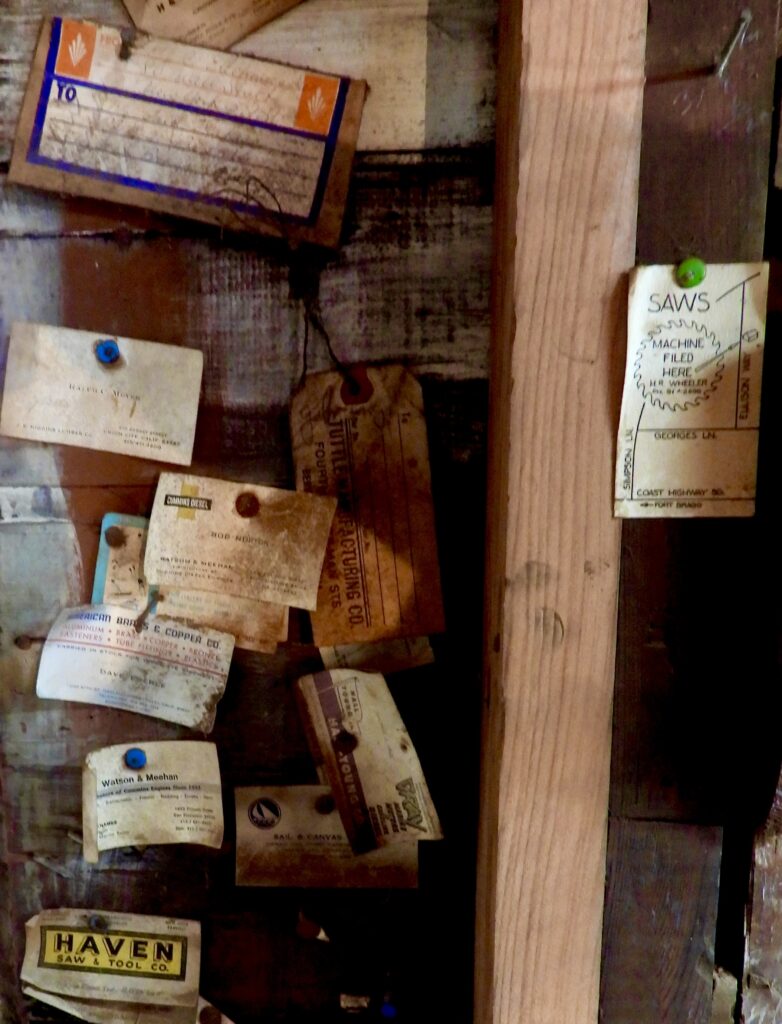

At Makela, Frank and the Dogs Saw the Proof

At Makela Boat Works, Frank and the dogs were struck by the physical evidence that these men were the real-life John Henrys—craftsmen who built with muscle, memory, and pride. The dogs, of course, were more captivated by the smells and the view: gazing up through a roof made from ordinary lumber of its time, now the kind of wood you’d call priceless.

hydraulics to saw sharpening.

Frank’s Hammer and the Legend of Gary

In his hand, Frank held the lightest hammer he’d ever gripped—one that swung with the kind of precision only a craftsman carpenter or boat builder might dream of.

Johnny Cash – The Legend of John Henry’s Hammer (Live In Las Vegas, 1979)

As a young laborer, Frank met another John Henry: a Texas redneck named Gary. Gary could swing a hammer and drive a nail faster than Frank could blink. Frank would hold up a 2×4, and Gary would sink the nails perfectly—one swing, no misses, every time. Meanwhile, Frank bent half the nails or whacked his own finger. It was exhausting just keeping the boards straight for an increasingly impatient Gary.

Other crews on that massive subdivision were using the crude nail guns of the time. Gary didn’t need one. He was faster, better—and revered. His assistants rarely lasted.

The Art of the Hammer

Finally, sweating bullets, Frank got the rhythm of the boards. He and Gary worked all day at a speed that made the other crews stop and stare. Frank knew it mattered—being on the winning team, even if a bench player.

At day’s end, Gary shared a few secrets. Most of it was about balance—yes, the man, but mostly the hammer. A craftsman like Gary, or the Makelas, is never satisfied with a hardware store hammer. They scuff the handle, carve it, tap it with another hammer until it feels right—until it strikes true.

Frank, part gullible kid and part skeptical journalist, thought Gary might be snowing him. So he researched it. Turns out, hammer balance is an engineering puzzle still unsolved, especially in mass production. Sure, there have always been $200 handmade hammers with perfect balance—but Gary and the Makelas wouldn’t buy one. They’d make it better themselves.

Truth is, despite the bravado, they missed sometimes. And yes, balance could be ruined. No computer or AI has ever matched the “feel” of a well-balanced hammer—even in the hands of an amateur like Frank, who once held that magic in Texas.

Years later, Frank found a batch of old Makela hammers for sale. Most were off-kilter. But then he found the grail: the ugliest hammer in the world. Its wooden handle long replaced with melted leather, mystery metals, maybe even lead.

LOL. He’s already dumber.

The Hammer Remains

It’s feather-light and perfectly balanced, long after its masters have gone on to build the great ships of heaven. It’s so ugly, no one would bid a penny on eBay. And yet—it’s priceless.

This is the hammer. The hammer. The one John Henry used to beat the machine. And like in the song—and in our world—he won, then he died.

We must not forget him. In fact, it’s time we brought him back. back.

Check out the Makela boat works page:

https://makelaboatworks.com/

A Nation Built by Hands, Not Hate

Our faltering nation was once great—not in the way it’s mythologized in 2025, but in the way it was built by Americans like the Makelas. These were workers, not haters. They didn’t all look like the Finnish-descended Makela brothers. Most were immigrants. All but the Indigenous people—who were driven from this coast—came from somewhere else. Some arrived by choice. Others, like the white indentured servants of the colonies and the millions of enslaved Africans, were brought by force.

Together, they embodied the promise etched on the Statue of Liberty—a promise now scorned by the American GOP and Frankly, the other party too. These immigrants built our cities, our highways, our bridges. They forged the war machine that helped rescue the world from fascism. Now they are cast aside and we are told this is not a country built by immigrants. I guess the Natives must have done it!

That was greatness. And it didn’t come from slogans. It came from calloused hands, shared purpose, and the belief that building something better was worth the sweat.

Before the War Ended, the Seeds of Globalism Were Sown

Before the war to end fascism was even over, the Bretton Woods Conference took place—arguably the most pivotal economic event in modern history. From it, globalism emerged, enriching the world’s wealthiest and reshaping economies everywhere.

The architects of Bretton Woods blamed fascism on local and national economic failures. But their fiercest critic, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, warned both parties that fascism was born of concentrated power and wealth in too few hands. After FDR’s death, the lid flew off Pandora’s Box. Globalism surged forward with little regard for democracy, equality, or local control. Both parties forgot the small town, forgot Made in America and picked automation over craftsmanship as the way forward.

At first, the tidal wave of money globalism created lifted all boats—including the ones built by the Makela Brothers. But the cost of that lift, and who stayed afloat, would become the story of the next century.

Warnings Ignored, Consequences Delivered

FDR’s warnings about restraint—and the prophetic words in the long-ignored pamphlet The Limits to Growth—have come true. Globalism, once hailed as progress, has hollowed out rural economies and paved the way for a new kind of fascism—one far more insidious than anything imaginable before small towns were bankrupted and local power erased. We see it all over the world now.

To the Immigrant Laborers Who Raised Cities and Small Towns

Who was John Henry? He came from everywhere—by choice, by force, by desperation and hope. They laid bricks, poured concrete, framed houses, wired lights, and built the bones of America. Not just the skyscrapers and highways, but the small towns too—the harbors, the diners, the boatyards, the schools.

They were the hands behind the promise. Not the mythologized greatness shouted in slogans, but the quiet, enduring kind: the kind that shows up before dawn, stays until the job is done, and leaves something standing that lasts.

They didn’t all look alike. They weren’t all welcomed. But they built this country. And they deserve to be remembered—not just in history books, but in every bridge we cross, every harbor we fish, every town we call home.

And sometimes, in the grip of a hammer—ugly, feather-light, perfectly balanced long after its masters are gone—we feel them again. Frank held one once. It swung true. It whispered of Gary, of the Makelas, of all the John Henrys who built with heart and never asked for glory.

That hammer, like their legacy, is priceless—and no, you can’t have it for a buck on eBay! It’s mine.

A scissors lift will help him reach the final strokes on the three-story canvas.