Massive Caltrans construction underway in Westport—among the largest of its kind in California—has not, to date, compromised the health of nearby Chadbourne Creek in any observable way.

In a flicker of color and a tiny splash no bigger than a raindrop, the young gamefish spun, darted, and—just for a moment—revealed herself in Chadbourne Creek

This fierce little shimmer of gold wasn’t fazed by the towering construction crane looming above her—part of the massive Myers Construction/Caltrans site. Instead, she slipped beneath one of its gigantic boulders, taking refuge from the photographer’s lens. She and her siblings, all likely under a year old, were living proof of resilience—a perfect picture of the Coast’s beloved oceangoing fish making their comeback, despite 150 years of human onslaught.

First of it’s kind Tribal Collective Awaits “Impossible” State Route 1 Fix Before Taking Ownership of Blues Beach

At what’s left of Blues Beach, just north of Fort Bragg, one of the largest Caltrans projects in Northern California history is now underway. We came to monitor the work—and to check on the migratory fish still struggling to survive in our region. In a creek once wiped clean off the map by unrestrained 19th-century logging, there they were: flashing by the dozens, bright and quick as when the settlers first arrived.

After decades of work, Coho salmon are surging again along the Mendocino Coast. In 2024, an estimated 15,000 silver—or Coho—salmon returned to the rivers and creeks of the county, from the Garcia River to Usal Creek in the Usal wilderness. Steelhead numbers haven’t yet shown meaningful recovery. Chinook, or king salmon, counts remain lower than Coho. Although the DFW monitors chinook or king salmon through spawning surveys in the Mendocino coastal streams, the kings play second fiddle to the silvers in our county streams.. They are not as prevalent as the other two species -annual estimates have ranged from zero up a high of ~1000 since we have been monitoring. DFW told me their sampling design might not cover all of their habitat so they think they may be underestimating them some years. Outside of the Mendocino coast to the north in the Eel and Klamath ( and in the central’s valley of ca) they heavily monitored of course. The kings are the only California-caught fish of the three one will ever eat at a local restaurant.

Around here, salmon recovery efforts are focused squarely on Coho.

A second two-day ocean salmon fishing season opens this Saturday—but only for areas south of Point Reyes in Marin County, just north of San Francisco. Ocean Salmon Fishery Information, The limited window applies solely to Chinook salmon, which are in deep trouble in the Klamath River system to the north—prompting the closure of Fort Bragg’s fishery.

Coho salmon face the opposite challenge: they’re struggling south of Fort Bragg but remain more stable to the north. Understanding the difference between Mendocino’s two primary oceangoing freshwater fish—the no-ocean-fishing Coho and the occasionally ocean-accessible Chinook—is essential. It not only helps anglers avoid steep fines, but also underscores how fragile and degraded our coastal rivers and streams became before restoration efforts began.

Yet there’s a glimmer of hope. Restoration efforts over the past two years have sparked a resurgence in Central Coast Coho. Numbers remain below recovery targets, but optimism is rising—more than we’ve seen in years. (DFW map)

The 2024 spawning season brought the highest number of Coho we’ve ever recorded on the Ten Mile River—surpassing NOAA’s fisheries recovery target from last year. That was really exciting,” said Sarah Gallagher, senior environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s coastal fisheries program.

Make no mistake—wild salmon and steelhead remain at long-term risk of extinction. But these recent gains have sparked real hope among many.

The Idaho Statesman has written in depth about the science that shows these great fish could be lost.

Hope is growing here. You can walk into the forests and witness fish returning, carried back by the latest textbook salmon restoration methods. And yet, nothing about this story has followed a script—certainly not a textbook. Every river and stream tells a living tale of ferocious competition, and now and then, unexpected collaboration among these fierce fish species. Rainbow trout have expanded their range exponentially across California—and far beyond. But hatchery trout and wild trout are vastly different creatures. And no one knows why one will become a steelhead, while her brother will not. Steelhead fishing is thriving in many inland waters, but it’s never been allowed—and likely never will be—in the ocean.

This article draws from studies, reports, and conversations with three biologists. Sarah Gallagher, based in Noyo Harbor, provided key insights on the fish. Earlier this year, we spent over an hour tracing the arc of the salmon comeback, as Gallagher led a tour of restoration efforts deep in Jackson State Forest—near the old egg take station—organized for Assemblymember Chris Rogers.

MendocinoCoast.News has been visiting daily the busiest industrial zone in Mendocino County—Blues Beach—watching the mesmerizing pace of work unfold from the bluff and the sand. We’ve spoken with biological and tribal monitors. Because the state has declared this construction an emergency—part of a desperate bid to rescue State Route 1 above—it must continue, environmental challenges or not. The highway is threatening to collapse into the ocean, which would sever Westport from Fort Bragg.

Biological monitors can only watch and record what they see. Anywhere else, they could shut the entire job down. NOT here. The emergency overshadows everything. They told MendocinoCoast.News that the ultimate find in Chadbourne Creek would be a Coho salmon. There was once a run here—but none have been documented since the early 20th century. Chinook likely never reached this creek. The spawning grounds for Coho and steelhead were buried long ago under mud runoff from logging. And to add further insult, a railroad track was laid right up the creek. And yet—there it was. A pool full of fish. Either steelhead or Coho. As smolts, Coho and trout are nearly indistinguishable.

Which was it? We had to find out.

Modern logging is more mindful, with restorationists working alongside timber companies to heal the land. Still, the damage left behind by a century of unchecked logging lingers in the soil, the streams, and the stories.

Not since the logging days over a century ago has anything been built on a Mendocino County beach quite like what Caltrans and Myers Construction have erected at Blues Beach—in just a matter of weeks. The site sits north of Ten Mile Bridge and can be glimpsed from a few roadside pullouts, but this massive project—one of the biggest in California right now—could easily be missed by someone just passing through. We had high hopes for a Coho when the digital photos were “developed” back home. If so, it would’ve marked a meaningful scientific find. But after years of trout fishing, we had a gut feeling: this spirit in the water was pure wild California native Rainbow. A closer look at the squared-off tail confirmed it—rainbow trout.

Over the next week, we found more trout—gathered in big schools alongside threespine stickleback, which thrive in both freshwater and saltwater. The trout were vigorous and feisty, darting upstream. Bend over, try to zoom and focus—and whizzzz—they shot into deeper pools before you could blink.

But then the trout came right back down, even with us standing there. Any angler knows that’s usually a sign: something up in the deeper pools spooked them more than the photographer. Eventually, we stood still long enough to get the shots.

The emergency project at Blues Beach has done its best to steer clear of Chadbourne Creek—and our regular visits suggest those efforts are paying off. Despite the activity, dust, and heavy equipment, the creek’s water remains crystal clear and undisturbed, even deep into the brush where we’ve been able to reach. But Mother Nature had her own plans. Sand, waves, and water shifted the creek northward, so it now flows directly beneath the boulders. Those rocks turned out to be perfect shelter for baby trout—ranging from one to two inches long. Gallagher noted they weren’t headed to sea anytime soon, but had been spotted moving freely up and down the river. They used the rocks to hide from predators—like us—and maybe even to lurk in the shadows, waiting on prey. We saw tiny ones, barely half an inch, all the way up to a 2.5-incher. Were they on the beach because they were preparing to head out to sea?

Gallagher said none of them would be heading to sea until next year—and maybe not even then.

“Steelhead show a lot of variation. As juveniles, they can remain in freshwater for one, two, even three years,” Gallagher said.

Gallagher knows a lot about fish—especially the three local ocean-going, freshwater-born sport species. The most numerous in Mendocino County is the Coho, also known as Silver Salmon. Next comes the Steelhead. And last, the Chinook, or King Salmon. She said all three are important to rivers and streams here, just each with a different history.

Coastal chinook have always had lower numbers than Coho or steelhead here.

There are multiple types of each fish. Coho salmon are plentiful in Oregon, and many make their way down to Mendocino County. But California’s native Coho—especially the Central California Coast subspecies—are protected, and critically endangered. These are the fish in our rivers and streams. Out in the ocean, though, Oregon Coho may be swimming alongside their California cousins. That overlap creates confusion—and sometimes frustration—among those who believe Coho are abundant and that fishing should be allowed.

“The 10 Mile River and Noyo River have had some of the highest Coho numbers since we’ve been doing population monitoring, which started in 2009.”

There are differing views on the Navarro River. The Nature Conservancy is among those working to bring the Navarro up to the restoration efforts like Ten Mile and the Noyo River.

While steelhead fishing in the ocean is strictly prohibited, it’s permitted in certain rivers—so long as anglers use barbless hooks and practice catch and release. These rules apply only to rivers known for steelhead migration. In those waters, any trout over 14 inches is presumed to be a steelhead.

Before casting for steelhead, anglers need to check California’s low-flow guidance. If water levels dip too low, fishing gets paused to protect the run.

Case in point: the Eel River, which welcomed rods earlier this year, was shut down on Sept. 1 when flows fell. Want to stay ahead of the curve? You can sign up for alerts when rivers open or close to fishing.

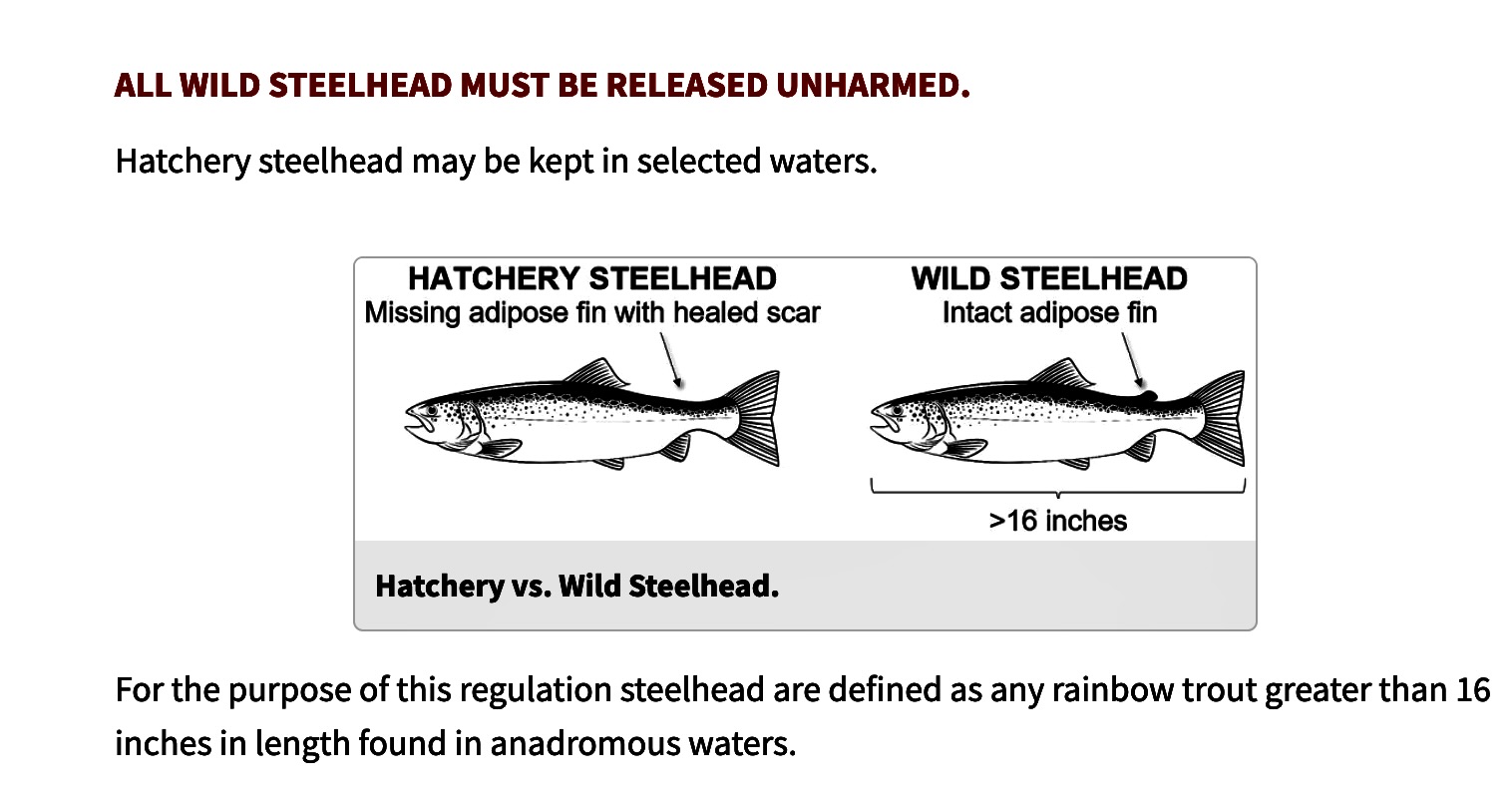

Rainbow trout and steelhead from hatcheries are required to have had their adipose fin removed before they were released from the hatchery. This doesn’t hurt the fish as the fin is mostly a vestigal organ. But there is no way to look at a young fish and tell if it is rainbow or a steelhead- they simply havent “made up their minds” or the switch thrown yet to go to the ocean or not.

Only a necropsy can tell them apart—ocean conditions blur the lines between species.

For the past 15 years, the average coho salmon run hovered around 5,000 fish. But in the last two years, numbers have surged to over 15,000. These are Central California Coho Salmon—Mendocino’s native silver swimmers, once teetering on the brink of extinction. Fishing for coho was halted in the 1990s to protect them, and now, against the odds, they’re returning to the coast they call home.

NOAA recently spotlighted the remarkable comeback of Coho salmon in Mendocino County—a milestone for native fish and local watersheds. This resurgence is more than a win for Coho; it’s a triumph for wild steelhead, too. With hatchery trout rarely found in these rivers, the recovery reflects the strength of truly wild populations reclaiming their home streams.

But what about the steelhead trout numbers ?

Steelhead runs along the Mendocino Coast average around 3,600 fish annually. “Population estimates have reached as high as 9,000,” Gallagher noted, “and over time, steelhead aren’t trailing far behind the Coho.”

We learn in elementary school the epic tale of salmon—migrating far into the ocean, only to return through riffles and rapids, swimming miles upstream to spawn in the very place their parents gave them life.

But the steelhead’s story? Even more bizarre.

All steelhead begin life as rainbow trout. They earn their “first cousin of salmon” status when some decide to leave the comfort of their home stream and head for the ocean.

They do everything salmon do—except one thing. Steelhead don’t all die after spawning. They can, and sometimes do, return to the ocean and come back again another year.

Even more fascinating, Gallagher explains, is what happens when a rainbow trout becomes a steelhead. She might head to the ocean, bulk up to 7 pounds and stretch to 24 inches, complete with that fearsome hooked jaw.

Meanwhile, her sibling—born at the same time—might stay in the river his whole life, growing to just 14 inches. Sleek, soft, and beautiful, he’ll weigh in under 3 pounds.

But when the ocean-going giant returns to spawn, her eggs might be fertilized by another sea-seasoned steelhead—or by that little river-dweller who never left home.

Some of their offspring will stay put as rainbow trout. Others will chase anchovies in the open sea… or become supper for a sea lion or shark.

Is there a more amazing creature than that?

Gallagher painted a fascinating picture out on the stream of how efforts to bring Coho back, such as littering streams with logs. Some rivers get all three. Some streams are favored by coho not steelhead.

“We’ve been tracking steelhead for at least 17 years And they are a little bit more challenging to track partly because of their interesting and varied life history strategy.”

She said steelhead haven’t hit recovery targets yet, but are slowly recovering. And without hatchery rainbow trout to help.

“They’re subject to the same kind of pressures as the salmon from degraded habitats.”

“Some of the smaller watersheds are predominantly steelhead like Usal Creek. A lot of the smaller tributaries (like Chadborne) don’t have currently have coho, but they do have steelhead.

Mendocinocoast.news’ initial instinct about the ferocity of rainbow trout was correct. They actually prefer living in fast water and it fills them full of oxygen and vigor.

“Juvenile Coho tend to like the slower-moving pools,where juvenile steelhead you’ll find more in those riffles. . Both benefit from the increased number of pools; a lot of the restoration work is aimed at getting the river to function like it is supposed to do naturally, taking it back in time to the conditions that existed before. Overall, putting the logs back in the creek creates more pools, more riffles, and more complexity.”

Early environmental regulators were, at times, salmon restoration’s worst enemy. Back then, the Department of Fish and Game (now DFW) insisted timber companies “clean out” creeks and rivers after logging—stripping them of woody debris in the name of good science.

It was the best thinking of the time. But it didn’t help the fish. It hurt them.

Once the damage was understood, it took regulators and grant-makers more than two decades to figure out how to undo the mistake.

When I first heard about putting logs back into streams—funded by grant money, no less—it sounded like pure nonsense. As a member of the Salmon Restoration Association Board, I went along, but I was deeply skeptical when we helped fund one of these projects 15 years ago.

I’ve revisited that stream many times over the years, and I can say with full confidence: it works. The logs transform the flow, carving out a rich, complex habitat that simply didn’t exist before.

This is real salmon and trout restoration. And it’s really working.

Unlike those tidy tales from elementary school, the fish don’t always return to their exact birthplace. If a stream gets too crowded, suddenly a waterway that hasn’t seen migratory fish in 50 years might host a population again.

Too much traffic at the sandbar? The fish will push further upstream.

And that’s a good thing. Salmon and steelhead play a vital role in river ecosystems—feeding bears (and keeping them in the forest instead of your backyard), nourishing other stream and riparian creatures, and restoring balance to habitats that depend on their presence.

The Chinook or King is the truly the monarch of all the world’s sportfish that travel between freshwater birthplaces and ocean sojourns. But Chinook prefer rivers grand enough for their kingly size, such as the Klamath, Eel and Sacramento River systems. Biologists have been tracking the success of restoration efforts as well as learning how each river has its own surprisingly different narrative on the successes and failures of the three migratory fish. Kings rule and the others know it Any angler can tell you that when Coho and Chinook are both offshore the Coho are up close to the boat, ceding the depths with its richer bounty to the Coho. Not that much is known about Chinook in Mendocino County streams and rivers as the giant pink fish literally never fit in most of the relatively dinky streams here. Some years there have been zero reported. Gallagher said as the numbers increase, salmon go further and further up the streams to spawn, to avoid already used areas. Another source said this could be good news for black bears which used to eat much more salmon they found deep in the forest. He said loss of this crucial forest food could be one reason why so many bears now come to town. If salmon and steelhead were to return to the deep forest, perhaps the bears would leave town. (He wouldn’t let me use his name as there is no evidence this is true, but it does sound reasonable.)

There is a real pecking order among the three fish. The kings always have the cool table. When fishermen went out on Fort Bragg’s one day fishing season this year for Chinook, they had to drop their lines through the Coho. The Chinook usually claim the bottom. But there were very, very few Chinook down there. Many, many of the much more prevalent Coho were hooked and had to be released.

This is because the Coho from Southern Oregon are common off the Coast. If that was the only Coho here, fishing could resume. But the endangered Central California Coho also mixes with the ones from Oregon, as do those from local rivers and streams. Fishermen could seriously hurt the comeback of Central California Coho if allowed to catch the plentiful Coho from Oregon.

To make it all even more confusing, there may be hatchery rainbow trout/steelhead in the mix, headed back up the delta. Ocean fishing of steelhead is not allowed because so many come from rivers where they are virtually extinct.

f an angler wants to catch a steelhead, it’s legal in rivers—but only under strict conditions. Ocean fishing for steelhead is completely prohibited.

To retain a river-caught steelhead, anglers must carry a report card and record where and when the fish was caught. And even then, only hatchery steelhead can be kept. Barbless hooks are mandatory.

In Mendocino County, though, river steelhead fishing is mostly a bust. The best rivers—like the Noyo and Ten Mile—have limited access, and there simply aren’t enough fish to justify a special trip.

Steelhead are occasionally caught by fly anglers targeting rainbow trout. But river fishing shuts down when flows drop too low, which means dry years often mean no fishing at all—and closures can vary by season.

Check the river map before you head out—or better yet, ask someone who’s already been skunked. They’ll know where not to cast.

All Coho salmon fishing has been banned in California since the 1990s, when populations originating in the state’s rivers collapsed.

While Oregon’s Coho have rebounded and are now plentiful in the northern part of the state, California’s Central Coast Coho remain endangered.

Because of their protected status, there’s no expectation that ocean Coho fishing will resume in California within the next five years.One of the most in depth views of everything Coho is this Russian River monitoring program.

MendocinoCoast.News will continue to monitor the massive Westport Slide project, led by Caltrans and Myers Construction.

Another great info graphic here on California and its salmon.

and into dark crevices like a seasoned escape artist.

Caltrans provided a summary of what has happened with Chadbourne Creek. From spokesperson Manny Machado:

“There are two jurisdictional water features within the project area: an intermittent stream that is primarily stormwater and drains onto the beach west of the small parking lot at the end of Chadbourne Gulch road, and Chadbourne Gulch, which is a permanent stream that flows east to west and outlets onto Blues Beach. Caltrans worked with the Coastal Commission, CDFW, USACE, NCRWQCB, and NMFS to practice full avoidance of Chadbourne Gulch. In order to construct the turnaround area that was needed for delivery and staging of large rocks for the revetment site, a channel was excavated on the beach to direct the mouth of the stream southward, avoiding the project area while maintaining the stream’s ecological function. We are aware of the steelhead in Chadbourne Gulch and will maintain avoidance throughout the duration of the project. The area is also being monitored by a full time biologist. The intermittent stream that drains onto the beach west of the small parking lot that Frank is referring to is not fish bearing, and is culverted under the turn-around area with two side-by-side 24” diameter steel pipes.”

So far so good. We shall continue our coverage.