Science Meets Shoreline: Kelp Futures: Seaweed Seed Banks, Shore Plantings, and Human Selection – Learn more at North Coast Kelp Festival Oct. 3–6

Fort Bragg, 1875: A Forest Future Unfolds

Imagine a moment when Fort Bragg stood not just at the edge of the Pacific, but on the brink of possibility. In 1875, as the redwoods towered and timber fever gripped the coast, a new kind of forester arrived—not with axes alone, but with ideas. They spoke of selective cutting, seedling stewardship, and forest cycles that could last generations. Their vision? A town empowered by sustainable industry, employed by thoughtful harvest, and enriched by an environment that could endure.

Had we listened then, Fort Bragg might have become a model of ecological foresight—a place where prosperity grew alongside preservation. Instead of clearcuts, corridors of canopy. Instead of boom-and-bust, a legacy of balance.

The Cost of Ignoring the Forest’s Future

Sadly, Fort Bragg’s forefathers didn’t seize the chance. When university scientists and early conservationists offered insights into sustainable forestry, their warnings were dismissed as impractical or naive. The allure of fast profits and endless timber blinded decision-makers to the long game. Within a few short years, clearcutting became the norm, and with it came erosion, habitat loss, and the slow unraveling of a community’s natural wealth.

What could have been a legacy of stewardship became a cautionary tale. The redwoods, once seen as infinite, began to vanish. Jobs followed. Watersheds suffered. And the very environment that had sustained Fort Bragg’s rise began to buckle under the weight of short-term thinking.

Can we do better this time?

We can—and we must.

This time, the forests aren’t the last frontier. Old growth is gone here in Mendo. It’s the towering kelp under the ocean, the shoreline, the ecosystems we long overlooked. We have the science, the community will, and the hindsight of history. We know what happens when short-term gain trumps long-term stewardship. And unlike 1875, we’re not waiting for distant experts to parachute in—we’re building the solutions right here on the North Coast.

The Kelp Festival isn’t just a celebration. It’s a chance to rewrite the story. To seed the sea with resilience. To choose restoration over extraction. To make Fort Bragg strong not just for a season, but for generations.

Let’s be the ancestors our future community will thank.

On the first weekend of October, Fort Bragg’s Kelp Fest dives into the deep end of science—offering innovative, and yes, even bizarre new ideas for keeping our giant bull kelp forests alive and thriving. From seaweed seed banks to shoreline plantings and selective breeding, researchers are reimagining restoration in ways that could make our coastal ecosystems more resilient than ever.

The stakes are higher now than they’ve ever been. In 1875, we gambled with forests. Today, it’s the ocean’s turn—and the consequences ripple far beyond the kelp. Whales, birds, fish, abalone, clams, and every living thread in the intertidal tapestry depend on us choosing restoration over ruin. The world is more imperiled, more interconnected, and more in need of bold, informed action than ever before.

This new science doesn’t ask humans to step back—it asks us to step up. Traditional environmentalism often preached that the best way to protect nature was to remove ourselves from the picture. But kelp restoration may be about rewriting that narrative. From breeding resilient strains to planting seaweed by hand and managing grazing pressures, the emerging science insists that human intervention—thoughtful, informed, and ongoing—is not the problem, but the solution.

It’s not about leaving nature alone. It’s about learning how to live with it, work with it, and restore it in ways our ancestors never imagined.

Scientists outline in their studies that the solutions probably won’t work unless the Mendocino County community and others around the state back them.

Science can show us the way, but only community can make it work. The researchers behind today’s kelp restoration efforts are clear: without local buy-in, the solutions may never take root. Mendocino County’s coastline isn’t just a lab—it’s a living system that depends on human stewardship. Whether it’s volunteers planting kelp, fishermen adjusting practices, or residents supporting policy shifts, the future of our bull kelp forests hinges on collective action. The science is promising. But without us, it’s just theory.

What’s Gone Wrong?

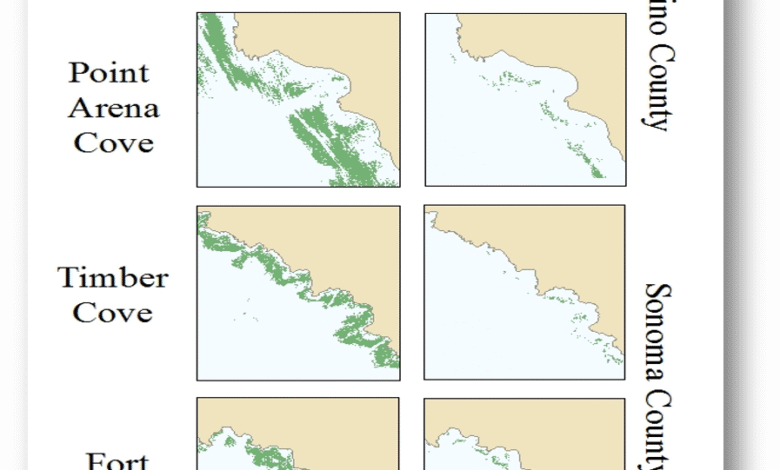

For the past 12 years, the waters off Sonoma—and especially Mendocino County—have been ground zero for a global kelp crisis. Once-thriving bull kelp forests have collapsed, triggering a cascade of ecological consequences that stretch from the seafloor to the open ocean.

This October, the North Coast Kelp Festival in Fort Bragg offers more than celebration—it offers solutions. The Nature Conservancy will unveil a bold new restoration program aimed at reviving kelp off Big River, using science that challenges traditional environmental thinking and calls for active human intervention.

The festival itself is a toweringly good idea for Fort Bragg. And the unveiling of Marta’s new full-sized gray whale mural couldn’t be more timely. It ties together two coastal giants—kelp and whales—whose fates are intertwined. With the kelp gone, the tiny crustaceans that once thrived in the muddy shallows have vanished. Gray whales, who used to dive close to shore and scoop up mouthfuls of mud to filter out these critters, are now forced far offshore in search of food. Their numbers are the lowest since the 1970s.

This isn’t just a kelp crisis—it’s a coastal reckoning. And Fort Bragg has a chance to lead the way forward.

Why We See Fewer Whales Off Fort Bragg

One reason we’re glimpsing fewer whales off Fort Bragg between 2023 and 2025 is simple: they’ve gone elsewhere. The collapse of our bull kelp forests stripped the nearshore mud bottom of the tiny crustaceans that gray whales once feasted on. Without that food, they’ve had no choice but to head far offshore.

The other reason is far more troubling. The gray whale population has crashed to its lowest level since the 1970s—back when the species was still clawing its way back from the brink of extinction after decades of hunting. It’s a sobering parallel, and one we’ll explore further in a subsequent article.

But there’s hope. The upcoming North Coast Kelp Festival is more than a celebration—it’s a chance to learn, to listen, and to act. It’s an invitation to understand the life cycle of the gigantic bull kelp that grows and dies off our coast each year, and to join the community in asking the hard question: why did we lose the entire forest a decade ago?

The reason is much more than what the scientific establishment and the media have told you. Yes, warming waters, urchin explosions, and climate change are part of the story—but they’re not the whole story. What’s often missing is the human context: how policy decisions, fishing practices, and decades of ecological neglect created a perfect storm. How local knowledge was sidelined. How restoration efforts were delayed while bureaucracies debated.

The kelp didn’t just vanish—it was abandoned.

And now, the North Coast Kelp Festival offers a chance to reclaim that narrative. To ask deeper questions. To listen to scientists, yes—but also to divers, fishermen, tribal leaders, and longtime locals who’ve watched the ocean change in real time. The truth is layered, and Fort Bragg is ready to peel it back.

Rewriting the Kelp Collapse Narrative

In 2012, Noyo Harbor urchin diver and businessman Tom Trumper stood before the Marine Life Protection Act Initiative with a warning: if fishermen and human stewardship were excluded from managing urchin barrens, the kelp and abalone would be doomed. He wasn’t speculating—he was witnessing the decline firsthand. But the environmental establishment didn’t listen.

This was before the die-off of SunStars. Before the media latched onto the purple urchin invasion as the singular villain. In truth, the bull kelp forests had been in steady decline since the 1990s. Off Caspar, urchin barrens had already taken hold well before starfish wasting disease emerged in 2013.

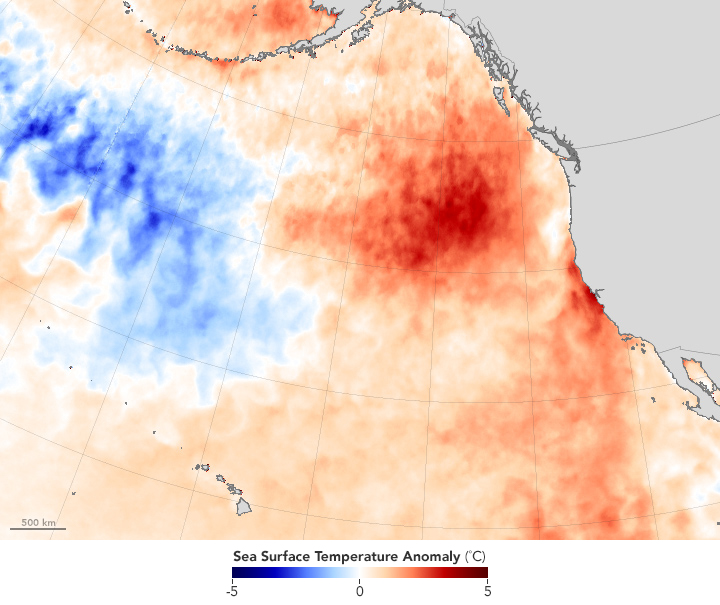

The real tipping point came in 2014, when a massive warm-water anomaly known as “the blob” surged up the Coast. It was unprecedented, unpredicted, and devastating. The blob disrupted nutrient flows, weakened kelp resilience, and accelerated ecological collapse. At the time, it was seen as a freak event. But it has since returned—twice—and is now said to be back again.

The kelp wasn’t killed by a single cause. It was a slow-motion unraveling, worsened by policy missteps, ecological blind spots, and a refusal to heed local knowledge. The North Coast Kelp Festival offers a chance to set the record straight—and to chart a better course forward.

Pacific ‘blob’ heat wave now spans an area the size of the US

The Myth of the Missing Sun Stars

Yes, starfish wasting disease took hold in 2014, likely worsened by the arrival of the warm-water “blob.” And yes, the purple urchin barrens expanded rapidly, devouring what little bull kelp remained. But let’s be clear: the absence of Sun Stars, while unfortunate, was never going to save or sink the kelp forests on its own.

The idea that Sun Stars once kept urchin populations in check is more myth than mechanism. These predators were part of the ecosystem, but never in numbers or behavior capable of controlling the kind of urchin explosion we’ve seen. The real culprits are warmer waters, weakened kelp, and a lack of human intervention when it was most needed.

The kelp didn’t die because the Sunflower Sea Stars disappeared. It died because the system was already unraveling—and we failed to act or even realize the catastrophe that was underway. The nutrient-poor waters associated with marine heatwaves hinder kelp growth, leading to smaller canopies. Historically kelp have been resilient, though, coming back in force once waters have cooled down. But this time, a cascading series of environmental and biological events—exacerbated by climate change—combined to decimate the forests.

What caused the warm seawater blob? That’s still unclear. Climate change has warmed oceans globally, but it wasn’t the direct cause. Shifting currents—likely influenced by climate change—played a major role in stirring up the anomaly.

Kelp declines aren’t limited to Mendocino. Giant kelp off Monterey also crashed during the same period. But there, neither the blob nor starfish die-off were factors. The truth is, kelp forests are collapsing in different places for different reasons—and we’re only beginning to understand the full picture.

Off the Mendocino Coast, more than 90 percent of the kelp forest vanished after 2014. While many areas have seen signs of recovery since then, the kelp beds off Big River tell a different story. Much of the kelp there survived the initial die-off—only to mysteriously collapse around 2021.

And the usual suspects don’t apply. Urchin barrens aren’t a major factor there. The Sun Stars were already long gone. The dreaded ocean blob wasn’t active at the time.

Something else is happening off Big River. And it’s time we asked harder questions.

“Following the uncharacteristically warm seawater conditions in 2014–2016, regional kelp biomass was generally characterized by patchy declines in the south, declines in central California, and extreme declines in northern California,” one scientific report notes. Tribal citizens have echoed this, pointing to steep declines in their traditional harvesting areas along the North Coast.

These weren’t isolated dips—the one here was an ecological freefall. And while the blob was the headline, the deeper story is layered: warming currents, weakened kelp, sidelined local knowledge, and a system already teetering before the heat arrived.

The Calfornia Department of Fish and Wildlife’s kelp status reportsays this.

So what happened?

A slow-motion collapse. Warming currents, shifting ecosystems, and policy missteps weakened the kelp long before the blob hit in 2014. The die-off wasn’t sudden—it was ignored until it was too late.

Can humanity help bring it back? Yes—but only if we act differently this time. Restoration science now calls for hands-on solutions: planting kelp, managing urchins, breeding resilient strains. It’s not about stepping away—it’s about stepping in. With community support, we can rebuild a stronger, more resilient forest. But it won’t happen without us.

For this to happen, you—the reader—have to care. Not just skim headlines or scroll past the crisis. You have to follow the full story, ask hard questions, and yes, turn off the cell phone. You have to show up.

Start by joining the 9 a.m. tour of Big River Beach on Oct. 5. See the coastline. Hear the science. Feel the stakes. Because restoring the kelp isn’t just about ecology—it’s about community. And it begins with you.

Perhaps most fascinating of all is how the scientific consensus has evolved. Today’s restoration strategies echo what Tom Trumper warned over a decade ago: that excluding humans from the equation would doom the kelp and the species that depend on it. The new science doesn’t call for ocean parks sealed off from people—it calls for collaboration, stewardship, and smart intervention.

It’s a vision perfectly aligned with the principles of the “Blue Economy,” where enterprise, ecology, and community well-being are served together—not separately. It’s not just about saving kelp. It’s about building a future where Fort Bragg thrives by working with the ocean, not just watching it.

These are radical ideas for anyone who studied the environmental sciences over the past 30 years.

Every serious solution to the kelp crisis involves human intervention—anathema to the old-school environmentalism that shaped the MLPAI and its marine exclusion zones. For years, the prevailing wisdom was to fence off nature and let it heal itself. But kelp doesn’t work that way. It’s fast-growing, fast-dying, and deeply sensitive to changing conditions. Without active management—planting, thinning, breeding, and even harvesting—there’s no path to recovery.

The irony? The science now backs what local voices like Tom Trumper said all along: humans aren’t the problem. We’re the missing piece.

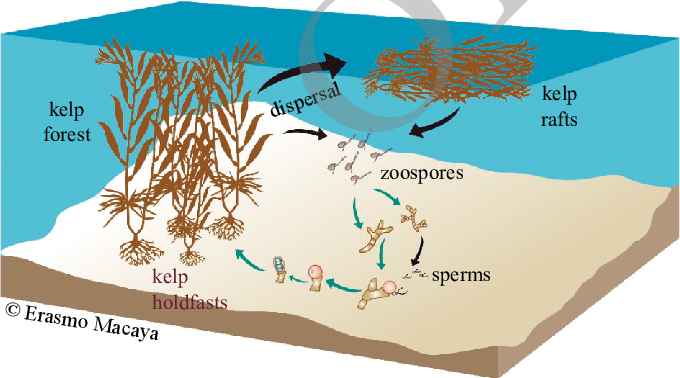

The future of kelp may depend on human hands. One promising strategy involves raising kelp in tanks to acclimate them to the warmer waters that helped trigger the collapse. Another calls for selective breeding—identifying and cultivating kelp varieties that thrive in rising temperatures. And already underway is a global effort to gather local kelp spores for inclusion in a massive worldwide seed bank, ensuring genetic diversity and resilience for generations to come.

These aren’t passive solutions. They’re bold, hands-on interventions—and they mark a turning point in how we think about ocean restoration.

Scientists at UC Irvine adapted a Norwegian kelp-outplanting method for California: growing giant kelp seedlings on gravel in labs, then scattering them on the ocean floor to test restoration potential. They also found that exposing young algae to warmer water can harden some kelp populations against heat stress—offering a path to “future-proof” restoration by selecting strains more resilient to climate-driven ocean warming.

Read more here.

A consortium of researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, UC Santa Cruz, and USC has built a seed bank containing more than 1,700 bull kelp genotypes from 14 sites along Northern California’s coast. A duplicate archive now resides at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach. These collections aim to safeguard the genetic diversity of imperiled bull kelp—preserving options for restoration and resilience for decades to come. And possibly to select hardier varieties to match climate change.

Read more here.

Could Sea Otters Help Mendocino’s Kelp?

One idea gaining traction is reintroducing sea otters to the Mendocino Coast. Historically, otters helped control sea urchin populations, playing a vital role in kelp forest health. But European and Russian hunters wiped out otters from Alaska to Southern California in the 19th century. Only one population survived—hidden in Monterey—where they still thrive today.

Yet science urges caution. Reintroducing a species into an altered ecosystem can backfire. Otter reintroductions are a checkered story. Tribal and environmental groups have worked together to put an effort in motion to bring back otters in Oregon and far Northern California, leaving the area from north of Santa Cruz/Monterey to the Humboldt County line as the main place otters are not. Some tribes have resisted reintroduction in Alaska and Canada, seeing what happened to their food resources when otters were brought back in other nearby areas. Here is what is happening north of Humboldt County and in Oregon:

Siletz Tribe gets $1.56 million to reintroduce sea otters to coastal waters – OPB .

In California, efforts to help them spread north have largely failed. Great white sharks, now more abundant due to booming seal populations, have killed most otters venturing north. And the waters north of Monterey rugged coastline lacks the offshore islands that offer otters safe refuge so they remain stuck there.

It’s a compelling idea—but one fraught with ecological and logistical challenges. Local fishermen fear otters would doom the abalone forever.

One of the biggest declines in giant kelp since 2014 happened off Monterey—ironically, the very place where sea otters are most abundant. That collapse underscores a critical point: while otters help control urchins, they can’t shield kelp from broader forces like warming waters, shifting currents, and ecosystem stress.

Otters may or may not be part of the solution—but not the whole story. Restoration will require a mix of science, stewardship, and community action. And it starts with understanding what really went wrong.

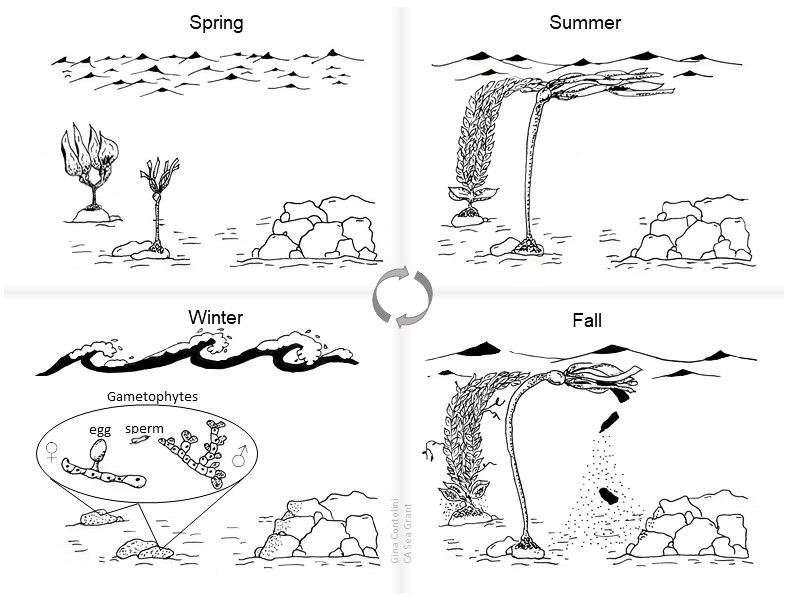

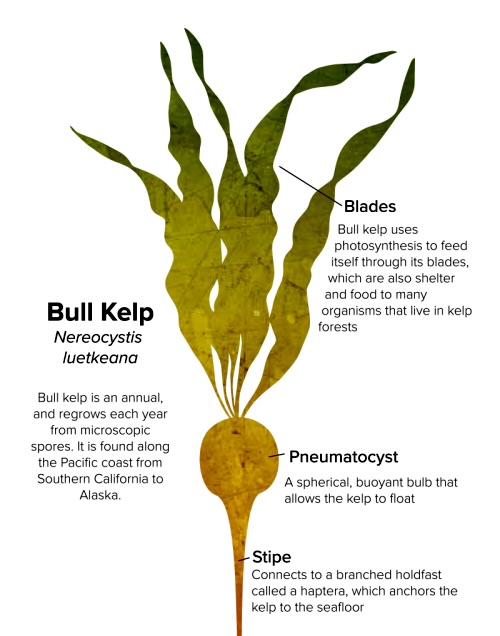

Bull kelp forests are as vital to the Mendocino Coast as redwoods. They’re one of the fastest-growing organisms on Earth—shooting up to a foot a day—but they live only a single year. Their life cycle is brief, but their impact is immense.

For thousands of years, Indigenous people followed the “kelp highway,” a ribbon of life stretching down the Pacific, offering food, shelter, and safe passage through waters often barren compared to the Atlantic. When settlers arrived, they wiped out sea otters from Alaska to Monterey and displaced the Indigenous stewards of the coast. With the otters gone, abalone populations exploded, and the newcomers took everything—rockfish, shellfish, and eventually the abalone itself.

Kelp forests create something extraordinary: a living, breathing aquarium on a massive scale. Towering fronds feed and protect countless species, anchoring an ecosystem that once thrived—and could again.

Walk the beach and witness the cycle. Each fall, storms tear up the bull kelp that grew skyward all summer—up to a foot a day. Washed ashore, it feeds crabs, fish, flies, maggots, and the birds that feast on them. From fresh fronds to decaying ribbons, kelp fuels the entire coastal food web.

It’s the ocean’s solar engine—feeding on sunlight, buffering waves, and sequestering carbon on a massive scale. Anchored by a strong foot clinging to rock, kelp rises toward the surface, where its air-filled bulb floats and photosynthesizes like a plant.

But kelp isn’t a plant. It’s brown algae—from the third kingdom of life. And it’s the quiet giant that makes this coastline thrive.

Two giants rule the underwater forests of California: bull kelp and giant kelp. Bull kelp, dominant north of San Francisco, stretches 60 to 100 feet from seafloor to surface—sometimes reaching 135 feet. South of San Francisco, giant kelp takes over, growing up to 200 feet tall in dense, cathedral-like groves.

But warming waters are driving all sea life northward—shorebirds, seabirds, fish, and invertebrates—all fleeing heat. Climate change is already reshaping species ranges and threatening extinctions. And yet, at the heart of coastal life remain these two kelp species, anchoring ecosystems, feeding food webs, buffering waves, and sequestering carbon.

Bull and giant kelp are not just algae—they’re the scaffolding of ocean life. And if saving them means playing God, then so be it. That’s the stance of Sea Grant-led restoration efforts: intervene, innovate, and act before the forests vanish for good.

Humans created the noxious purple urchin barrens—by overfishing red urchins, with pollution, with the warm water. Without their natural competitors, purple urchins exploded in number, overrunning the seafloor like army ants devouring a jungle.

And here’s the kicker: even when they’re half-dead, purple urchins don’t let go. They can linger on a single rock for decades, slowly wasting away in a zombie-like state. No kelp can regrow there. No crab or fish gets that space back. It’s ecological gridlock—engineered by us.

Turning a Menace into a Meal

At the Noyo Center for Marine Science, researchers are experimenting with a bold idea: taking starving purple urchins from the barrens, fattening them up onshore, and turning them into a viable seafood product. It’s a win-win—restoring balance to the ecosystem while creating economic opportunity.

If the Blue Economy can establish a market for purple urchin roe, these pests could become a commercial asset. Harvesting them before they overrun the seafloor again would not only protect kelp forests—it could fuel jobs, innovation, and sustainable seafood right here on the Mendocino Coast.

It’s restoration with a fork and a future

Before the Collapse Had a Name

In 2012, urchin diver and businessman Tom Trumper invited anyone willing to see the devastation firsthand. Among those who took him up on it was the late Bill Lemos—one of the Coast’s most respected environmentalists and a key supporter of the MLPAI process. What Lemos saw underwater astonished him. It didn’t erase his support for marine protections, but it did shift his perspective. The barrens were real. And they were growing.

Even earlier, in 2011, journalist Frank Hartzell quoted Trumper warning of doom for abalone and kelp—forecasting the rise of urchin barrens before the starfish die-off that’s often blamed for it all. Trumper saw what others missed: that human choices, not just ecological accidents, were driving the collapse.

Here is that Advocate News article by Frank

We’ve been watching this coast longer than many of today’s experts have been adults. And while we respect the scientists—we’re not them—we also know that science often catches up to what fishermen, divers, and tidepool wanderers have been saying all along.

The delicate interplay of species that safeguards kelp forest biodiversity did suffer a shift in 2013 when more than 20 sea star species from Alaska to Mexico, especially the sunflower sea star started wasting away due to the then mysterious sea star wasting disease. In 2025 a bacteria resembling cholera. was identified as the cause

As a diver in the 1990s, I loved the Sun Stars. Big, beautiful, and rare compared to the common ochre stars. I saw them often, and every time I did, I thought: leave them be. They’re too few, too majestic, and never in numbers that could control sea urchins.

The idea that Sun Stars were the missing link in kelp collapse? That’s not what we saw. The truth of system wide decline was already on the rocks, in the tidepools, and beneath the waves—if you knew where to look.

The Bull Kelp Are Coming Back—and So Are We

One reason for the rebound? A corps of heroic divers, assembled to kill purple urchins by hand. These aren’t fishermen in the traditional sense—no one wants the catch. The goal is removal, pure and simple. And the effort has earned the blessing of environmentalists who once pushed to make vast stretches of ocean off-limits to humans. The tide has turned. Marine protected areas have their place, but managed fishing and active stewardship are proving more effective.

And now, the most exciting moment of the Kelp Festival is here—a symbolic and literal turning point in the fight for resilience. The kelp are rising. The community is rallying. And for the first time in years, hope is floating on the tide.

We need events like the Kelp Festival to open doors: between the public, investors, and the researchers chasing answers for all of us. Because the ocean doesn’t wait for consensus. It responds to action, to curiosity, to care.

And if we want kelp forests to thrive again—not just survive—we’ll need all three.

The kelp forest at Big River held out longer than most—surviving the catastrophic die-offs of 2014–2019 that wiped out over 90% of bull kelp along the North Coast. But in 2022, even this resilient patch began to unravel.

The cause? A complex mix of lingering stressors. While the Sun Stars were long gone, their absence still echoed in the ecosystem. Purple urchins, even half dead, continued to pressure kelp. Warmer water events—though not as dramatic as the 2014 “blob”—persisted, weakening kelp growth and reproduction. And the cumulative toll of climate change, shifting currents, and ecological imbalance finally reached this last stronghold.

By 2023, 91% of the kelp refugia at Big River had vanished. It wasn’t one big event—it was death by a thousand cuts. And it sparked a call to action.

The Nature Conservancy, alongside local divers, scientists, and community partners, launched a restoration effort to reforest the 15-acre site. Their work includes experimental outplanting, urchin removal, and community engagement—all aimed at protecting what’s left and rebuilding what was lost.

Sources: Big River Kelp Recovery Project

Reef Check Restoration Summary

Come out Oct. 5 at 9 a.m. and learn about the strategies the Big River Kelp Recovery team has developed to suppress purple urchin populations and outplant baby bull kelp. Be among the first to receive the report on this year’s kelp recovery. Watch a kelp-mapping drone demonstration and discover how this technology helps monitor progress year over year. Team members will also share methods of urchin harvesting, kelp outplanting, and creating a visual record of seaweeds across this vital recovery site.

Here is what you need to know about this can’t miss event

For this event, meet on the bluffs above Portuguese Beach at the west end of Mendocino just off Main Street. Small groups may be led down to the beach to observe kelp wrack and live urchin harvests.

One big reason people fall for conspiracies—or even flat earth nonsense—is that science communication is often abysmal. Scientists can be brilliant, but they’re notoriously bad at explaining things to regular people, and even worse at listening to ideas outside the consensus. That disconnect breeds distrust. People who’ve spent their lives in the field or on the water start doubting everything—and voting accordingly.

We need a massive investment in science education and communication. And we need journalism again. Local science reporting used to challenge official narratives, many of which later proved wrong or incomplete. And people working in science must realize they cannot speak for some financial interest or grant and have a clear conscience. Truth is essential for all of us to survive.

Frank often tells the story of “discovering” a mountain lion on his grandparents’ farm in Illinois. His grandmother helped him gather evidence—a deer kill, lion tracks, photos—and take it to the university. They were laughed out of the room by young grads who’d never set foot in the hollers, draws, or cricks. Decades later, authorities admitted what locals had always known: big cats were rare, but they were there.

That moment cracked something open. Science wasn’t wrong—it was blind. And as the years passed, more examples piled up. What’s even more astonishing is how many people never question the official story at all. They don’t look. They just believe.

For the past ten years, Frank Hartzell has quietly visited a remote spot in Caspar—one untouched by divers—to remove purple urchins. I won’t say where; the last time I did, the place was damaged by careless visitors.

Around 2018, the urchins took over. But in 2021, I saw something astonishing: the largest ochre stars I’ve ever encountered, wrapped around urchins. When I returned in 2022, the urchins were nearly gone. Mussels had returned. Seaweeds too. I didn’t go deep enough to check for bull kelp, but the transformation was real. I have seen ochre stars eat urchins—something science says is impossible. But it happened, right there in the tidepools.

That place changes every year without human intervention. The tidepools and near shore waters are beautiful but also involved in a deathly competition for survival I saw ochre stars eat urchins—something science says is impossible. But it happened, right there in the tidepools. Like the lion in Illinois.

We even filmed an octopus there once. I only brought my camera once—those rocks are slippery—and missed capturing the dinner-plate-sized ochre stars. They were gone the last time I visited.

Let’s believe in science, but also help it.

Question it. Ground it in lived experience. And most of all, turn off the phones and get outside. The answers are waiting—if we’re willing to look.

For now, we need to kick the Sun Star narrative to the curb. It’s not the whole story—and chasing it won’t save our kelp.

What will? Listening to divers, scientists, tribal voices, and coastal communities. Investing in restoration. Acting boldly.

The kelp won’t wait. Neither should we.

So come care with us. Walk the beach. Ask questions. Listen deeply. Be part of the story. The ocean is calling—and this time, it needs all of us.