Clear the Path to the Waves: We Urge Removal of the Neighborhood Group’s ‘Stop’ Sign, Restore Pine Beach Access, and Celebrate the Classy but locally friendly New Inn’s Arrival

MendocinoCoast.news believes it is our responsibility to champion public access to public lands too long kept out of reach. Today, we take up that charge with the beach that first opened below the Pine Beach Inn in 1938—now reborn as The Mendocino Cove—and with a second nearby area still restricted. Our work is to clear the path, restore the public’s right in all cases. We congratulate the owners of The Cove and their project and believe they will help find the best solution to access that has been blocked for several years and for return of the parking at the trail head to Pine Beach. We believe this could be the BEST ADA access on the entire Coast!!

We are not righting a historic wrong here, but more what appears as a ommission and blocking access for years due the pandemic chaos. These areas of public land have long carried unclear access rights—shaped by shifting traditions, changing times, and ownership patterns that never placed public access as a priority. Today, we choose to give it a try.

We think it’s an excellent time to provide parking and public access to the beach below The Mendocino Cove. We are also asking that a STOP sign on nearby Ocean Drive be removed, although this sign appears to have never been related to either the Pine Beach Inn or The Cove. And its also apparently a relic of bygone people and times.

Surprisingly, removing the sign could solve both problems—if our proposed solution proves legally possible. We urge removal of the sign and the opening of the newly constructed parking lot just beyond it. From there, people could park and access both areas of public land without intruding on nearby residents or the fine new inn.

Unlike in some other places we have worked, we have not been met with resistance here. In fact, our conversation with Chris Hougie, owner of Mendocino Cove, confirmed that rumors of blocked public access were false. At a recent open house, some referred to it as the “private beach,” but Hougie acknowledged that people have the right to walk to the shore and made clear he will not continue to block access. While the seven‑foot chain‑link fence did restrict entry for the past five years, we understand that was due to the pandemic and ongoing construction.

In fact, contrary to the rumors, Hougie was willing to discuss the issue and appears open to finding a solution to the long‑unasked question of public access. He has stated he will not block anyone from walking to the beach through The Mendocino Cove property and does not know who placed the “STOP” sign, which has stood for many years.

Over 87 years of existence, access to the beach at Mitchell Creek has rarely been a major issue. In the 20th century, people simply walked to all beaches without concern. Later, two different owners charged for parking, but few objected at the time. Each owner treated access differently. When my parents arrived in 1985, they could walk down by parking behind the Inn. Subsequent owners charged either for beach access or for parking.

Meanwhile, laws shifted. The California Coastal Commission, established in 1972, required that no construction block public access to beaches. Yet each case is unique where private property predating those laws must be crossed. The debate has played out at nearly every beach in Southern California.

Now, with the largest renovation in decades and a grand new property opening, the moment feels right to resolve this question. At the next beach to the north, the Mendocino Land Trust helped map out a trail across private property—one that even weaves through the yards of million‑dollar homes—to ensure access to another small beach.

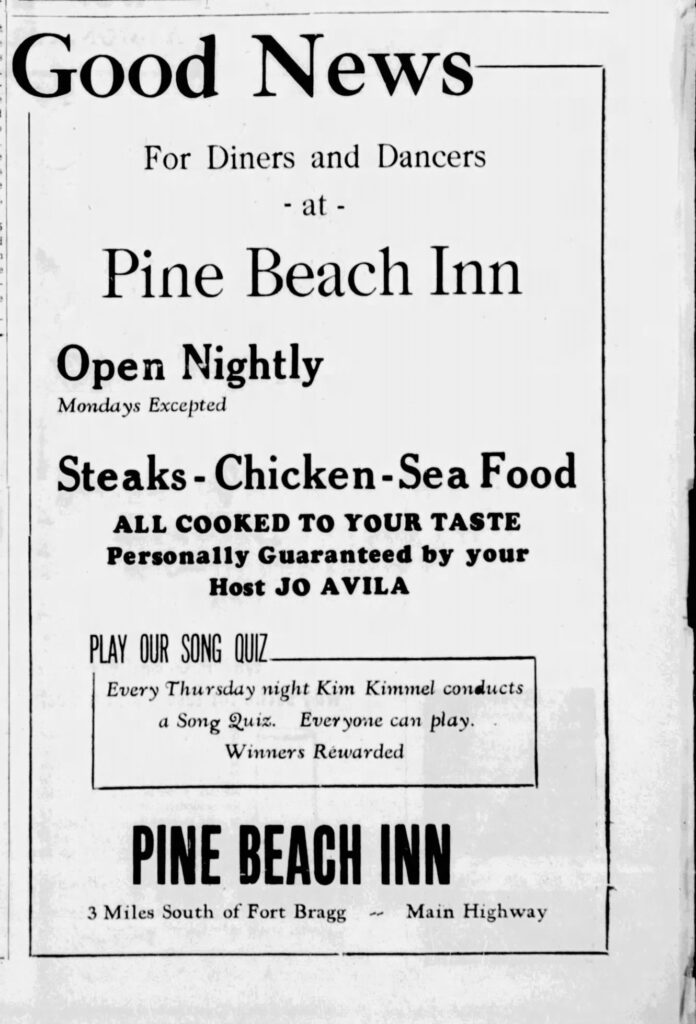

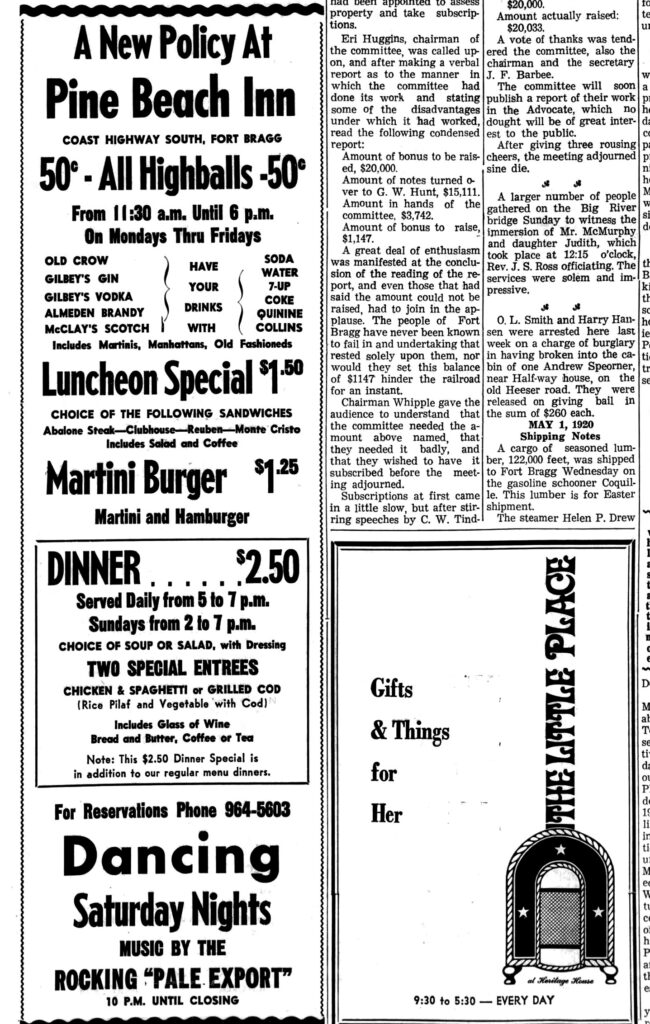

The Pine Beach Inn began as the Mitchell Creek (motel) before changing its name to Pine Beach—at a time when inns were often identified simply by their location. When Pine Beach opened in 1938, it featured eight auto cabins, a popular draw for travelers of the day, along with a main building that housed a dance hall, bar, and restaurant. The name reportedly came from the handsome yellow pine used in its construction.

Pine Beach, and later Pine Beach Inn, was frequently in the headlines of local newspapers for its events, bowling league victories, and community involvement. During an era when Fort Bragg was crowded with taverns and barroom brawls, the Pine Beach Inn catered to an older crowd with ballroom and square dancing. Old ads and news articles highlight evenings with a pianist or organist, pointedly avoiding the “ doo-wop of the 50s and crazy new Rock and Roll of the 60s.” The brawlers left Fort Bragg, passed the martini and big band fun at Pine Beach and showed up for more wild times at Caspar Inn.

Some owners leaned into tradition, offering fine Italian dinners and crab cioppino in the Franciscan Room, proudly noting the inn was “just four miles south of Fort Bragg.” Others tried to distance themselves from Fort Bragg altogether. In the mid‑1970s, one owner advertised the inn as a “boutique” five miles north of Mendocino, while another more truthfully placed it seven miles north. The Mendocino Grove seems to be trying more of the second approach.

Their music was always part of the Pine Beach charm and don’t knock it for being square. One of the regular performers was a young Bob Ayers, the late musician beloved by hippies, country folk, and the local music scene for four decades with his Boonville Big Band. Even after the passing of their colorful leader, the Bob Ayers Band continues to play, carrying forward his legacy.

Each new owner received fairly in‑depth coverage in the local papers—often with different versions in each—detailing their plans, community involvement, and especially the bar, menu, and music. Yet nowhere did we find any mention of the beach. In the 20th century, it would have been unheard of to charge for such a thing, but the subject simply never came up in the records we found. As current owner Hougie told me, the truth is that it’s a small beach, one that has never drawn much attention, and so its status has drifted quietly along.

We plan to work toward establishing public access to all beaches along the Mendocino Coast as time goes on. We ask for patience with this process, as solutions require careful attention to legalities and to where and how access should be provided. Yet after years of examining this issue, we believe the time has come to finally get an answer here and in a few more spots.

There are two issues at play here. One is not directly tied to the Pine Beach Inn of the past or to The Cove that stands there now. Yet both, in our view, can be resolved with a single action.

Problem #1: The Sign

We urge whoever posted the homemade sign at the western end of Ocean Drive to remove it. The sign orders anyone not living at a listed set of addresses to turn around and leave. Yet the primary property owner behind that “STOP” sign is California State Parks. The sign now blocks access to marked State Parks trails and even a newly designated parking area—an area that could also solve Problem #2.

Problem #2: Access to the Beach

When Chris Hougie and Teresa Raffo bought the Pine Beach Inn in 2020—just as the pandemic hit—the property had long before fallen from the glory days of the Franciscan ballroom into disrepair and was no longer a vital part of either the Fort Bragg or Mendocino community. The pandemic slowed everything. Soon after, a chain‑link fence went up, completely blocking access to the parking area at the western edge of the property that many of us had used in years past. At the time, it wasn’t the moment to raise the issue.

We were surprised, however, that the fence remained for five years and even went back up after the November 23 open house. Construction does continue, and the new owners are building something impressive for the town—perhaps as lively as the old Franciscan Room (whether named for the local geology or the religious order). But now, the time has come for beach access to be restored, both for parking and walking. The owners have already built a paved, beautiful trail down to the shore—potentially one of the coast’s most ADA‑friendly beach accesses, alongside the rougher, tougher, larger Noyo River Beach. But walking down from Highway 1 doesn’t seem to fit that bill, at least to us. We met and talked to a few neighbors at the time, but after talking to Hougie and having him and our research making us realize that this situation was really not any sort of a scandal something that simply had been overlooked, we decided not to stir up any more of a fuss, and simply perform our role as journalists— always pushing for public access to public records and lands.

The new owners have also built a well‑designed parking lot along Ocean Drive, complete with a road gate and a wooden gate that can be opened and closed for cars to enter and exit. They even installed a dog‑waste bag dispenser. When I asked Chris Hougie about this, he requested more information. He appears to be considering the best way to provide beach access and has suggested parking along Ocean Drive as one possible option. There may be legalities or laws that prevent our proposed solution of the parking area, but we wanted to suggest that and see where it goes.

So, remove the “STOP” sign—regardless, in our view—and then, if legally possible, open public access to the parking area. At the same time, alert nearby residents to stop chasing people away from the State Parks trails or from walking all the way to the end of Ocean Drive. Visitors who stay to the left remain on State Parks land and can continue out to the bluffs.

At MendocinoCoast.news, we continue to uphold causes that journalists once universally embraced. We fight for public access to records and meetings, and as California journalists, we believe all beaches should be open to the public—especially those historically accessible. We do not believe it is legal to charge for parking to reach the beach, and parking should be available as close to the shore as possible.

Last year, we raised concerns when the owners of Albion Campground charged for parking. They have since stopped, after others joined in the effort. We already have at least two more sites where we plan to campaign for restored public access once this case is resolved.

These cases are never simple. Most predate the California Coastal Commission and nearly always require negotiation between reasonable parties—as we seem to have here, between the owners and the state. We know both sides, and we believe this issue can be solved, with public access restored.

Meanwhile, one of the coast’s most striking hotel transformations is nearing completion. Mendocino Cove, a nine‑acre retreat, will feature a sauna, hot tubs, public pickleball courts, and a full restaurant and bar. Considering where the property began, this stands as one of the most impressive hotel renovations in years.

We toured Mendocino Cove and came away deeply impressed. Even unfinished, it already shines as a coastal gem—one that may soon offer rooms where locals can host visiting friends and family. While it won’t be bargain‑priced, it also avoids the air of exclusivity reserved only for the ultra‑wealthy.

During the November open house, we followed the newly blacktopped trail to the ocean—a welcome upgrade from the bumpy, rutted path it had been before the new owners took over. That trail had been blocked for five years during renovation. We never believed such a closure was legal under California’s Coastal Act, yet the entire area was fenced off throughout the lengthy construction. Hougie explained the closure was necessary because construction was active and the property unsafe to traverse. I don’t doubt this; the work was on and off, and their lovely property would indeed have been left unprotected at times.

Now, with the project nearly complete, the result promises to bring both pizzazz and economic vitality to the Coast. During construction, nobody—including us—complained about the lack of public access. But we believe the time has come to establish a clear, visible solution. While it may not be reasonable to demand access before construction is finished, we want to set the process in motion now so that beach access opens as the new hotel opens.

Although the names are public records we excluded them as unneeded for this story. MC & BC is the legal name of Mendocino Cove.

We have asked the Coastal Commission to review this matter and determine how access to the public beach should be provided. In our view, the solution lies in the parking area built along Ocean Drive—situated on the property but not interfering with The Cove in any way. From there, visitors could simply walk down the new paved trail to the shore.

If that happens, the brand‑new parking lot instantly becomes public‑friendly. Folks can park, take the trail, and never have to bother—or even glimpse—anyone at Mendocino Cove. And the inn still retains bragging rights as the only hotel with its own beach… one it shares with the public, just as California’s Coastal Act intended all along.

Below, you can see the parking lot established along the road, opening the way for visitors to enjoy both the beach and 17 acres of California State Parks land—separate from The Cove. Trails branch off along the route, offering access to the wider coastal landscape.

While a pedestrian gate leads onto the so‑called “private” road, the parking area itself—spacious enough for seven or eight cars—is perfectly suited to allow public access to the beach. Visitors could use it without being required to become paying customers of The Cove or its not‑yet‑opened restaurant. Of course, the legalities remain uncertain. It looks promising, but Hougie and the Coastal Commission will have to take it from here. The Commission may be feared by those dodging permits, yet in settings like this they are often reasonable—especially when working with someone like Hougie, who isn’t thumbing his nose at them (that’s been tried before, and we don’t recommend it).

But there are two questions here: driving and parking. Hougie said The Cove would not block walking access to the trail or prevent anyone from crossing the inn’s property to reach the beach. Like others we spoke with, he was unsure about the STOP sign and thought it might be a good idea to remove it. He explained that the subdivision project beyond the sign was developed before laws changed, and said he would welcome a solution to our concerns. As we noted, this issue does not appear to have surfaced publicly in the past.

Hougie noted that there is a public parking lot at the corner of Ocean Drive and State Route 1. We don’t believe that’s close enough to qualify as true beach access. He also mentioned other areas along Ocean Drive.

From that lot at Ocean Drive and Highway 1, visitors can actually walk all the way through the State Park and emerge at the other end of Ocean Drive. Hougie believes people should be able to park there, walk through the State Parks land, and continue down to the beach. But other neighbors don’t see it that way.

Frank has been harassed three times for using the western end of Ocean Drive. Only once did I ever drive past the sign. The other two times I was walking—and still drew ire from residents—even though I never stepped onto their property, only Ocean Drive and the State Parks trails.

We’ve been confronted three times on this road. The first time was purely accidental—Frank entered at the corner of State Route 1 and followed a well‑marked, popular State Parks parking lot. Nobody disputes that this lot is public. From there, he stayed on the signed trails and ended up on a bluff alive with pelicans, where a few men were fishing and proudly landed a magnificent lingcod.

We followed a trail out and eventually found ourselves on a road. Frank wasn’t sure where he was. As he began walking back down, a man suddenly called out, loud and sharp: “You are trespassing.”

It was a shock. I wasn’t sure if we were trespassing or not. I answered meekly, “Sorry, I thought I walked on a State Parks trail to get here.” His reply was blunt: “You had to leave the park and trespass to get here.” I asked if we could talk, but he went silent—like some disembodied “voice of God” in a Hollywood movie. Informational, not threatening, but absolute.

For a moment, I wondered if he was right. But I was certain I’d seen a sign. So I retraced my steps, and sure enough—at the end of the road stood a State Parks marker directing walkers to a public trail. The so‑called “voice of God” had misled me.

I called back, “Hey, I took a picture of the State Parks sign—want to see it?” Silence. By then I was fuming, at both the phantom voice and myself. Even if driving on that road were questionable, walking was not. He knew that, yet chose to harass me. Pleasant tone or not, he was wrong.

I walked the mile back down Ocean Drive—having never driven past the “STOP” sign—to the Honda, vowing to find out whether it was truly illegal to walk or drive beyond those homemade signs.

That was in 2023. Since then, I’ve walked from the indisputably public lot down that road several times without incident. On one occasion, a man working on a truck just past the gate waved—and even greeted me by name.

Harassment number two was milder. I had posted photos of pelicans, yard art, and houses from the bluffs. A friend messaged me: “That’s private property.” I asked her to explain—I’d entered from the public lot. She told me to lighten up; she knew how I’d come in. (Do these people have eyes and voices in the sky?) When I pressed further, she admitted the property owners probably wouldn’t mind me being there, but asked me to stop posting photos that might attract “all kinds of people.” Apparently, Mendocino can’t have folks out looking at yard art.

When I went to Ukiah the following week, I dug into the question. The maps made it clear: State Parks owns more land along that road than anyone else. So how could they possibly close it off? (See maps.)

That was in 2024. Then came the case of a woman yelling at me in July 2025. I drove down the road, parked in the State Parks–marked lot, and took the dogs for a walk—down the road to the end, along the signed trail, out to the bluffs, and back again.

When I returned to the car, a woman stormed down her driveway, shouting that I was trespassing and that she would call the police. I wish I had let it end there. Instead, I fired back with my own legal threats, vowing to prove in court that this road should not be restricted. It is an important issue—one I regret handling in that way.

Partly feeling foolish about how that last encounter went, I did nothing—until this month. That’s when I noticed her so‑called “private” road had opened a gate leading to the beach behind The Cove. A parking lot had been built, and a trail established. It felt like the perfect moment to reclaim public access to the beach at the end of Mitchell Creek—and to the state properties beyond the STOP sign we believe is illegal. Mendocino Cove wouldn’t even be inconvenienced.

Hougie also raised a strong point that deserves attention: the entire State Parks forest is a serious fire hazard. Neighbors have asked State Parks to address it and even offered to do the work themselves, with permission, but have received no response. In walking the Coast, we’ve seen many areas, and this is among the worst for downed trees, heavy brush, and dry grass. This situation should be resolved alongside clarifying public access.

From what we’ve heard from Hoagie, the Cove is intended to be a welcoming place for everyone. The inn will be divided into two parts: the front, a low‑to‑medium seasonal motor lodge where locals might host out‑of‑town guests in fresh, comfortable digs; and the more upscale rear buildings, some with ocean views. Hoagie has not yet decided on the restaurant’s opening date or menu, but assured us that considerable thought has gone into the effort.

An Indian restaurant, I begged.

He said it will be more American food very good and reasonably priced.

We have asked Bill Maslach, superintendent for State Parks in Mendocino and Sonoma counties, about access to State Parks lands and how the fire hazard next to people’s homes might be addressed. We will report on that story once we hear back.

By bringing this story forward, we hope both the homeowners and The Cove will respond with a clear plan to restore public use of the parking lot—currently accessible only via the so‑called “private” road. If the parking area already created on Ocean Drive were opened to the public, the paved trail to the beach that The Cove built would be ADA‑accessible, or at least usable for disabled visitors to reach the water’s edge. However, this lot has not historically been used, and the Coastal Commission would need to work with Hoagie on the matter. If that solution is not pursued, we believe the parking area at the western terminus of the Pine Beach Inn/The Cove lot should be restored.

to Pine Beach and a chance to see Mitchell Creek flowing into the ocean.

We believe the fees charged by the previous owners during the Pine Beach Inn days were illegal. Even then, we would park, dine at the restaurant, and walk down to the beach. Although a sign insisted that only hotel guests could use the access, we were never stopped—as paying customers of La Playa, and later the Thai restaurant that replaced it—from enjoying the shoreline.

Mendocinocoast.news is demanding access to both the road and the beach. Hopefully that was the plan all along, but it’s time to put it on the record. Granting public access would resolve the issue entirely: visitors could reach the bluffs and shoreline without ever needing to park on The Cove’s property—except when patronizing the hotel or restaurant, whatever those may become.

All of The Cove, in that sense, remains fine—its property rightly reserved for its customers. But the road and the beach belong to the public, and it is time we objected to the STOP sign.

As a publication, we believe in public access. Here is another example:

When we were told we had to pay for parking to reach Albion River Beach through the Albion Flats campground, we filed a complaint with the Coastal Commission. Others did the same. The Commission investigated and reached a compromise: one hour of free parking. I’m not sure such a time limit can legally stand, but the staff were pleasant, helpful, and even pointed me toward other options if I wanted to stay longer. That was several months ago, and for now the issue is settled. However, if Caltrans attempts to shut off all access to the Albion River and the beach beneath Albion Bridge when replacing the bridge, we will fight it—if necessary, in small claims court. We are strong believers in both private property and public access to public lands, especially the ocean

Back to the current situation

What’s needed is simple: remove the homemade signs and allow public access to the new lot that has already been built. No driveways would be blocked. No one would have to pass through a business or yard. Easy.

I am a Native Californian, a son of the Golden West. Public access for all is one of the things I love most about this state. Here, no one can block the public’s right to reach the beaches. Yes, there is a history of attempts to do so, and I’ve heard plenty more—though for now I’ll let those pass as rumor.pass as rumors.

At the Mendocino Cove open house, I heard two people refer to it as the “private beach.” I’m certain that was a misunderstanding. Just look at what has been built—parking, trails, and pathways—so that everyone can come and walk to the shore.

The owners purchased the property in 2020 for $2.998 million.

The Mendocino Cove owners also operate Mendocino Grove, a glamping retreat just south of town on the east side of the highway. The Grove has been a welcome addition to our community, with its owners showing generosity toward the arts and the wider Mendocino coast. We wish them well and thank them for bringing another Fort Bragg–appropriate hotel to market. In summer, when lodging is scarce, their investment makes a real difference. Their investment matters.

Although the owners of The Grove and The Cove at Mendocino live on Ocean Drive, they were not among the people I encountered on the road, nor were they involved in any of my three incidents. Others who described being harassed also did not point to the Cove owners.

We already have several nice but affordable gems, such as the Emerald Dolphin, Harbor Lite Lodge, the Beachcomber, and its sister inn north of town. A few truly upscale options exist, like Noyo Harbor Inn, alongside a range of economy inns. Yet some of these establishments are not a credit to the town overall. We hope that one or more could eventually be replaced with the badly needed workforce housing our community deserves.

Each of these places contributes to the mosaic of coastal hospitality.

Here’s the truth: hotels, restaurants, and glamping retreats thrive because of what makes Mendocino County extraordinary—open access to the land and sea. Public trails, public beaches, public bluffs. Without them, the coast becomes gated, the view narrowed, the spirit diminished.

So let this be our call: celebrate the new hotel, applaud the generosity, but never forget that the Golden West was built on the promise that the shore belongs to everyone. Public access is not a nuisance—it is the lifeblood of our community. And when the signs come down and the trail is opened, we will proclaim it without hesitation: Mendocino has gained not just another fine place to stay, but a renewed covenant with the ocean itself. The tide bears witness, the bluffs echo the truth: the coast is, and always will be, for us all.