No, It’s Not Just a Tax: Albion’s $600 Fire Measure Could Save Lives -Would Guarantee Two Responders Per Call-and Lower Your Insurance Premiums

An informal group of elders from Albion and Little River has proposed a $600 annual property tax to fund the local fire department. At two recent meetings, residents discussed in detail how the measure could ease the burden on overworked staff, replace aging equipment, and potentially lower fire insurance rates.

The big meeting is tonight—Wednesday at 6 p.m.—at the Whitesboro Grange. There’s no Wi-Fi at the Grange, so no Zoom option. Organizers say months have gone into drafting the proposal, and about $3,000 is needed to place it on the ballot. Only 150 signatures are required. The plan may evolve with community input, but here’s what’s on the table now:

Breaking Down the $600 Fire Tax: What’s Funded, What’s Not

The proposed funding would cover two full-time firefighters and upgrades to aging equipment—investments organizers say could eventually lower fire insurance costs enough to offset the tax hike. If passed, the measure would ensure at least two responders at every fire call. However, the tax would not address the equally urgent water infrastructure issues—a critical challenge for the fire department and for everything else in Mendocino’s most eclectic community (and one of the last with a measurable population of non-conformists).

We also encourage readers to review our related story outlining key recommendations.

The conversation has begun: read the first letter to the editor weighing in on the proposal..

We attended the first meeting about the proposed tax that a local citizens’ group hopes to place on the November 2026 ballot. We listened, followed up with more conversations, logged miles taking photos, and immersed ourselves in the layered history of Mendocino’s Deep End.

One of my favorite Albion fun facts? The town’s eccentricity, non-conformity, and artistic streak didn’t begin with the Albion Nation, the Lesbian Back-to-the-Land movement, or the hippie communes. Those were just the latest chapters in a much older story. The original Finnish settlers brought with them a fierce belief in freedom from conformity and government interference, communal living—and yes, hot tubs. Albion’s wacky, wonderful culture has deep roots.

For all its hot tubs and cool vibes, Albion still grapples with a stubborn water problem and limited road access. Add Little River to the mix, home to The Woods—a sprawling senior community nestled in the middle of it—and you’ve got two distinct places facing eerily similar challenges. Both suffer from major water infrastructure issues and dangerously few routes in or out, especially in the event of a wildfire—the Coast’s most likely large-scale natural disaster, aside from the more frequent torment of winter’s “atmospheric rivers,” which seem determined to test us all.

“I can tell you that in just the past few weeks, our chief has responded alone—in the middle of the night—to medical emergencies and traffic accidents,” said Sheila Klopper, who led the first meeting of the citizens’ group behind the bond proposal. “He’s one person, and he’s an EMT.”

“Are we really okay with just one person showing up?” Klopper asked. “We don’t think that’s acceptable—and it’s time to change it. If it’s not the chief responding alone, it’s Nick, one of our longtime firefighters, out there by himself.”

The tax would pay for two people to respond to every call.

Everyone—including critics of the proposal—agrees that the Albion–Little River Fire Department is essential to both communities’ survival and future. Most also acknowledge that the current assessment of $75–$150 per property isn’t enough. The annual barbecue remains a beloved tradition, and many pitch in where they can—but volunteers and brisket alone won’t keep the department running.

So why did voters reject the fire department’s last attempt at a property tax increase? Technically, they didn’t. A majority approved it—but the measure needed a two-thirds supermajority to pass. This time, organizers say only a simple majority is required. The difference? The proposal is being brought forward by a citizens’ group, not a government agency. Because it’s not a government entity asking for funds, the threshold is lower—or so we’ve all been told.

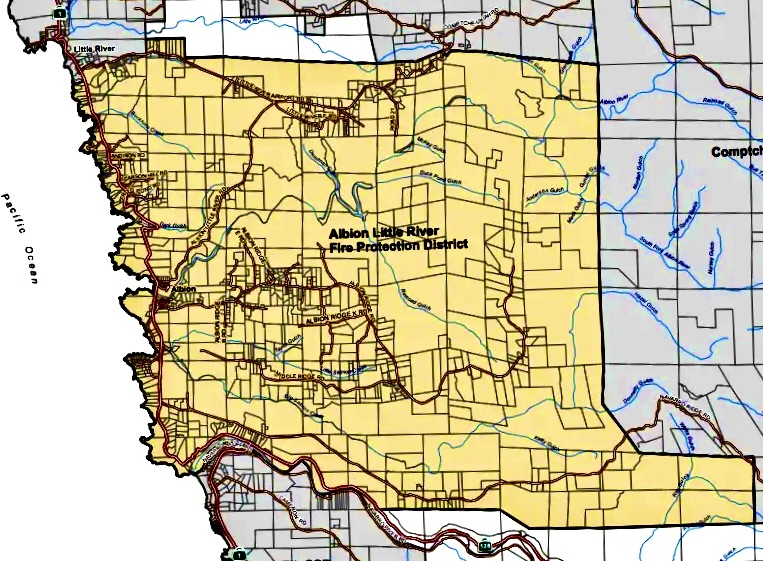

The Albion–Little River Fire Protection District operates five stations across 26 square miles of rugged terrain. The response area includes three spectacular ridges dotted with properties that are hard to serve—and sometimes hard to find. From secluded mansions fit for the “rich and intentionally not famous” to cozy, artistic Hippie Hollows, the homes here often come with confusing addresses, narrow roads, and forks that would baffle any outsider. Don’t count on Google Maps. And don’t count on cell service either. (Spoken from many firsthand misadventures by one often-lost Fort Bragger.)

If passed, this would be the first fire tax increase since 2014. The Albion–Little River Fire Protection District was formed in 1962, with its board presenting an annual budget for the all-volunteer departments—funded mostly by donations. A $40 tax was approved in 2002 and raised to $75 in 2014, though reports suggest many property owners actually paid closer to $150. We’re still seeking clarification on that point.

The current proposal closely mirrors 2024’s Measure S, which failed to reach the required two-thirds majority on the November ballot. Measure S proposed a $600 annual tax per residential parcel (land plus home), with a 2% annual increase. Commercial parcels were assessed differently—and notably, some were left out entirely. Organizers say this time, commercial properties will be included.

Measure S received 57% approval—587 yes votes to 437 no—but fell short of the supermajority threshold. Had it passed, it was projected to generate $668,000 annually for the fire district. It’s not yet clear how much revenue the new plan would bring in.

Chief Michael Rees said the department has about two dozen volunteers, but most work out of town.

“The volunteer model is not really sustainable for us as it has been in the past. And you know, that’s for a number of reasons. The main reason is the majority of our volunteers, which we have a pretty strong roster. We have 25 volunteers on the roster, and the main reason is, most of them work out of district. And it’s not just during the week, it’s on the weekends. So you know, Fire Capt. Nick Schwartz is one of the exceptions who lives and works in the district, mostly along with myself, but we are averaging over the last three months, our average turnout for a call is basically two and a half to three responders.”

Rees noted that today’s training requirements are tough to meet—especially for volunteers working without pay.

“The real kicker is personnel like we need to figure out a way to help our firefighters out, to compensate them for their time. Because it’s not only just running the calls they’re expected to train up to. A basic firefighter has to do anywhere from 250 to 350 hours of training just to be a firefighter. Then on top of that, if you’re going to be an EMT, that’s another 200 hours, depending where you do it. That’s our bare minimum. That’s what you got to be to even go out the door now, and we got to have maybe some sort of incident to get that training. When that training is not locally available, you have to go out of county or over the hill or out of county to get that training. So that’s kind of a nutshell what our needs are. I mean, if you add it all up on top of our current budget. Right now, the things that are not being funded, there’s about 1.4 million worth of needs. And it’s not wishes, like I hear that a lot too, wish list. They’re not wishes, they’re needs. It’s equipment. It’s vital equipment to keep us moving.”

“You’re hitting it hard, you’re really out there doing it—and it’s clear you need more people,” said Little River resident Ed Dowling. He asked which challenge was greater: the shortage of staff or the aging equipment.

Rees emphasized that recruiting more personnel is the department’s most urgent need.

“We can get at least one truck and water tender to go. And as thin as we are, we have a really tough time getting people to cover while we are out.”

Capt. Schwartz gave a rundown of how professionalism has dramatically increased over his two decades of service with Cal Fire, Anderson Valley, ALRFD, and—he noted—at least one other department.

“When I started Cal Fire and the local departments, we would get into almost brawls during trainings because we couldn’t work together, we couldn’t figure things out. People would show up at a call drunk. I mean, it was a wreck. The equipment was outdated. It wasn’t safe. The training standards didn’t really exist at all. I got given a type four fire apparatus, I think, a week into my tenure as a firefighter, and it lived in my front yard for three years. They just gave me a fire engine and said, take it home and then just show up. We can’t do that anymore. It’s a way higher standard, and we’re leading into the model of becoming semi professional or true professional firefighters. We want to show up to your homes and be able to save your lives and hand you off to the best care possible. And in order to do that, we need to be available. We need to show up in a timely manner, meaning getting to an engine that starts to jump or hook up to a booster thing. We have to be able to show up and then know what we’re doing and have the equipment to do it. My owner’s insurance got canceled three times in the last two years, and it went up from $1,700 a year to almost $ 10,000 that means I have to work a lot more,” Schwartz said.

There was considerable discussion about how increased funding for the fire department could potentially lead to lower fire insurance rates for Albion residents. While we struggled to clearly express that part of the equation, insurance agent Ray Alarcon reached out after reading our first story to help clarify.

“Their ISO rating was downgraded about 3-4 years ago which caused an increase in most premiums. That savings could help offset the struggle of some to pay for the extra assessment.”

Indeed, the alarming rise in wildfire intensity across California demands a far larger firefighting force—regardless of whether the state experiences a mild summer and fall season, as it did in 2025.

Of Mendocino County’s 22 fire districts, Chief Rees estimated that roughly half have paid staff. Mendocino’s Volunteer Fire Department currently has an unpaid chief—a situation Rees said will likely change with succession. The current chief serves without pay because he’s willing to and owns a successful business.

Rees noted that Anderson Valley and Hopland are among the districts with paid personnel. Nearby Elk, which had 110 calls last year, and Comptche, with around 70, both operate without paid staff. By comparison, Albion logged 314 calls—more than triple Elk’s volume.

Capt. Laurie Starr, a trained EMT who also works regularly in the emergency room locally, explained that today’s demand for highly qualified medical responders makes it difficult to recruit people like her—already trained and experienced—to complete the additional certifications required to respond in 2025.

“The majority of our calls are medical calls. Everybody in the community from a lift assist because they fell in the shower to minor and major traffic collisions, people need help from a person who has been properly trained. We are going to be the first people who come to help you. And so it’s really important for us to represent our fire department with all the education skills and training. When you call 911, you’re expecting the same type of help that shows up as in the city. You don’t expect your fire department to send somebody who is going to be like, Hey, so what’s going on? You have an injury that’s cool? Well, the ambulance is coming. I’ll just wave them down, you know. You expect more than that now. You expect us to help you in the same way that a fire department in a big city or the ambulance in a big city would. And so we have to have the training, we have to have the mindset, we have to have the ability to rest and eat well, to support ourselves, our families as well as the community. And if we don’t have those resources to provide that on a longer term basis then eventually we’re not going to be able to come. It’s just as simple as that, if we don’t have these sorts of resources available, it’s going to become more and more difficult for us to come.”

The equipment rundown revealed that the fire trucks carry only enough water for a few minutes of active firefighting. Many homes in the district lack reliable water hookups, making response even more challenging.

Schwartz and Rees spoke at length about the economic shifts in Albion, noting that with fewer local jobs than ever, most volunteers are commuting out of town for work—making consistent staffing a challenge.

“Michael has brought this fire department up to a completely professional standard,” Schwartz said. “I’ve seen a lot of chiefs and a lot of departments, and what Michael’s done here is remarkable. Thanks to his vision—and a new engine—we’re now able to operate at a contemporary standard. That hasn’t been the case in Albion for a long time.”

He described a recent Strike Team deployment to a nearly 140,000-acre wildfire in Central California, where 5,000 personnel were on the ground. “Albion stood shoulder to shoulder with professional, paid departments. We had a rig that passed inspection—something we haven’t always been able to say.”

Here is the video of the first meeting. Check it out!

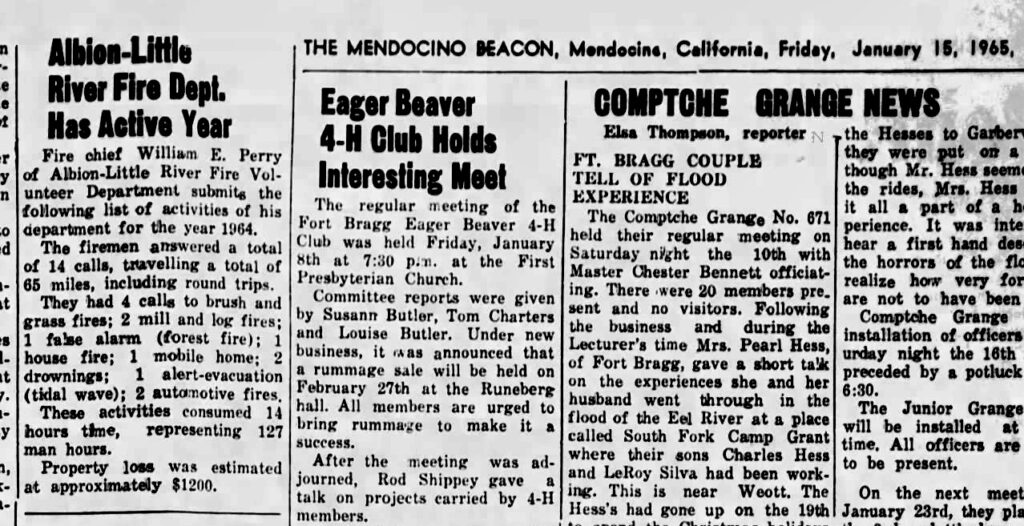

In 1965, the Albion–Little River Fire Department logged just 14 calls. Last year? 314.

Holy smoking pampas grass, Batman—how is that even possible?

A major rise in call volume comes from medical emergencies involving elderly residents, especially falls. Some are excruciating and require immediate transport to the ER; others call for a calm, medically trained firefighter who can assess and assist on scene. Another steady increase has come from traffic-related incidents, driven by the exponential growth in road use. To help offset costs, the department now bills insurance companies when responding to non-local individuals.

The committee behind the proposal is pictured at left.

Supervisor Ted Williams said he’s reviewed how funds have been spent since stepping down as fire chief, and believes the purchases have been sound—not excessive. He acknowledged that some residents want more detailed information but haven’t received it, noting that volunteer staff may not have the capacity to produce the kind of reports people expect.

Williams encouraged district residents to attend trainings, see the equipment firsthand, and ask questions directly of the crew.tions of the staff.

As the district braces for another year of unpredictable emergencies, the question isn’t whether the fire department will be needed—it’s when. “If someone knows they’re going to call 9-1-1 this next year, they’re going to be happy to spend that $600,” one resident said. “If they go the year without needing services, it’s going to feel like a sting—like they didn’t have it in their budget. It’s like buying insurance.”

And like insurance, it’s not just about you. It’s about your neighbor with a broken hip, the tourist who veers off Highway 1, the ridge-top home with no water hookup and a chimney fire at midnight.

One way to help right now? Sign up for one of Capt. Laurie Starr’s CPR classes. Learn the skills. Meet the crew. See the gear. And remember: this isn’t just a fire department—it’s a lifeline, built by neighbors, for neighbors.